by Brooks Riley

by Brooks Riley

by Rebecca Baumgartner

In T.H. White’s masterpiece The Once and Future King, Merlyn’s recommendation for “see[ing] the world around you devastated by evil lunatics” is to learn something:

“There is only one thing for it then – to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting.”

This summer, as I’ve watched my own country being devastated by evil lunatics, I’ve tried to take this advice to heart. Under Merlyn’s tutelage, the future King Arthur learned about his world by taking the form of various animals and seeing how they lived. We have to make do with a different form of sorcery – one that, rather than educating us about others, merely shows us a reflection of ourselves fractally repeated; one that keeps us sad and angry and has proven to be far less helpful in dealing with evil lunatics than one would hope: the internet.

When the Supreme Court released its now-infamous round of rulings towards the end of June – in a whirlwind week that felt like the answer to the question, “What if America were a monarchy?” – I obviously turned to the internet to find out what I could do.

But, as I quickly discovered, it’s hard to formulate a series of Google search terms that could possibly lead to anything helpful right now. The fact that I tried to do so anyway is a telling demonstration of how our capacity for action is mediated and diluted by the internet. Read more »

by Ada Bronowski

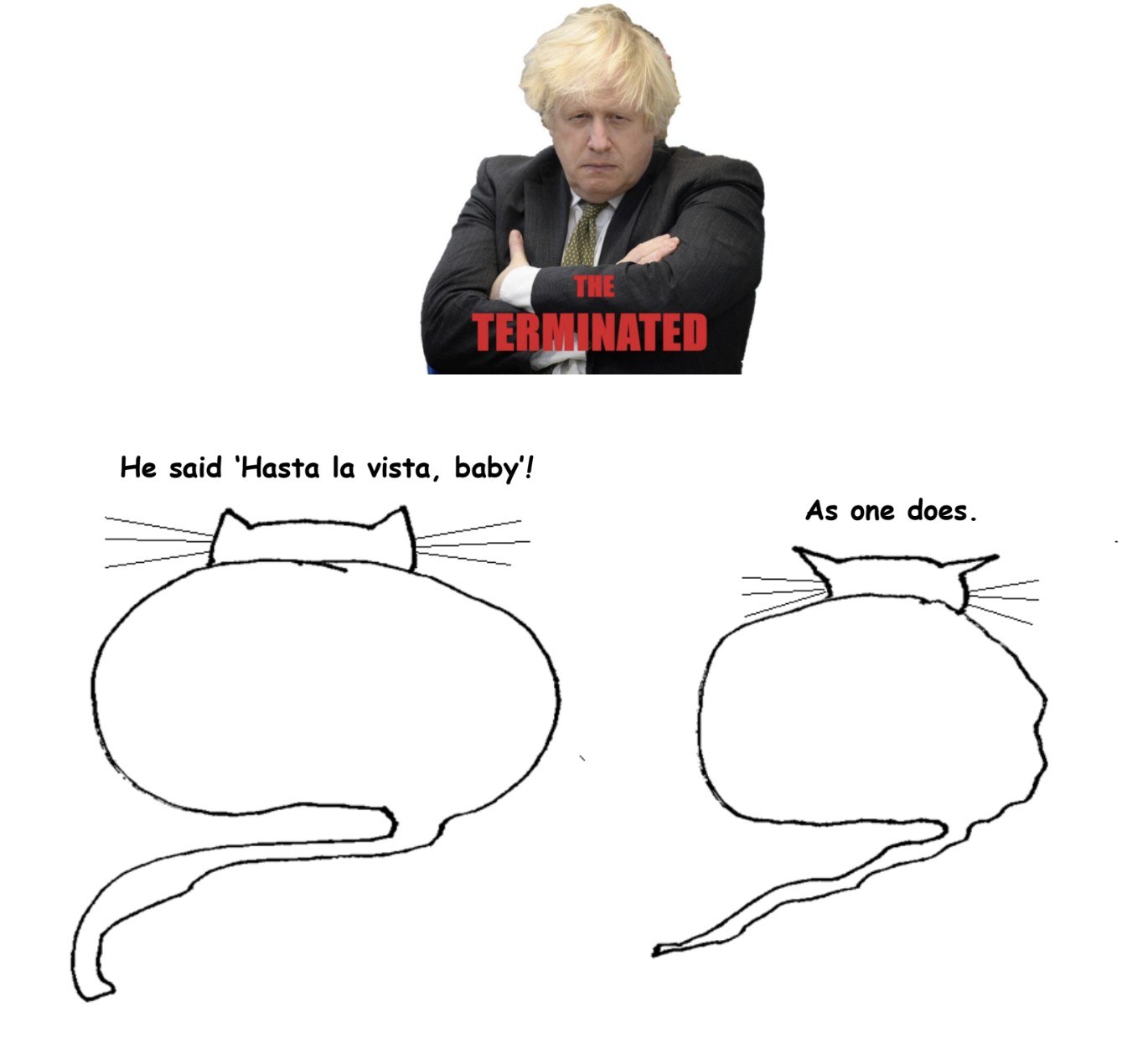

![]() More than an age of anxiety or anger, of indignation or self-righteousness, we live in an age of the constant high. We need not consume drugs or get inebriated to be met on a daily basis with sights and behaviours to which the only reasonable reaction is an alternation between ‘wow!’ and ‘oh my god…!’ From the still-not-yet-former British prime minister saluting the oldest of the modern parliaments with a deep-felt ‘Hasta la vista baby!’, to newspaper frontpages, to twitter feeds, the most pervasive mode of communication in contemporary society is the exclamation. Social media experts and communication analysts of every stripe routinely provide us with statistics demonstrating the normalisation of the exclamation point as a sine qua non of everyday communication. It is the lack of one which legitimately arouses concern. The use of a full stop at the end of a sentence tends rather to indicate that something is not quite right. Whether you write a text saying: ‘I’m waiting.’, or whether you write: ‘I’m waiting!’, the recipient knows either to be worried they have annoyed you in the former case, or that all is fine in the latter case, though without then assuming any particular degree of excitement. Whether someone writes in an email or text: ‘That’s perfect.’ or ‘That’s perfect!’, you sense in the former case, that something is in fact not quite perfect, whereas in the latter case, you do not consider anything’s being either perfect or not. The exclamation point, rather than emphasise excitement, functions as a neutraliser, shifting the focus of a sentence away from its actual content. Read more »

More than an age of anxiety or anger, of indignation or self-righteousness, we live in an age of the constant high. We need not consume drugs or get inebriated to be met on a daily basis with sights and behaviours to which the only reasonable reaction is an alternation between ‘wow!’ and ‘oh my god…!’ From the still-not-yet-former British prime minister saluting the oldest of the modern parliaments with a deep-felt ‘Hasta la vista baby!’, to newspaper frontpages, to twitter feeds, the most pervasive mode of communication in contemporary society is the exclamation. Social media experts and communication analysts of every stripe routinely provide us with statistics demonstrating the normalisation of the exclamation point as a sine qua non of everyday communication. It is the lack of one which legitimately arouses concern. The use of a full stop at the end of a sentence tends rather to indicate that something is not quite right. Whether you write a text saying: ‘I’m waiting.’, or whether you write: ‘I’m waiting!’, the recipient knows either to be worried they have annoyed you in the former case, or that all is fine in the latter case, though without then assuming any particular degree of excitement. Whether someone writes in an email or text: ‘That’s perfect.’ or ‘That’s perfect!’, you sense in the former case, that something is in fact not quite perfect, whereas in the latter case, you do not consider anything’s being either perfect or not. The exclamation point, rather than emphasise excitement, functions as a neutraliser, shifting the focus of a sentence away from its actual content. Read more »

by Dick Edelstein

Ireland has produced a number of prominent scientists despite being a small nation, but if you ask an average citizen about John Stewart Bell, one of the top Irish scientists of all time, you are likely to draw a quizzical look. That is mainly because the area of Bell’s important contribution, quantum mechanics, is so difficult to grasp.

