by Sarah Firisen

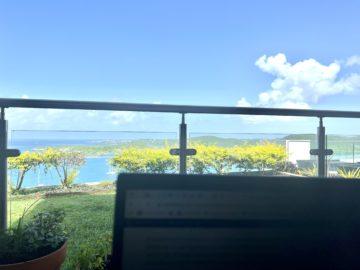

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.

I recently started a new job. The process of looking and interviewing for this job was unlike any other I’ve been through because I now live on the Caribbean island of Grenada. I moved here during the height of the pandemic when everyone was working from home. When I told my plans to the company I was working for then, their only comment was that I needed to stay domiciled in the US, which I have. But now that we’ve all gone back to some kind of post-COVID normalcy (even if variants are still coming at us hard and fast), I wasn’t sure how to approach a new company with my slightly unusual living situation. My initial thoughts were that I get through a first interview before bringing it up, but that seemed not only disingenuous but also pointless; they were going to have a problem with it, or they weren’t. Putting off the reveal was just a waste of everyone’s time. And so, I mostly led with this news. Amazingly, no one cared.

I work in sales in the technology start-up space, and I realize that this niche of corporate life is perhaps not representative. However, it’s still interesting that not one of the companies I interviewed with even took a beat over my location. The company I finally accepted an offer from, BusinessOptix, is split between the UK and Kansas in the US. The client I’ll be managing is mainly in New York City, so as long as I was in the same time zone as them and could get back to NYC quickly, it wasn’t an issue.

In a couple of weeks, I’m running a workshop in New York where I’ll meet some of my new colleagues for the first time. This is a meeting I’ve been pushing for, because, as much as I am a huge advocate (and beneficiary) of remote work, there are also times when you just need to be in the same room as people sitting across a table for a bunch of hours, then breaking bread and drinking some wine together. I’m far from the only person trying to find that perfect balance of in-person and virtual. Read more »

In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine.

In the early 1990’s I was a visiting fellow at St Catherine’s College and an academic visitor at Nuffield College in Oxford. At Nuffield College at that time two friends from my Cambridge student days were Fellows, Jim Mirrlees and Christopher Bliss. (I think Jim was mostly away during my visit, and graciously asked me to use his large office at Nuffield). The other person I used to see there off and on was Tony Atkinson who became the Warden of Nuffield shortly afterward. I knew Tony since our student days in Cambridge. Like me he also moved from one Cambridge to the other, to MIT, roughly around the same time. Both of us were heavily influenced by our teacher James Meade, though Tony never did a Ph.D. (as used to be the old British tradition—neither James Meade nor Joan Robinson had a Ph.D.) Tony did not follow Meade in the latter’s work on international trade, as I did, but in other respects he broadly followed on the footsteps of Meade, apart from sharing Meade’s personal characteristics of modesty, decency and a positive vision of the future. Tony was certainly among the best economists of my generation, with pioneering work on inequality, poverty, public policies, redistributive taxation, and welfare. He was also an advocate of Universal Basic Income. I had co-authored a chapter for the Handbook of Income Distribution that he co-edited with François Bourguignon, a French development economist friend of mine. Published by Thunder Bay Press, The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics: 1963-1970 offers an attractive, if strangely incomplete, collection of the lyrics that John, Paul, George, and (very rarely) Ringo produced during their 1960s heyday. The brevity of the Beatles’ career—seven short years from “Please Please Me” to “The Long and Winding Road”—remains the most mystifying element of the band, of how so much music poured out of the band in a remarkably brief amount of time. The Beatles Illustrated does not offer any answers or provide any new insight on the Fab Four’s magic—the commentary is limited to Steve Turner’s one-page introduction—but instead captures the bulk of the Beatles’ lyrics alongside some great photos of the band and illustrations that nicely compliment the songs.

Published by Thunder Bay Press, The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics: 1963-1970 offers an attractive, if strangely incomplete, collection of the lyrics that John, Paul, George, and (very rarely) Ringo produced during their 1960s heyday. The brevity of the Beatles’ career—seven short years from “Please Please Me” to “The Long and Winding Road”—remains the most mystifying element of the band, of how so much music poured out of the band in a remarkably brief amount of time. The Beatles Illustrated does not offer any answers or provide any new insight on the Fab Four’s magic—the commentary is limited to Steve Turner’s one-page introduction—but instead captures the bulk of the Beatles’ lyrics alongside some great photos of the band and illustrations that nicely compliment the songs. With its recent

With its recent  Anita’s case was far from unique. According to hospital records, the women’s ward in Herat saw 900 such cases that April. In 2021, the facility recorded 12,678 cases, up from 10,800 cases in 2020.

Anita’s case was far from unique. According to hospital records, the women’s ward in Herat saw 900 such cases that April. In 2021, the facility recorded 12,678 cases, up from 10,800 cases in 2020. Suppose that I am polyamorous and that my mother disapproves. She tolerates my love life but thinks it’s wrong that I have not one partner but two. What her half-accepting, half-critical attitude reveals is a duality at the heart of toleration, an ambivalence that is beautifully captured by the British philosopher

Suppose that I am polyamorous and that my mother disapproves. She tolerates my love life but thinks it’s wrong that I have not one partner but two. What her half-accepting, half-critical attitude reveals is a duality at the heart of toleration, an ambivalence that is beautifully captured by the British philosopher  t was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that

t was on a train journey, from Richmond to Waterloo, that  If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly

If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly  Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson):

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson): The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of

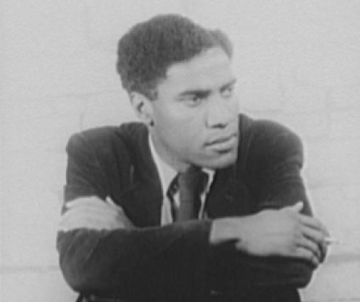

The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of  The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives.

The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives. Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the

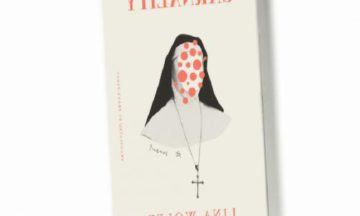

Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the  “Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.

“Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.