And Applaud

Once a young man came to me and said,

Dear Master,

I am feeling strong and brave today,

And I would like to know the truth

About all of my —attachments.

And I replied,

Attachments?

Attachments!

Sweet Heart,

Do you really want me to speak to you

About all your attachments,

When I can see so clearly

You have built, with so much care,

Such a great brothel

To house all of your pleasures.

You have even surrounded the whole damn place

With armed guards and vicious dogs

To protect your desires

So that you can sneak away

From time to time

And try to squeeze light

Into your parched being

From a source as fruitful

As a dried date pit

That even a bird

Is wise enough to spit out.

Your attachments! My dear,

Let’s not speak of those,

For Hafiz knows

The torments and agonies

That every mind on the way to Annihilation in the sun

Must endure.

So at night in my prayers I often stop

And ask a thousand angels to join in

And applaud

Anything

Anything in this world

That can bring your heart comfort.

by Hafiz

rendition by Daniel Ladinsky

from I Heard God Laughing

Penguin Books, 2006

THE DAY BEFORE

THE DAY BEFORE GET BIG FAST was an early Amazon motto. The slogan sounds like a fratty refrain tossed around at the gym. Jeff Bezos had it printed on T-shirts. More than twenty-five years after leaving his position as a Wall Street hedge-fund executive to found Amazon, Bezos’s size anxiety is long gone. (At least as it pertains to his company; the CEO’s Washington, DC, house has eleven bedrooms and twenty-five bathrooms, a bedroom-to-bathroom ratio that raises both architectural and scatological questions.) Bezos is now worth $180 billion. Amazon, were it a country, would have a larger GDP than Australia.

GET BIG FAST was an early Amazon motto. The slogan sounds like a fratty refrain tossed around at the gym. Jeff Bezos had it printed on T-shirts. More than twenty-five years after leaving his position as a Wall Street hedge-fund executive to found Amazon, Bezos’s size anxiety is long gone. (At least as it pertains to his company; the CEO’s Washington, DC, house has eleven bedrooms and twenty-five bathrooms, a bedroom-to-bathroom ratio that raises both architectural and scatological questions.) Bezos is now worth $180 billion. Amazon, were it a country, would have a larger GDP than Australia. Zachary D. Carter in the New York Times:

Zachary D. Carter in the New York Times: Gregory Kaebnick in Boston Review:

Gregory Kaebnick in Boston Review: Katie Kheriji-Watts in Hyperallergic:

Katie Kheriji-Watts in Hyperallergic: Jennifer Wilson in The Nation:

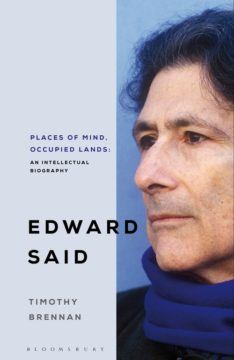

Jennifer Wilson in The Nation: Adam Shatz in the LRB:

Adam Shatz in the LRB: F

F Early in her career, Alison Bechdel, then a cult cartoonist — “at the pinnacle of my bitterness,” she would later say — was invited to contribute to a special gay pride issue of Seattle’s alternative newspaper The Stranger. She fired off a comic strip titled “Oppressed Minority Cartoonist.” She drew herself at her desk, flanked by a bottle of Scotch, mid-tirade. Why had her work been pigeonholed? And why had she complied so willingly, chronicling only lesbians, her “oppressed minority group”? In the last panel, her rant is interrupted by a phone call inviting her to contribute to that very gay pride issue. “I’d be honored,” she capitulates.

Early in her career, Alison Bechdel, then a cult cartoonist — “at the pinnacle of my bitterness,” she would later say — was invited to contribute to a special gay pride issue of Seattle’s alternative newspaper The Stranger. She fired off a comic strip titled “Oppressed Minority Cartoonist.” She drew herself at her desk, flanked by a bottle of Scotch, mid-tirade. Why had her work been pigeonholed? And why had she complied so willingly, chronicling only lesbians, her “oppressed minority group”? In the last panel, her rant is interrupted by a phone call inviting her to contribute to that very gay pride issue. “I’d be honored,” she capitulates. To get this out of the way: Destroying the coronavirus is, without question, paramount. Millions of people are dead, and tens of thousands more die every week. At the same time, the majority of the trillions of microbes that inhabit our skin and gut—collectively, our microbiome—are either

To get this out of the way: Destroying the coronavirus is, without question, paramount. Millions of people are dead, and tens of thousands more die every week. At the same time, the majority of the trillions of microbes that inhabit our skin and gut—collectively, our microbiome—are either  Few documents are venerated as much as the American constitution. Until recently, one million people a year filed past the original copy on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in Washington DC. Yet, as Linda Colley’s brilliant new book shows, viewing constitutions as national tablets of stone tells us more about their contemporary charisma than the complex histories from which they were wrought. In this compelling study of constitutions produced around the world between the mid-18th century and the outbreak of the first world war, she upends the familiar version of history at every turn. Out goes the myth that constitutions were the product of democratic aspirations or revolution – rather they arose from the ashes of war or the threat of invasion. Nations may have been girded by constitutional documents, but these were borderless texts, available for adaptation across time and space. Above all, constitutions were “protean and volatile pieces of technology” that travelled far and wide, assisted by the expansion of print media and the speeding-up of long-distance travel and communication.

Few documents are venerated as much as the American constitution. Until recently, one million people a year filed past the original copy on display in the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in Washington DC. Yet, as Linda Colley’s brilliant new book shows, viewing constitutions as national tablets of stone tells us more about their contemporary charisma than the complex histories from which they were wrought. In this compelling study of constitutions produced around the world between the mid-18th century and the outbreak of the first world war, she upends the familiar version of history at every turn. Out goes the myth that constitutions were the product of democratic aspirations or revolution – rather they arose from the ashes of war or the threat of invasion. Nations may have been girded by constitutional documents, but these were borderless texts, available for adaptation across time and space. Above all, constitutions were “protean and volatile pieces of technology” that travelled far and wide, assisted by the expansion of print media and the speeding-up of long-distance travel and communication.