Discontinuous Poems

Though all my poems are different,

Because each thing that exists is always proclaiming it.

Sometimes I busy myself with watching a stone,

I don’t begin thinking whether it feels.

I don’t force myself to call it my sister,

But I enjoy it because of its being a stone,

I enjoy it because it feels nothing,

I enjoy it because it is not at all related to me.

At times I also hear the wind blow by

And find that merely to hear the wind blow makes

…….. it worth having been born.

I don’t know what others will think who read this;

But I find it must be good because I think it

…….. without effort,

And without the idea of others hearing me think,

Because I think it without thoughts,

Because I say it as my words say it.

Once they called me a materialist poet

And I admired myself because I never thought

That I might be called by any name at all.

I am not even a poet: I see.

If what I write has any value, it is not I who am

…….. valuable.

The value is there. In my verses.

All this has nothing whatever to do with any will

…….. of mine.

by Fernando Pessoa

from the Poetry Foundation

Editorial note: Until I read this poem I’d never encountered a poem that so accurately expresses what writing a poem is, is about, or for that matter, what the creative experience itself is. —Jim

In September 2017, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, the storm first made landfall on a small island off the main island’s eastern coast called Cayo Santiago. At the time, the fate of Cayo Santiago and its inhabitants was barely a footnote in the dramatic story of Maria, which became Puerto Rico’s worst natural disaster, killing 3,000 people and disrupting normal life for months.

In September 2017, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, the storm first made landfall on a small island off the main island’s eastern coast called Cayo Santiago. At the time, the fate of Cayo Santiago and its inhabitants was barely a footnote in the dramatic story of Maria, which became Puerto Rico’s worst natural disaster, killing 3,000 people and disrupting normal life for months. JERUSALEM — The annual Israel Prize ceremony is supposed to be an august and unifying event, a beloved highlight of the Independence Day celebrations that fall on Thursday this year. This being Israel, it is rarely without controversy. The latest ruckus goes to the heart of the political divides and culture wars rocking the country’s liberal democratic foundations even as it remains lodged in a two-year

JERUSALEM — The annual Israel Prize ceremony is supposed to be an august and unifying event, a beloved highlight of the Independence Day celebrations that fall on Thursday this year. This being Israel, it is rarely without controversy. The latest ruckus goes to the heart of the political divides and culture wars rocking the country’s liberal democratic foundations even as it remains lodged in a two-year  It’s hard if not impossible to imagine a figure of Weil’s stature in the intellectual and political culture of today’s left, the only region of the political spectrum where she might possibly fit. And not just because of her religiosity, which would of course instantly ghettoize her. It’s also because she’s so hard to pin down with any neat, easy label—or rather, because the labels are too many and apparently conflicting. (She’d be eaten alive on Twitter from all sides—or, worse, simply shunned and ignored.) “An anarchist who espoused conservative ideals,” Zaretsky writes in his opening pages, “a pacifist who fought in the Spanish Civil War, a saint who refused baptism, a mystic who was a labor militant, a French Jew who was buried in the Catholic section of an English cemetery, a teacher who dismissed the importance of solving a problem, the most willful of individuals who advocated the extinction of the self: here are but a few of the paradoxes Weil embodied.”

It’s hard if not impossible to imagine a figure of Weil’s stature in the intellectual and political culture of today’s left, the only region of the political spectrum where she might possibly fit. And not just because of her religiosity, which would of course instantly ghettoize her. It’s also because she’s so hard to pin down with any neat, easy label—or rather, because the labels are too many and apparently conflicting. (She’d be eaten alive on Twitter from all sides—or, worse, simply shunned and ignored.) “An anarchist who espoused conservative ideals,” Zaretsky writes in his opening pages, “a pacifist who fought in the Spanish Civil War, a saint who refused baptism, a mystic who was a labor militant, a French Jew who was buried in the Catholic section of an English cemetery, a teacher who dismissed the importance of solving a problem, the most willful of individuals who advocated the extinction of the self: here are but a few of the paradoxes Weil embodied.” Beyond erasing this diversity, casting Palestinian radicalism as innately Islamic severs resistance from the essential question of land and geography. The novel reflects this: Nahr’s status as the daughter of Palestinian refugees in Kuwait certainly affects her life—she is pushed out of an official dance troupe, and her family’s allegiance is suspected after Saddam Hussein’s invasion. But being Palestinian doesn’t take hold as a political reality until she lives in her ancestral homeland. What fuels her fight isn’t a divine commandment about good and evil; it is the land itself. Nahr observes settlers encroaching on a Palestinian village, and wonders how Bilal and his mother have been able to keep them away from their land. She visits her mother’s childhood home, in Haifa, and picks figs from a tree her grandfather planted, before being chased off by a Jewish woman who now lives there. She helps to redirect water from a pipe meant for settlers to the olive groves. There is violence inflicted upon this land, but Abulhawa centers its beauty: “I was content to just sit there in the splendid silence of the hills, where the quiet amplified small sounds—the wind rustling trees; sheep chewing, roaming, bleating, breathing; the soft crackle of the fire; the purr of Bilal’s breathing,” Nahr reflects. “I realized how much I had come to love these hills; how profound was my link to this soil.”

