Morgan Meis at Slant Books:

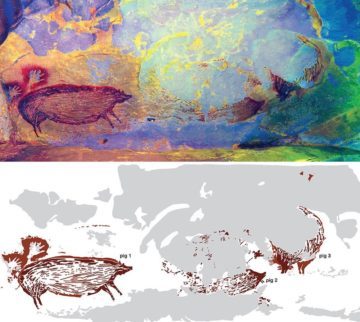

The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time.

The warty pig in question is a depiction on the inside of a cave in Indonesia. The painting was discovered last year. It was painted, the carbon daters say, about 45,000 years ago. That’s more than 10,000 years older than the famous paintings at the Chauvet Cave in France. Warty pig is, for now at least, the oldest work of representational art, by far, that exists anywhere in the world. 45,000 years. A long time. Also not a long time, geologically speaking. Just a blip. For us, though, for us, a very long time.

Anyway, the painter of warty pig, whoever this person was, seems to have been working on a domestic scene going on between at least three warty pigs. And what might have been the important business amongst the warty pigs on the island of Sulawesi during the forty-fifth-thousand-and-first century BCE? Well, the Sulawesi warty pig lives on the island to this very day. So, we have a pretty good sense of what the pig would have been doing 45,000 years ago. It would have been wandering around in the mornings and early evenings, rooting around in the underbrush looking for goodies to eat. It would have been working out whatever things needed to be worked out in the small social groups in which the pigs tend to live. Maybe that’s what the cave painting is showing us, an impromptu meeting of warty pigs 45,000 years ago. Unfortunately, the images of the other pigs have been lost to us but for a few scraps of color and shape. We’ll never know exactly what was the greater context for this image.

But here are a few things that I love about this fragment that has passed down to us from the deepest recesses of the past.

More here.