Robert Boyle, on the other hand, is well known throughout the land. Boyle’s Law describes the relationship between the pressure and volume of gas molecules in a closed chamber. Tourists visiting Dublin’s Trinity College to view the Book of Kells, a spectacularly illuminated medieval bible, also see a 17th Century bust of Boyle prominently displayed in the Long Room of the Trinity College Library.

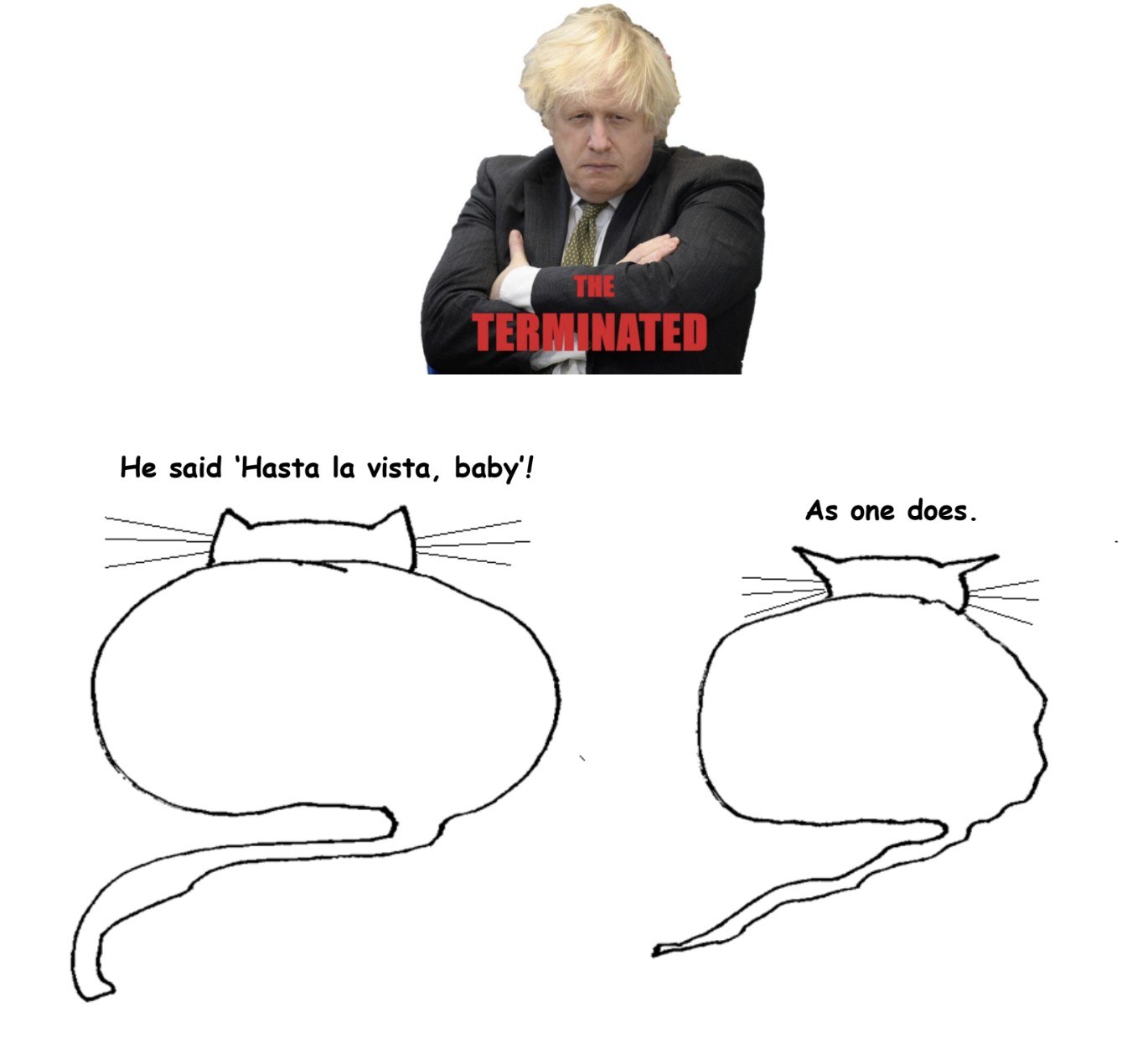

The public reputation of the 18th Century scientist and mathematician William Rowan Hamilton lies somewhere between that of these two figures. His name is fairly well known, and each year a prestigious guest lecture commemorating his work and career is given in the historic physics building in Trinity College. The importance of his work and exactly what he has accomplished in science and mathematics is less well known. As with Bell, this is partly because his most important discovery is not easy to grasp. In addition, his work was for a long time regarded as esoteric. In fact, it took over a century for his discovery of the mathematical concept of quaternions to have a significant application in technology. Read more »

by Derek Neal

“Paradiso” by Erlend Oye is a song I’ve heard many times in many different settings. This is largely a result of circumstance: it is one of the few songs I keep on my iPhone, and I return to it when I’m driving and my phone doesn’t have cellular service. Once upon a time I had an iPod loaded with an extensive music library, thousands and thousands of songs, maybe even up to and over 50 GB, although I suppose this number has steadily increased in direct relation to the time it’s been since I owned an iPod. Every generation has their version of this story—record collections, cassette collections, CD collections, MP3 collections. Perhaps my generation was the last to experience the phenomenon of collecting and curating a music library as an ordinary cultural experience and not as a conscious act of rebellion against streaming technology, which by its very nature precludes the idea of ownership, having or not having, and the decisions that lie therein.

