Ursula Kenny in The Guardian:

Catherine Menon was born in Perth, Western Australia, where her British mother and Malaysian father met. She lectures in robotics and has a PhD in pure mathematics as well as an MA in creative writing. Fragile Monsters, her first novel, is set in rural Malaysia and unpicks a family’s story from 1920 to the present day. At its centre are Mary, “sharp tongued and ferocious”, and her visiting granddaughter, Durga, who tussle over the demons and dark memories that distort their past and warp the present. Hilary Mantel has described Menon’s writing as “supple, artful, skilful storytelling” and she has won awards for her short stories. She is married to a fellow mathematician and lives in north London.

Catherine Menon was born in Perth, Western Australia, where her British mother and Malaysian father met. She lectures in robotics and has a PhD in pure mathematics as well as an MA in creative writing. Fragile Monsters, her first novel, is set in rural Malaysia and unpicks a family’s story from 1920 to the present day. At its centre are Mary, “sharp tongued and ferocious”, and her visiting granddaughter, Durga, who tussle over the demons and dark memories that distort their past and warp the present. Hilary Mantel has described Menon’s writing as “supple, artful, skilful storytelling” and she has won awards for her short stories. She is married to a fellow mathematician and lives in north London.

Why did you want to write about Malaysia?

The idea came from the stories my father used to tell me about when he was young – appropriately sanitised. It wasn’t until I was in my teens that I even realised that Kuala Lipis [where his family lived] was the head of Japanese activities in Pahang [state]. During the second world war it was very much under Japanese control. It was at the centre of things like food rationing; the children’s education was wildly interrupted and when it was resumed it was all in Japanese. So all sorts of upheavals that I really only came to understand when I started researching.

More here.

A massive landslide—the worst in decades—struck Du Fangming’s home in south China’s Hunan province on July 6. “My house collapsed. My goats were swept away by the mud,” he told Chinese media outlets shortly after the catastrophe. Fortunately, though, he was safe—one of 33 villagers who had been evacuated thanks to early warnings enabled by advanced positioning technologies that can provide more accurate readings than ever before.

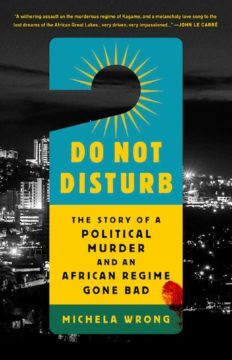

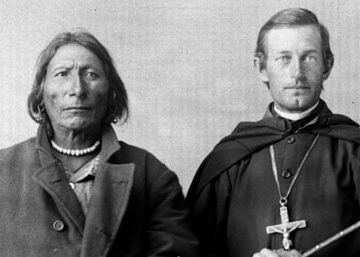

A massive landslide—the worst in decades—struck Du Fangming’s home in south China’s Hunan province on July 6. “My house collapsed. My goats were swept away by the mud,” he told Chinese media outlets shortly after the catastrophe. Fortunately, though, he was safe—one of 33 villagers who had been evacuated thanks to early warnings enabled by advanced positioning technologies that can provide more accurate readings than ever before. In the view of most historians, the original sin of Rwanda came from the colonial policy of making artificial ethnic distinctions through a caste-like system. Belgian administrators deemed those who were taller and herded cattle, the Tutsis, to be smarter than the Hutu, who were generally shorter and raised crops. So one group got all the privileges of helping the Belgians extract coffee and animal hides and were treated as sub-royals, while their countrymen were deemed slow and stupid. The story was fixed; the Goods and Bads had been preselected, and the inevitable resentments would explode in the 1994 genocide.