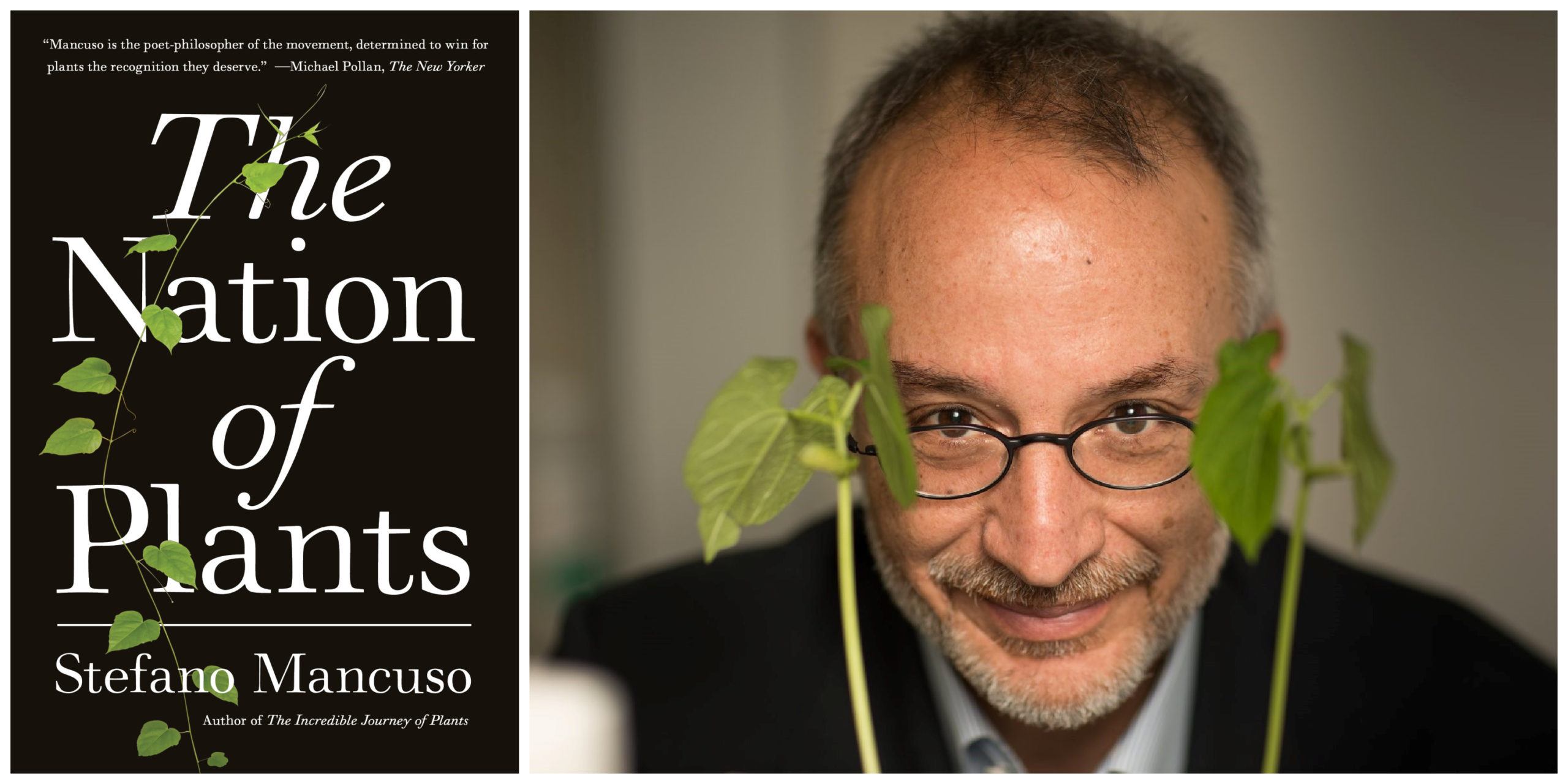

Darwin writes: what animals could you imagine to be more distant from one another than a cat and a bumblebee? Yet the ties that bind these two animals, though at first glance nonexistent, are on the contrary so strict that were they to be modified, the consequences would be so numerous and profound as to be unimaginable. Mice, argues Darwin, are among the principal enemies of bumblebees. They eat their larvae and destroy their nests. On the other hand, as everyone knows, mice are the favorite prey of cats. One consequence of this is that, in proximity to those villages with the most cats, one finds fewer mice and more bumblebees. So far so clear? Good, let’s go on.

Darwin writes: what animals could you imagine to be more distant from one another than a cat and a bumblebee? Yet the ties that bind these two animals, though at first glance nonexistent, are on the contrary so strict that were they to be modified, the consequences would be so numerous and profound as to be unimaginable. Mice, argues Darwin, are among the principal enemies of bumblebees. They eat their larvae and destroy their nests. On the other hand, as everyone knows, mice are the favorite prey of cats. One consequence of this is that, in proximity to those villages with the most cats, one finds fewer mice and more bumblebees. So far so clear? Good, let’s go on. Over the past decade, populism has emerged as an invasive species which has disrupted a previously stable political ecosystem. Liberal democracies across the world have been left in disarray, and occasional victories by establishment parties offer only temporary respite from its onslaught. That is an interpretation that Prospect readers—and all “right-thinking” opinion—will by now have heard many times.

Over the past decade, populism has emerged as an invasive species which has disrupted a previously stable political ecosystem. Liberal democracies across the world have been left in disarray, and occasional victories by establishment parties offer only temporary respite from its onslaught. That is an interpretation that Prospect readers—and all “right-thinking” opinion—will by now have heard many times.

Those who find writing a chore are better off not knowing about the literary method of

Those who find writing a chore are better off not knowing about the literary method of  In 1792, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) became gravely ill. His convalescence and recovery lasted for more than a year, leaving him completely deaf. (Lead poisoning was suspected.) Had he died right then, at the age of forty-six, Goya would have been remembered as a competent, even elegant, Rococo painter with realist tendencies, but nothing more. Instead, his illness transformed him into an extraordinary artist, one marked by great emotional depth and inventive formal technique.

In 1792, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746–1828) became gravely ill. His convalescence and recovery lasted for more than a year, leaving him completely deaf. (Lead poisoning was suspected.) Had he died right then, at the age of forty-six, Goya would have been remembered as a competent, even elegant, Rococo painter with realist tendencies, but nothing more. Instead, his illness transformed him into an extraordinary artist, one marked by great emotional depth and inventive formal technique. Sanders retained a feel for the joyful and raucous immediacy of R. & B. The producer Ed Michel later said, “Pharoah would take an R&B lick and shake it until it vibrated to death, into freedom.” But he soon became a star of the new, experimental wave of sixties jazz, often referred to as the “New Thing” or “free jazz.” At the time, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and others were breaking from traditional approaches to rhythm and harmonic structure. Sanders’s compositions were open and atmospheric, and his playing moved restlessly between smooth, serene melodies and blaring, hyperactive improvisations. You didn’t passively listen to someone like Sanders so much as receive a transference of energy or take in a brilliant explosion of light. Not everyone was ready for it.

