Jeffrey Kastner at Cabinet Magazine:

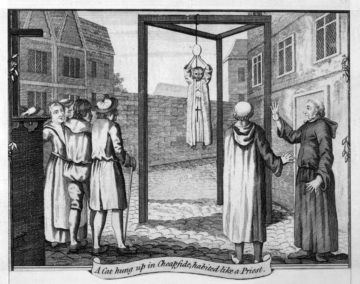

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.2 Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”3 to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.2 Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”3 to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

more here.