“Paradiso” by Erlend Oye is a song I’ve heard many times in many different settings. This is largely a result of circumstance: it is one of the few songs I keep on my iPhone, and I return to it when I’m driving and my phone doesn’t have cellular service. Once upon a time I had an iPod loaded with an extensive music library, thousands and thousands of songs, maybe even up to and over 50 GB, although I suppose this number has steadily increased in direct relation to the time it’s been since I owned an iPod. Every generation has their version of this story—record collections, cassette collections, CD collections, MP3 collections. Perhaps my generation was the last to experience the phenomenon of collecting and curating a music library as an ordinary cultural experience and not as a conscious act of rebellion against streaming technology, which by its very nature precludes the idea of ownership, having or not having, and the decisions that lie therein.

I could be wrong: maybe kids today sit on the school bus and share their Spotify libraries with each other in the same way that we would hand over our iPods and await judgement. But without the need to own music to listen to it, to decide what’s in and what’s out, and when everyone has access to every song, there must naturally be less of an impulse to cultivate a library. In any case, I’ve often found myself in various locations where I can’t stream Spotify, or call up YouTube, or listen to a DJ mix on SoundCloud: for example, driving in a foreign country, or going to my family’s cottage where the reception is poor, or when I simply don’t have any data left on my phone. “Paradiso” is one of the songs that I’ve returned to in these moments, and it has wormed its way through my ears and into my brain, not from love or obsession, although I do of course enjoy the song, but from mere repetition and necessity. The song describes one of the eternal human dramas that everyone will be able to relate to at some point in their lives. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