Beyond erasing this diversity, casting Palestinian radicalism as innately Islamic severs resistance from the essential question of land and geography. The novel reflects this: Nahr’s status as the daughter of Palestinian refugees in Kuwait certainly affects her life—she is pushed out of an official dance troupe, and her family’s allegiance is suspected after Saddam Hussein’s invasion. But being Palestinian doesn’t take hold as a political reality until she lives in her ancestral homeland. What fuels her fight isn’t a divine commandment about good and evil; it is the land itself. Nahr observes settlers encroaching on a Palestinian village, and wonders how Bilal and his mother have been able to keep them away from their land. She visits her mother’s childhood home, in Haifa, and picks figs from a tree her grandfather planted, before being chased off by a Jewish woman who now lives there. She helps to redirect water from a pipe meant for settlers to the olive groves. There is violence inflicted upon this land, but Abulhawa centers its beauty: “I was content to just sit there in the splendid silence of the hills, where the quiet amplified small sounds—the wind rustling trees; sheep chewing, roaming, bleating, breathing; the soft crackle of the fire; the purr of Bilal’s breathing,” Nahr reflects. “I realized how much I had come to love these hills; how profound was my link to this soil.”

A year ago, there was no snow on the ground, and I was thinking about icebergs. “We’d rather have the iceberg than the ship,” begins the first stanza of Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Imaginary Iceberg,” and continues,

A year ago, there was no snow on the ground, and I was thinking about icebergs. “We’d rather have the iceberg than the ship,” begins the first stanza of Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Imaginary Iceberg,” and continues, The announcement of a new Haruki Murakami title inspires gleeful anticipation: Will there be music (classical, jazz, Beatles – yes), baseball (certainly), local watering holes (take a seat), thwarted young love (indubitably), the impossible made ordinary (naturally), and … cats (meow)? The Japanese writer doesn’t disappoint in his latest collection to arrive stateside, “First Person Singular,” a phrase that also succinctly summarizes his preferred writing style: The eight stories are each revealed by a contemplative “I”-narrator. Over the 40-plus years Murakami has produced novels, short stories, nonfiction, and personal essays, he’s first and foremost a remarkably accessible storyteller. His books are an intimate invitation to revel in his perpetually unpredictable, yet remarkably convincing, imagination.

The announcement of a new Haruki Murakami title inspires gleeful anticipation: Will there be music (classical, jazz, Beatles – yes), baseball (certainly), local watering holes (take a seat), thwarted young love (indubitably), the impossible made ordinary (naturally), and … cats (meow)? The Japanese writer doesn’t disappoint in his latest collection to arrive stateside, “First Person Singular,” a phrase that also succinctly summarizes his preferred writing style: The eight stories are each revealed by a contemplative “I”-narrator. Over the 40-plus years Murakami has produced novels, short stories, nonfiction, and personal essays, he’s first and foremost a remarkably accessible storyteller. His books are an intimate invitation to revel in his perpetually unpredictable, yet remarkably convincing, imagination. There exists a social hierarchy within

