Jim Davies in Nautilus:

Do we need artificial intelligence to tell us what’s right and wrong? The idea might strike you as repulsive. Many regard their morals, whatever the source, as central to who they are. This isn’t something to outsource to a machine. But everyone faces morally uncertain situations, and on occasion, we seek the input of others. We might turn to someone we think of as a moral authority, or imagine what they might do in a similar situation. We might also turn to structured ways of thinking—ethical theories—to help us resolve the problem. Perhaps an artificial intelligence could serve as the same sort of guide, if we were to trust it enough.

Do we need artificial intelligence to tell us what’s right and wrong? The idea might strike you as repulsive. Many regard their morals, whatever the source, as central to who they are. This isn’t something to outsource to a machine. But everyone faces morally uncertain situations, and on occasion, we seek the input of others. We might turn to someone we think of as a moral authority, or imagine what they might do in a similar situation. We might also turn to structured ways of thinking—ethical theories—to help us resolve the problem. Perhaps an artificial intelligence could serve as the same sort of guide, if we were to trust it enough.

Even if we don’t seek out an AI’s moral counsel, it’s just a fact now that more and more AIs have to make moral choices of their own. Or, at least, choices that have significant consequences for human welfare, such as sorting through resumes to narrow down a list of candidates for a job, or deciding whether to give someone a loan.1 It’s important to design AIs that make ethical judgments for this reason alone.

More here.

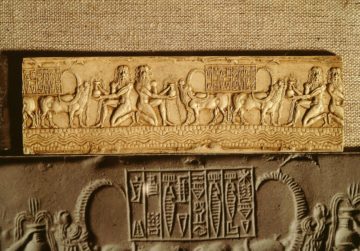

The missing earthworms were a sign. As archaeologist Harvey Weiss and his colleagues excavated a site in northeast Syria, they found a buried layer of wind-blown silt so barren there was hardly any evidence of earthworms at work during that ancient era. Something drastic had happened thousands of years ago — something that choked the land with dust for decades, leaving a blanket of soil too inhospitable even for earthworms.

The missing earthworms were a sign. As archaeologist Harvey Weiss and his colleagues excavated a site in northeast Syria, they found a buried layer of wind-blown silt so barren there was hardly any evidence of earthworms at work during that ancient era. Something drastic had happened thousands of years ago — something that choked the land with dust for decades, leaving a blanket of soil too inhospitable even for earthworms. I was watching Oneohtrix Point Never in the related project of trying to figure out just what the heck exactly it is about The Weeknd, who released his most recent album, Dawn FM, a couple of weeks ago, and I have never quite been able to understand why I am both attracted to and repelled by everything that is The Weeknd. I say repelled because there is a kind of loosely held emptiness, a brazen cynicism and pure Pop indifference to the music of The Weeknd that often makes me feel frustrated both with The Weeknd (why do you have to be so glib?!?!) and then in some related way with myself and then also with nearly everything. But then when I listen to The Weeknd for a little longer I realize that he is also frustrated with himself, and by extension with me and also very much with more or less everything. His music is the music of that. And then somehow it is also at the same time the utmost in listenable and cherry-flavored fun-all-the-way-down meaningless Pop.

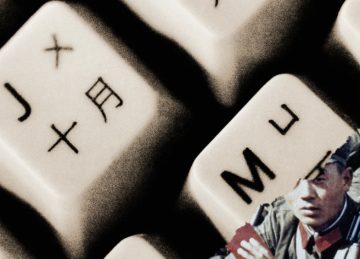

I was watching Oneohtrix Point Never in the related project of trying to figure out just what the heck exactly it is about The Weeknd, who released his most recent album, Dawn FM, a couple of weeks ago, and I have never quite been able to understand why I am both attracted to and repelled by everything that is The Weeknd. I say repelled because there is a kind of loosely held emptiness, a brazen cynicism and pure Pop indifference to the music of The Weeknd that often makes me feel frustrated both with The Weeknd (why do you have to be so glib?!?!) and then in some related way with myself and then also with nearly everything. But then when I listen to The Weeknd for a little longer I realize that he is also frustrated with himself, and by extension with me and also very much with more or less everything. His music is the music of that. And then somehow it is also at the same time the utmost in listenable and cherry-flavored fun-all-the-way-down meaningless Pop. Quiet, cautious, and insistent, Zhi was also highly qualified. He earned a PhD in physics from Leipzig University but declined a job offer in the United States in order to return to China. He taught at two Chinese universities and later helped to devise China’s landmark 12-year Plan for the Development of Science and Technology of 1956. It was a hopeful time for scientists and technicians who were deemed useful for their contributing roles in a state-guided socialist economy.