In earlier decades on my way to or from India I’d often stop in London, and go to LSE and spend some time with my friends, including Nick Stern and Meghnad Desai (since then both of these people became Lords). Meghnad once invited me to a visit at the House of Lords, showed me around and took me to lunch there. Meghnad with his distinct Afro hairdo and all has always been a flamboyant character. He used to claim to be a Marxist economist. Rumor had it that he and his first wife (Gail, who I think was related to the wealthy Guinness Family) had a summer villa in south of France, where reportedly the only book on the shelf was Das Kapital. During the Vietnam War days he was active at the LSE protests against the War. I was told that my teacher Frank Hahn, who had moved from Cambridge to LSE by then, once suggested to Meghnad, in a characteristic Frank Hahn way, to publicly immolate himself in front of the LSE building in a spectacular anti-war protest gesture (around that time some Vietnamese monks immolating themselves in protest in Saigon had hit the headlines). Later Meghnad became one of the Thatcher-admiring (or –internalizing) Labor Party members. Now I hear in India he is a Modi-admirer. He is also the Chairman of the Meghnad Desai Academy of Economics he has founded in Mumbai. Read more »

Justin E. H. Smith in The New Statesman:

While the question of alien life is never far from our investigations of distant galactic structures, the device’s distinctive honeycomb structure seems emblematic of the organic complexity of our own planet, of what it has been capable of producing, and what it is capable of projecting out into space.

While the question of alien life is never far from our investigations of distant galactic structures, the device’s distinctive honeycomb structure seems emblematic of the organic complexity of our own planet, of what it has been capable of producing, and what it is capable of projecting out into space.

As usual with expensive astronomical projects, there are complaints about all the ways the money might have been better spent here on Earth. We are neglecting complex and fragile habitats, it is said, some of which we now risk losing through ecological crisis, yet instead we are seeking to discern the nature of objects so distant that they are unlikely to have any practical relevance for terrestrial life. This objection is reinforced by the fact that the Webb telescope was not conceived to deliver anything fundamentally different from what its predecessor, the Hubble, has been yielding since its launch in 1990 except a higher-quality version of the same – the Webb telescope has the power to detect distant objects up to 100 times fainter than anything Hubble can see.

What these complaints miss is that nothing could be more existentially urgent than knowing our place in the world, which means in part knowing the extent, the diversity, and the nature of the entities that make up the entire cosmos.

More here.

Gary Marcus in his Substack newsletter:

The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility – but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far.

The intuition that language might simply be memorized has some superficial plausibility – but only if you restrict your focus to simple concrete nouns like ball and bottle. A child looks at a bottle, mama says bottle, and child associates the word bottle with the concept BOTTLE. Some tiny fragment of language may be learned this way. But this simple learning by pointing-plus-naming idea, as intuitive as it is, doesn’t get you very far.

It doesn’t work all that well for abstract nouns (what do you point to when you are talking about the word justice?). It doesn’t work particularly well for sorting the fine detail of verbs [when mama points to a dog that is barking and says bark, does the word bark refer to the act of barking or the act of sitting or the act of breathing or the act of living? or to any of the other many things that might apply to the dog at that moment?

More here.

Christopher J. Ferguson in Quillette:

Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization.

Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization.

More here.

Verlyn Klinkenborg in Literary Hub:

Here, in short, is what I want to tell you.

Know what each sentence says,

What it doesn’t say,

And what it implies.

Of these, the hardest is knowing what each sentence actually says.

At first, it will help to make short sentences,

Short enough to feel the variations in length.

Leave space between them for the things that words can’t really say.

Pay attention to rhythm, first and last.

More here.

1-Philosophy

Never ask Why What,

Always ask What’s What.

Observe, connect, and do.

The great Winemaster is almost a

a magician to the bulk of his Tribe,

to his peers he is only accurate.

“He knows the grape so well,” they say,

“he turned into a vine.”

2-College Graduation Address

(1) Freak out.

(2) Come back.

(3) Bandage the wounded and feed

……however many you can.

(4) Never cheat.

