Lawrence M. Krauss in Quillette:

Recent White House initiatives suggest that addressing climate change has risen to the policy forefront of government at the presidential level for the first time in US history. Last week President Biden convened an online international meeting of heads of state on the issue and committed the US to a dramatic effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level of 50 percent of emissions in 2005 by the year 2030, which will require unprecedented action and cooperation between government and major industries.

Recent White House initiatives suggest that addressing climate change has risen to the policy forefront of government at the presidential level for the first time in US history. Last week President Biden convened an online international meeting of heads of state on the issue and committed the US to a dramatic effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a level of 50 percent of emissions in 2005 by the year 2030, which will require unprecedented action and cooperation between government and major industries.

By and large, the public’s mood has shifted from one of skepticism to support, but because the issue is so deeply embedded in scientific predictions whose details are often absent in popular discussions, statements from prominent scientists have great potential to influence the debate.

As a theoretical physicist whose primary research has been in what is often called “fundamental physics” I am acutely aware that my colleagues can project an air of superiority in being dismissive of other disciplines and the scientists who labor in them. My late friend and colleague Freeman Dyson was an example. Freeman was one of the smartest physicists I have known, and we spoke at length on a few occasions about climate change. His views, while creative and novel, like almost all of his ideas, were nevertheless woefully uninformed. I suspect he felt that because he was smarter than climate scientists, he distrusted their work.

More here.

In a new, well-documented

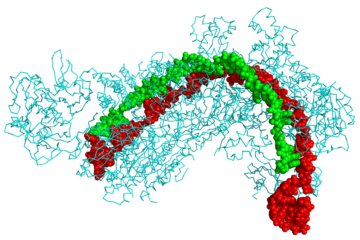

In a new, well-documented  The Nobel prize in chemistry awarded last year to the biochemists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for the genetic modification technique called CRISPR cemented the popular idea that a new era of precision manipulation of hereditary material had arrived. The award came on the heels of the unauthorized use of the technique by the scientist He Jiankui in 2018 in China in an effort to produce individuals (twin girls in this case) resistant to HIV, and a flurry of studies in early 2020 showing that accuracy in altering DNA in a test tube or bacteria in a culture dish, did not hold up when applied to animal embryos. Attempts to modify single genes in human embryos (not intended to be brought to full-term) in fact led to “

The Nobel prize in chemistry awarded last year to the biochemists Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier for the genetic modification technique called CRISPR cemented the popular idea that a new era of precision manipulation of hereditary material had arrived. The award came on the heels of the unauthorized use of the technique by the scientist He Jiankui in 2018 in China in an effort to produce individuals (twin girls in this case) resistant to HIV, and a flurry of studies in early 2020 showing that accuracy in altering DNA in a test tube or bacteria in a culture dish, did not hold up when applied to animal embryos. Attempts to modify single genes in human embryos (not intended to be brought to full-term) in fact led to “ After a decade of fighting for regulatory approval and public acceptance, a biotechnology firm has released genetically engineered mosquitoes into the open air in the United States for the first time. The experiment, launched this week in the Florida Keys — over the objections of some local critics — tests a method for suppressing populations of wild Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which can carry diseases such as Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever.

After a decade of fighting for regulatory approval and public acceptance, a biotechnology firm has released genetically engineered mosquitoes into the open air in the United States for the first time. The experiment, launched this week in the Florida Keys — over the objections of some local critics — tests a method for suppressing populations of wild Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which can carry diseases such as Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever. “The effects of oral states of consciousness,” Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, “are bizarre to the literate mind.” Parry theorized that, if he could find a find a culture where bards still practiced an oral tradition, singing songs as long as Homer’s (over 12,000 lines), he could prove the links between Homeric verse and Bosnian song that scholars had long been puzzling over. In his approach, Parry worked a different field with some of the same purpose Alan Lomax did in the American South during this same period, collecting a rural folk tradition in order to catalog the vast body of American song. The Muslim Slavs of Bosnia, where Parry focused his recording, were called “guslars,” and played a single-string instrument called the “gusle.”