Quiet, cautious, and insistent, Zhi was also highly qualified. He earned a PhD in physics from Leipzig University but declined a job offer in the United States in order to return to China. He taught at two Chinese universities and later helped to devise China’s landmark 12-year Plan for the Development of Science and Technology of 1956. It was a hopeful time for scientists and technicians who were deemed useful for their contributing roles in a state-guided socialist economy. A passage in Walt Whitman’s seminal 1855 work, Leaves of Grass, reads, “And do not call the tortoise unworthy because she is not / something else, / And the mocking bird in the swamp never studied the / gamut, yet trills pretty well to me.” Another reads, “For me the man that is proud and feels how it stings to be / slighted, / For me the sweetheart and the old maid…for me / mothers and the mothers of mothers, / For me lips that have smiled, eyes that have shed tears, / For me children and the begetters of children.”

A passage in Walt Whitman’s seminal 1855 work, Leaves of Grass, reads, “And do not call the tortoise unworthy because she is not / something else, / And the mocking bird in the swamp never studied the / gamut, yet trills pretty well to me.” Another reads, “For me the man that is proud and feels how it stings to be / slighted, / For me the sweetheart and the old maid…for me / mothers and the mothers of mothers, / For me lips that have smiled, eyes that have shed tears, / For me children and the begetters of children.” The euro’s primary purpose was to facilitate integration by eliminating the cost of currency conversions and, more importantly, the risk of destabilizing devaluations. Europeans were promised that it would encourage cross-border trade. Living standards would converge. The business cycle would be dampened. It would bring greater price stability. And intra-eurozone investment would yield faster productivity growth overall and convergent growth between member countries. In short, the euro would underpin the benign Germanization of Europe.

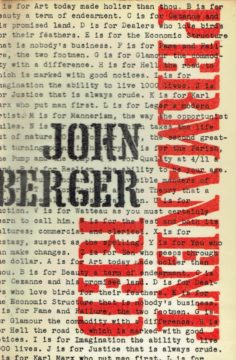

The euro’s primary purpose was to facilitate integration by eliminating the cost of currency conversions and, more importantly, the risk of destabilizing devaluations. Europeans were promised that it would encourage cross-border trade. Living standards would converge. The business cycle would be dampened. It would bring greater price stability. And intra-eurozone investment would yield faster productivity growth overall and convergent growth between member countries. In short, the euro would underpin the benign Germanization of Europe. What all this comes down to, then, is that Berger accepts a priori a militant and often staggeringly vulgarized brand of Marxism from which all his judgments about art derive, in language anyway. (Since we are never allowed to view the actual procedure by which Berger judges that one painting is “subjective” or “decadent” and another not—this would involve defining Marxist terminology in visual terms—we can say no more than this.) Furthermore, when Berger finds himself in a position that, even to the layman, is pretty obviously untenable, he is prepared to deny its apparent meaning and then reintroduce the untenable notion through the loaded use of supposedly neutral or descriptive words—such as “improvement” in the above example. My fundamental objection is not that Berger begins from a position of accepting Marxist theory. In the world we live in more and more critics of art may be expected to start from similar political premises. But what is imperative is that the critic define his terms; that he show with sensitivity and logical rigor the usefulness and, if possible, the necessity of employing Marxist concepts and terminology. Unless he can do this his judgments will reveal nothing more than the strength of his bias and the slovenliness of his mind: they can say nothing about the works of art in question.

What all this comes down to, then, is that Berger accepts a priori a militant and often staggeringly vulgarized brand of Marxism from which all his judgments about art derive, in language anyway. (Since we are never allowed to view the actual procedure by which Berger judges that one painting is “subjective” or “decadent” and another not—this would involve defining Marxist terminology in visual terms—we can say no more than this.) Furthermore, when Berger finds himself in a position that, even to the layman, is pretty obviously untenable, he is prepared to deny its apparent meaning and then reintroduce the untenable notion through the loaded use of supposedly neutral or descriptive words—such as “improvement” in the above example. My fundamental objection is not that Berger begins from a position of accepting Marxist theory. In the world we live in more and more critics of art may be expected to start from similar political premises. But what is imperative is that the critic define his terms; that he show with sensitivity and logical rigor the usefulness and, if possible, the necessity of employing Marxist concepts and terminology. Unless he can do this his judgments will reveal nothing more than the strength of his bias and the slovenliness of his mind: they can say nothing about the works of art in question. Not long after we began dating, my now wife, Christine, and I started making up stories about the child we might have.

Not long after we began dating, my now wife, Christine, and I started making up stories about the child we might have. Smashing the patriarchy in the human world has been easier said than done. But last year, a 9-year-old female Japanese macaque in a reserve in southern Japan showed humans how it’s done by violently overthrowing the alpha male of her troop to become its first female leader in the reserve’s 70-year history. The macaque, named Yakei, presides over a troop of 677 monkeys in Takasakiyama Natural Zoological Garden, which was established as a reserve for monkeys in 1952. There are two troops on the island reserve, and they spend most of their time roaming the forested mountain at its center. They also make daily visits to a park at the base of the mountain, where the staff provides food. Since the reserve opened, its staff has kept tabs on the romantic and political struggles of its simian residents.