3-College Oath

All persecutors

Shall be violated!

from Ring of Bone, Lew Welch Collected Poems, 1950-1971

Grey Fox Press, 1979

Bob Yirka in Phys.Org:

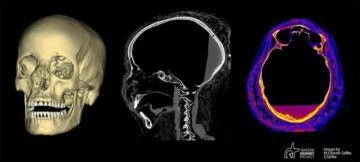

A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their webpage that a mummy in their collection that has come to be known as the Mysterious Lady may have had nasopharyngeal cancer. The mummy, which made headlines last year when researchers discovered she had been pregnant at the time of her death, was found in Thebes (now called Luxor) in Egypt sometime in the early part of the 19th century and was subsequently donated to the University of Warsaw in 1826. The sarcophagus holding the mummy was only recently opened for study.

A team of researchers with the Warsaw Mummy Project, has announced on their webpage that a mummy in their collection that has come to be known as the Mysterious Lady may have had nasopharyngeal cancer. The mummy, which made headlines last year when researchers discovered she had been pregnant at the time of her death, was found in Thebes (now called Luxor) in Egypt sometime in the early part of the 19th century and was subsequently donated to the University of Warsaw in 1826. The sarcophagus holding the mummy was only recently opened for study.

Russ Roberts in The New York Times:

In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin made a list of the expected pluses and minuses of marrying. On the left-hand side he tried to imagine what it would be like to be married (“constant companion,” “object to be beloved & played with — better than a dog anyhow”). On the right-hand side he tried to imagine what it would be like not to marry (“not forced to visit relatives & to bend in every trifle”).

In 1838, Charles Darwin faced a problem. Nearing his 30th birthday, he was trying to decide whether to marry — with the likelihood that children would be part of the package. To help make his decision, Darwin made a list of the expected pluses and minuses of marrying. On the left-hand side he tried to imagine what it would be like to be married (“constant companion,” “object to be beloved & played with — better than a dog anyhow”). On the right-hand side he tried to imagine what it would be like not to marry (“not forced to visit relatives & to bend in every trifle”).

Darwin was struggling with what I call a wild problem — a fork in the road of life where knowing which path is the right one isn’t obvious, where the day-to-day pleasure and pain from choosing one path over another are ultimately hidden from us and where those day-to-day pleasures and pains don’t fully capture what’s at stake.

More here.

Julie Kliegman at Bookforum:

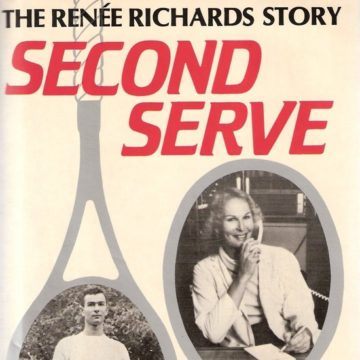

RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

RENÉE RICHARDS, eighty-seven, has admitted she has some regrets. Among them is that she never pitched for the New York Yankees, a job MLB scouts once seemed to think she had a real shot at.

Her contributions to the sports landscape, though, ended up being far greater than a few years in pinstripes. Had she played for the Yankees, she might never have had a sex change (her preferred term). Had she never had a sex change, she never would’ve had to fight tennis officials for a spot in the women’s draw of the 1977 US Open.

In Richards’s two autobiographies, Second Serve and No Way Renée, published in 1983 and 2007, respectively, she offers a glimpse into what it was like being a transsexual (also her term) in the 1970s—a time when trans people were met with derision, if they were acknowledged at all—even as it seems she’d rather be writing about almost anything else.

more here.

Abdulrazak Gurnah at The Guardian:

My earliest reading memory

Undoubtedly the Qur’an. Growing up in Zanzibar I started in chuoni, which is what we called Qur’an school, at the age of five and did not start government school until a year later, by which time I was certain to have been reading the short suras. Quite early on in government school, one of our class texts was a Kiswahili translation of Aesop’s Fables, with illustrations of the fox making a futile leap at the grapes and the hare lounging by the roadside as the tortoise came trundling by. I can still see those images.

My favourite book growing up

A Kiswahili translation of abridged selections from Alfu Leila u Leila (A Thousand and One Nights) in four slim volumes. It was there that I first read the story Kamar Zaman and Princess Badoura, which has stayed with me since.

more here.