“The effects of oral states of consciousness,” Walter Ong wrote in his 1982 book Orality and Literacy, “are bizarre to the literate mind.” Parry theorized that, if he could find a find a culture where bards still practiced an oral tradition, singing songs as long as Homer’s (over 12,000 lines), he could prove the links between Homeric verse and Bosnian song that scholars had long been puzzling over. In his approach, Parry worked a different field with some of the same purpose Alan Lomax did in the American South during this same period, collecting a rural folk tradition in order to catalog the vast body of American song. The Muslim Slavs of Bosnia, where Parry focused his recording, were called “guslars,” and played a single-string instrument called the “gusle.” Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda.

Beyond all this violent contrarianism, the Lawrence Wilson wishes to paint is a figure of ‘mysteries rather than certainties’. The ‘burning man’ of her title derives from a letter of 1913 in which Lawrence the would-be martyr for his art compares himself to his namesake saint, who famously embraced his martyrdom (death on a gridiron) to the point of proclaiming, ‘Turn me over brothers, I am done enough on this side.’ Wilson’s target is less a straightforward biography than a sifting of Lawrence’s legacy for what remains urgent and alive, the aim being to shed its infernal baggage in search of an abiding paradise. One threat to her Dante comparison is how remote from heaven Lawrence increasingly appears, his attachment to the physical world growing shriller the weaker his grip on it becomes. But these tensions are all part of the drama, not least where the question of sex is concerned. Sex in Lawrence must always be a full-on sacramental affair, but in everyday life he was uptight and prissy about being touched, unlike the more easy-going Frieda. Not so long ago, there seemed to be something radical in rejecting the future. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. In the 1990s, history was over; the United States and capitalism had won. Strutting conservative televangelists and smug liberal technocrats took turns running the world. Globalization promised more of everything: more productivity, more innovation, more wealth. Economic prosperity and regressive moralism went hand in hand. The nuclear family was once again sacred, and non-normative sexuality remained stigmatized: Don’t ask, but also don’t tell. Conservatives—as well as some liberals—supported any policy that promised to protect children, born and unborn, so they might take advantage of the bright future that awaited them. Meritocracy was supposedly thriving, even as inequality prevailed everywhere.

Not so long ago, there seemed to be something radical in rejecting the future. Looking back, it’s easy to see why. In the 1990s, history was over; the United States and capitalism had won. Strutting conservative televangelists and smug liberal technocrats took turns running the world. Globalization promised more of everything: more productivity, more innovation, more wealth. Economic prosperity and regressive moralism went hand in hand. The nuclear family was once again sacred, and non-normative sexuality remained stigmatized: Don’t ask, but also don’t tell. Conservatives—as well as some liberals—supported any policy that promised to protect children, born and unborn, so they might take advantage of the bright future that awaited them. Meritocracy was supposedly thriving, even as inequality prevailed everywhere. The world has gone through a tough time with the COVID-19 pandemic. Every catastrophic event is unique, but there are certain commonalities to how such crises play out in our modern interconnected world. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote a book from a couple of years ago,

The world has gone through a tough time with the COVID-19 pandemic. Every catastrophic event is unique, but there are certain commonalities to how such crises play out in our modern interconnected world. Historian Niall Ferguson wrote a book from a couple of years ago,  The governments of South Africa, India, and dozens of other developing countries are calling for the rights on intellectual property (IP), including vaccine patents, to be waived to accelerate the worldwide production of supplies to fight COVID-19. They are absolutely correct. IP for fighting COVID-19 should be waived, and indeed actively shared among scientists, companies, and nations.

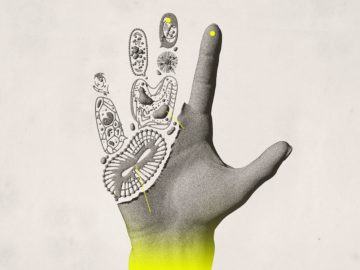

The governments of South Africa, India, and dozens of other developing countries are calling for the rights on intellectual property (IP), including vaccine patents, to be waived to accelerate the worldwide production of supplies to fight COVID-19. They are absolutely correct. IP for fighting COVID-19 should be waived, and indeed actively shared among scientists, companies, and nations. Each year, researchers from around the world gather at Neural Information Processing Systems, an artificial-intelligence conference, to discuss automated translation software, self-driving cars, and abstract mathematical questions. It was odd, therefore, when Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, gave a presentation at the 2018 conference, which was held in Montreal. Fifty-one, with light-green eyes and a dark beard that lend him a mischievous air, Levin studies how bodies grow, heal, and, in some cases, regenerate. He waited onstage while one of Facebook’s A.I. researchers introduced him, to a packed exhibition hall, as a specialist in “computation in the medium of living systems.”