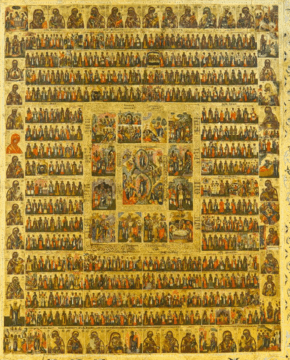

There exists a social hierarchy within  In a new collection of Gogol’s short stories, translated by Susanne Fusso, a professor of Russian studies at Wesleyan University, readers are reintroduced to the familiar cast of characters—identified by their rank, of course—that populate many of the Ukrainian author’s most celebrated works, including “The Nose” and “The Overcoat.” There are the titular councillors, the collegiate assessors, the section heads of unnamed departments, the recently promoted (and thus insufferable). In short, the book’s stories cover nearly all manner of pompous, status-obsessed, careerist bureaucrats. It could be said that the Table of Ranks defined Gogol’s narrative landscape, but what is also true is that Gogol in turn redefined the Table of Ranks for his readers, then and now. As the scholar Irina Reyfman notes, “To a large degree, the way people now think of the world of state service is determined by Gogol’s portrayal of it in his fiction.”

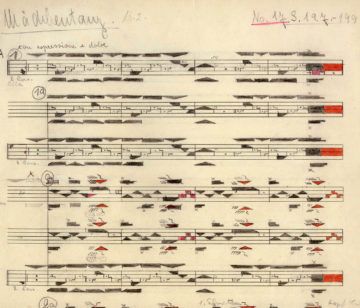

In a new collection of Gogol’s short stories, translated by Susanne Fusso, a professor of Russian studies at Wesleyan University, readers are reintroduced to the familiar cast of characters—identified by their rank, of course—that populate many of the Ukrainian author’s most celebrated works, including “The Nose” and “The Overcoat.” There are the titular councillors, the collegiate assessors, the section heads of unnamed departments, the recently promoted (and thus insufferable). In short, the book’s stories cover nearly all manner of pompous, status-obsessed, careerist bureaucrats. It could be said that the Table of Ranks defined Gogol’s narrative landscape, but what is also true is that Gogol in turn redefined the Table of Ranks for his readers, then and now. As the scholar Irina Reyfman notes, “To a large degree, the way people now think of the world of state service is determined by Gogol’s portrayal of it in his fiction.” To the untrained eye, Kinetography looks esoteric and occult, but to the few who can read it the complex strips of hieroglyphs allow them to recreate dances much as their original choreographers imagined them. Dance notation was invented in seventeenth-century France to score court dances and classical ballet, but it recorded only formal footsteps and by Laban’s time it was largely forgotten. Laban’s dream was to create a “universally applicable” notation that could capture the frenzy and nuance of modern dance, and he developed a system of 1,421 abstract symbols to record the dancer’s every movement in space, as well as the energy level and timing with which they were made. He hoped that his code would elevate dance to its rightful place in the hierarchy of arts, “alongside literature and music,” and that one day everyone would be able to read it fluently.

To the untrained eye, Kinetography looks esoteric and occult, but to the few who can read it the complex strips of hieroglyphs allow them to recreate dances much as their original choreographers imagined them. Dance notation was invented in seventeenth-century France to score court dances and classical ballet, but it recorded only formal footsteps and by Laban’s time it was largely forgotten. Laban’s dream was to create a “universally applicable” notation that could capture the frenzy and nuance of modern dance, and he developed a system of 1,421 abstract symbols to record the dancer’s every movement in space, as well as the energy level and timing with which they were made. He hoped that his code would elevate dance to its rightful place in the hierarchy of arts, “alongside literature and music,” and that one day everyone would be able to read it fluently. One of the most intriguing moments in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s magisterial

One of the most intriguing moments in Claude Lévi-Strauss’s magisterial  Telling a story seems like the most natural, human thing in the world. We all do it, all the time. And who amongst us doesn’t think we could be a fairly competent novelist, if we just bothered to take the time? But storytelling is a craft like any other, with its own secret techniques and best practices. Charlie Jane Anders is a multiple-award-winning novelist and story writer, but also someone who has thought carefully about all the ingredients of a good story, from plot and conflict to characters and relationships. This will be a useful conversation for anyone who tells stories, reads books, or watches movies. Maybe you’ll be inspired to finally write that novel.

Telling a story seems like the most natural, human thing in the world. We all do it, all the time. And who amongst us doesn’t think we could be a fairly competent novelist, if we just bothered to take the time? But storytelling is a craft like any other, with its own secret techniques and best practices. Charlie Jane Anders is a multiple-award-winning novelist and story writer, but also someone who has thought carefully about all the ingredients of a good story, from plot and conflict to characters and relationships. This will be a useful conversation for anyone who tells stories, reads books, or watches movies. Maybe you’ll be inspired to finally write that novel.