In the view of most historians, the original sin of Rwanda came from the colonial policy of making artificial ethnic distinctions through a caste-like system. Belgian administrators deemed those who were taller and herded cattle, the Tutsis, to be smarter than the Hutu, who were generally shorter and raised crops. So one group got all the privileges of helping the Belgians extract coffee and animal hides and were treated as sub-royals, while their countrymen were deemed slow and stupid. The story was fixed; the Goods and Bads had been preselected, and the inevitable resentments would explode in the 1994 genocide. WHAT IS THE POINT

WHAT IS THE POINT  Few writers have borne witness to the slow-healing bruises of early neglect more memorably than Cynthia Ozick, whose own first novel, “

Few writers have borne witness to the slow-healing bruises of early neglect more memorably than Cynthia Ozick, whose own first novel, “ Alissa Wilkinson in Vox:

Alissa Wilkinson in Vox: David Barsamian interviews Noam Chomsky in Boston Review:

David Barsamian interviews Noam Chomsky in Boston Review: If power were

If power were  Perhaps the most striking political change that occurred during the stormy reign of Donald J. Trump is one his devotees utterly abhorred: the growth of a sizable left outside and inside the Democratic Party. Young radicals and middle-aged white suburban dwellers both flocked to “the Resistance,” under whose militant rubric one could do anything from marching in a demonstration to starting a Facebook page to canvassing for a favored candidate. During his second run for the White House even more than during his first, Bernie Sanders inspired millions of young people of all races to imagine living in a nation with strong unions and a robust welfare state instead of the “neoliberal” order long favored by leaders of both major parties. And, for many Berniecrats, socialism became the name of their desire instead of a synonym for state tyranny.

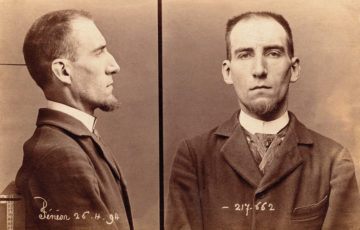

Perhaps the most striking political change that occurred during the stormy reign of Donald J. Trump is one his devotees utterly abhorred: the growth of a sizable left outside and inside the Democratic Party. Young radicals and middle-aged white suburban dwellers both flocked to “the Resistance,” under whose militant rubric one could do anything from marching in a demonstration to starting a Facebook page to canvassing for a favored candidate. During his second run for the White House even more than during his first, Bernie Sanders inspired millions of young people of all races to imagine living in a nation with strong unions and a robust welfare state instead of the “neoliberal” order long favored by leaders of both major parties. And, for many Berniecrats, socialism became the name of their desire instead of a synonym for state tyranny. The bulk of Fénéon’s art writing has never been translated. For anglophone audiences, he is probably better known for his “Novels in Three Lines,” a litany of more than one thousand mini-tragedies and absurdities published anonymously in 1906 during the half year he spent writing news items for Le Matin, an American-style mass-circulation newspaper founded by a disciple of William Randolph Hearst. These faits divers, of which Luc Sante published an acclaimed translation in 2007, make for reading that is melancholy but piquant. They include random reports such as “On the left shoulder of a newborn, whose corpse was found near the 22nd Artillery barracks, a tattoo: a cannon.” Or: “The sinister prowler seen by the mechanic Gicquel near Herblay train station has been identified: Jules Ménard, snail collector.”

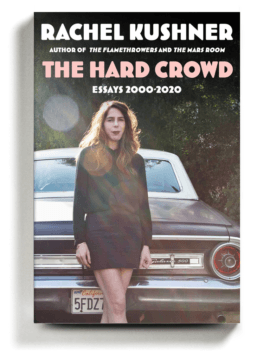

The bulk of Fénéon’s art writing has never been translated. For anglophone audiences, he is probably better known for his “Novels in Three Lines,” a litany of more than one thousand mini-tragedies and absurdities published anonymously in 1906 during the half year he spent writing news items for Le Matin, an American-style mass-circulation newspaper founded by a disciple of William Randolph Hearst. These faits divers, of which Luc Sante published an acclaimed translation in 2007, make for reading that is melancholy but piquant. They include random reports such as “On the left shoulder of a newborn, whose corpse was found near the 22nd Artillery barracks, a tattoo: a cannon.” Or: “The sinister prowler seen by the mechanic Gicquel near Herblay train station has been identified: Jules Ménard, snail collector.” Her own motorcycles come to include an orange 500 cc Moto Guzzi, a Kawasaki Ninja and a Cagiva Elefant 650. Her boyfriends tended to be mechanics.

Her own motorcycles come to include an orange 500 cc Moto Guzzi, a Kawasaki Ninja and a Cagiva Elefant 650. Her boyfriends tended to be mechanics.