Each year, researchers from around the world gather at Neural Information Processing Systems, an artificial-intelligence conference, to discuss automated translation software, self-driving cars, and abstract mathematical questions. It was odd, therefore, when Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, gave a presentation at the 2018 conference, which was held in Montreal. Fifty-one, with light-green eyes and a dark beard that lend him a mischievous air, Levin studies how bodies grow, heal, and, in some cases, regenerate. He waited onstage while one of Facebook’s A.I. researchers introduced him, to a packed exhibition hall, as a specialist in “computation in the medium of living systems.” I remember the first time I ever saw a ghost. I was tiptoeing through the remnants of a burnt-out row house in Washington, D.C., in one of the neighborhoods where, in the 1990s, one could still discern the architectural scars from the urban rebellions meant to avenge the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., thirty years before.

I remember the first time I ever saw a ghost. I was tiptoeing through the remnants of a burnt-out row house in Washington, D.C., in one of the neighborhoods where, in the 1990s, one could still discern the architectural scars from the urban rebellions meant to avenge the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., thirty years before. In September 2019, about halfway between claiming the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and earning multiple Oscar nominations in January 2020, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite was briefly upstaged by a movie from the director’s past. His second feature, Memories of Murder (2003), had grappled with South Korea’s most chilling cold case: a spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered near Hwaseong, about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. (Song Kang Ho, a star of Parasite, plays one of the police detectives obsessed with nabbing the culprit.) According to a May 2020 CNN story, “About 226,000 people lived in the area, scattered among a number of villages between forested hills and rice paddies,” in a region that previously had reported “no real crime to speak of.” The slaughter began in 1986 and continued for five years. A suspect was jailed for one of the crimes in 1989 and released on parole in 2009; the others, however, went unanswered. The specter of what have been called Korea’s first serial killings profoundly spooked the nation: Police investigated over 20,000 people, some even after the statute of limitations expired in 2006. Over two million “man-days” were devoted to the case—nearly 5,500 years, longer by a millennium than Korea itself has been around. You could think of the investigation as an entire civilization built around a singular depravity.

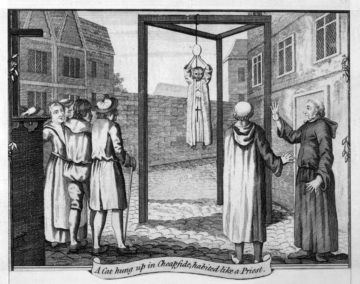

In September 2019, about halfway between claiming the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May and earning multiple Oscar nominations in January 2020, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite was briefly upstaged by a movie from the director’s past. His second feature, Memories of Murder (2003), had grappled with South Korea’s most chilling cold case: a spree in which ten women and girls were raped and murdered near Hwaseong, about twenty-six miles south of Seoul. (Song Kang Ho, a star of Parasite, plays one of the police detectives obsessed with nabbing the culprit.) According to a May 2020 CNN story, “About 226,000 people lived in the area, scattered among a number of villages between forested hills and rice paddies,” in a region that previously had reported “no real crime to speak of.” The slaughter began in 1986 and continued for five years. A suspect was jailed for one of the crimes in 1989 and released on parole in 2009; the others, however, went unanswered. The specter of what have been called Korea’s first serial killings profoundly spooked the nation: Police investigated over 20,000 people, some even after the statute of limitations expired in 2006. Over two million “man-days” were devoted to the case—nearly 5,500 years, longer by a millennium than Korea itself has been around. You could think of the investigation as an entire civilization built around a singular depravity. The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.