Smashing the patriarchy in the human world has been easier said than done. But last year, a 9-year-old female Japanese macaque in a reserve in southern Japan showed humans how it’s done by violently overthrowing the alpha male of her troop to become its first female leader in the reserve’s 70-year history. The macaque, named Yakei, presides over a troop of 677 monkeys in Takasakiyama Natural Zoological Garden, which was established as a reserve for monkeys in 1952. There are two troops on the island reserve, and they spend most of their time roaming the forested mountain at its center. They also make daily visits to a park at the base of the mountain, where the staff provides food. Since the reserve opened, its staff has kept tabs on the romantic and political struggles of its simian residents.

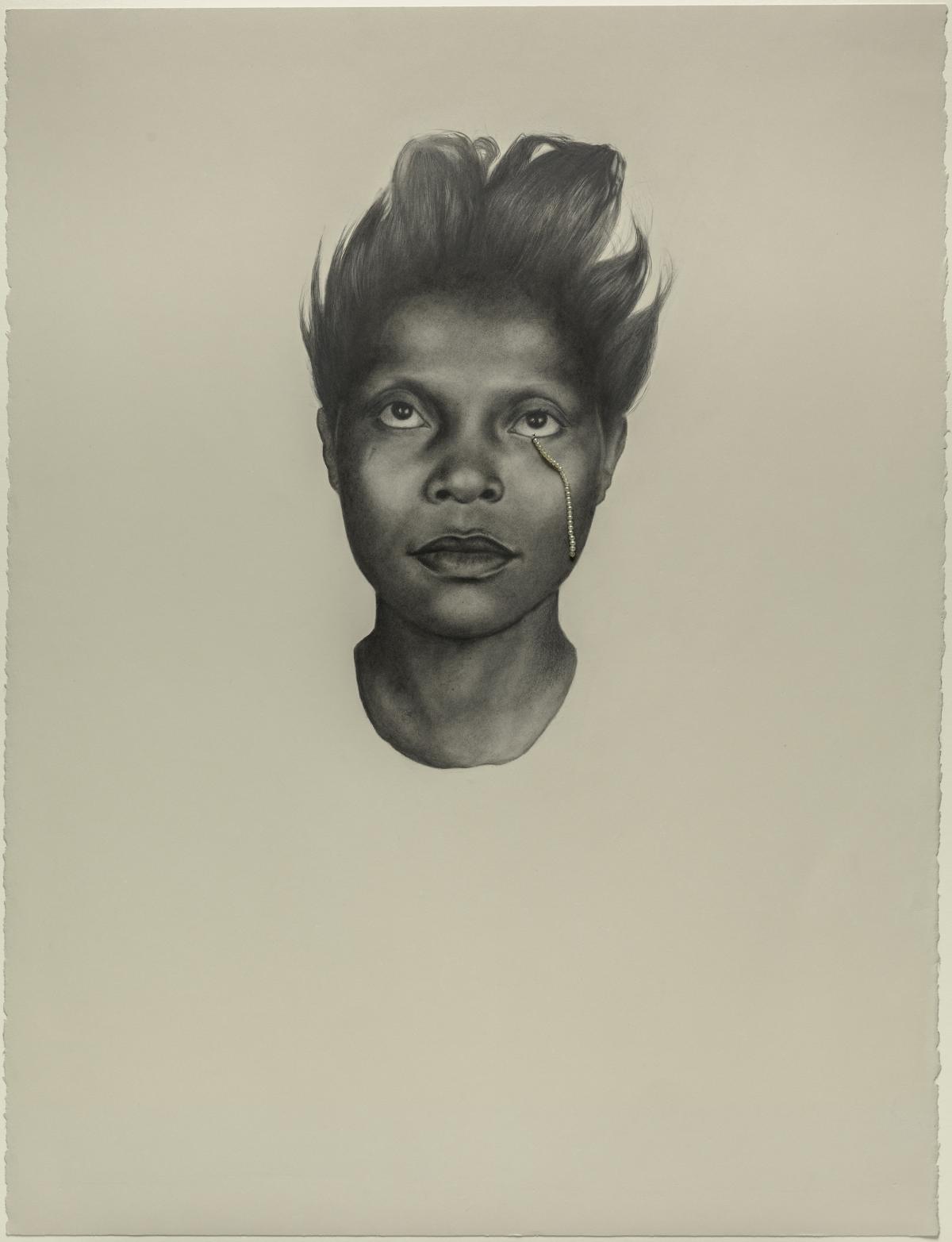

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011.

Whitfield Lovell. Kin XLV (Das Lied von der Erde), 2011. Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies.

Not long ago, having steeled myself for the read-through of yet another dry but informative assessment of the body’s immune response to Covid 19 and her variant offspring, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself being dragged into a barbaric tale of murder and mayhem, full of gory details and dire strategies. We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.