Sanders retained a feel for the joyful and raucous immediacy of R. & B. The producer Ed Michel later said, “Pharoah would take an R&B lick and shake it until it vibrated to death, into freedom.” But he soon became a star of the new, experimental wave of sixties jazz, often referred to as the “New Thing” or “free jazz.” At the time, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and others were breaking from traditional approaches to rhythm and harmonic structure. Sanders’s compositions were open and atmospheric, and his playing moved restlessly between smooth, serene melodies and blaring, hyperactive improvisations. You didn’t passively listen to someone like Sanders so much as receive a transference of energy or take in a brilliant explosion of light. Not everyone was ready for it. WHEN I FIRST held a book bound in human skin, the little hairs on my neck did not stand up, and chills did not run down my spine. The book looked unremarkable; its pale-yellow binding blended in with its antiquarian neighbors on the shelf. I was holding Des Destinées de l’âme (Destiny of the Soul) by philosopher Arsène Houssaye and standing in the bowels of Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript repository. As a graduate student, I had been hired to truck material between the underground stacks and the reading room, where researchers came from all over the world to pore over the library’s collections. Not long after I arrived, Harvard announced that the 19th-century philosophical treatise I held in my hands was the first proven example using peptide mass fingerprinting of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the practice of binding books in human skin. (Human: anthropos; skin: derma; book: biblion; fasten: pegia.) At my first opportunity, I stole away on a break to get a look at the volume. Holding the book didn’t give me goosebumps, but it did raise many questions. Whose skin was this? What kind of person would bind a book in human skin? And why?

WHEN I FIRST held a book bound in human skin, the little hairs on my neck did not stand up, and chills did not run down my spine. The book looked unremarkable; its pale-yellow binding blended in with its antiquarian neighbors on the shelf. I was holding Des Destinées de l’âme (Destiny of the Soul) by philosopher Arsène Houssaye and standing in the bowels of Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript repository. As a graduate student, I had been hired to truck material between the underground stacks and the reading room, where researchers came from all over the world to pore over the library’s collections. Not long after I arrived, Harvard announced that the 19th-century philosophical treatise I held in my hands was the first proven example using peptide mass fingerprinting of anthropodermic bibliopegy, the practice of binding books in human skin. (Human: anthropos; skin: derma; book: biblion; fasten: pegia.) At my first opportunity, I stole away on a break to get a look at the volume. Holding the book didn’t give me goosebumps, but it did raise many questions. Whose skin was this? What kind of person would bind a book in human skin? And why? So how are we to gauge the 4.2-sigma discrepancy between the Standard Model’s prediction and the new measurement? First of all, it is helpful to remember the reason that particle physicists use the five-sigma standard to begin with. The reason is not so much that particle physics is somehow intrinsically more precise than other areas of science or that particle physicists are so much better at doing experiments. It’s primarily that particle physicists have a lot of data. And the more data you have, the more likely you are to find random fluctuations that coincidentally look like a signal. Particle physicists began to commonly use the five-sigma criterion in the mid-1990s to save themselves from the embarrassment of having too many “discoveries” that later turn out to be mere statistical fluctuations.

So how are we to gauge the 4.2-sigma discrepancy between the Standard Model’s prediction and the new measurement? First of all, it is helpful to remember the reason that particle physicists use the five-sigma standard to begin with. The reason is not so much that particle physics is somehow intrinsically more precise than other areas of science or that particle physicists are so much better at doing experiments. It’s primarily that particle physicists have a lot of data. And the more data you have, the more likely you are to find random fluctuations that coincidentally look like a signal. Particle physicists began to commonly use the five-sigma criterion in the mid-1990s to save themselves from the embarrassment of having too many “discoveries” that later turn out to be mere statistical fluctuations.

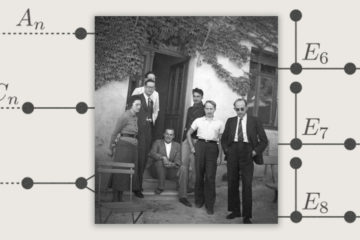

In 1935, one of France’s leading mathematicians, Élie Cartan, received a letter of introduction to Nicolas Bourbaki, along with an article submitted on Bourbaki’s behalf for publication in the journal Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (Proceedings of the French Academy of Sciences). The letter, written by fellow mathematician André Weil, described Bourbaki as a reclusive author passing his days playing cards in the Paris suburb of Clichy, without any pretense of overturning the foundations of all of mathematics (that more disruptive part of Bourbaki’s oeuvre and ambitions

In 1935, one of France’s leading mathematicians, Élie Cartan, received a letter of introduction to Nicolas Bourbaki, along with an article submitted on Bourbaki’s behalf for publication in the journal Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (Proceedings of the French Academy of Sciences). The letter, written by fellow mathematician André Weil, described Bourbaki as a reclusive author passing his days playing cards in the Paris suburb of Clichy, without any pretense of overturning the foundations of all of mathematics (that more disruptive part of Bourbaki’s oeuvre and ambitions

Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan has once again

Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan has once again  IN A NABOKOV short story from 1945, some cultured English people hobnob about the Dresden bombing at a cocktail party: “‘My Dresden no longer exists,’ said Mrs. Mulberry. ‘Our bombs have destroyed it and everything it meant.’” For Anglo-Americans since World War II, Dresden has become an icon of ruin, first moral then physical — a sensational reminder of the evils of war. Recent histories like Sinclair McKay’s Dresden (2020) tend to conjure the firestorm as an act of sheer destruction, a brutish assault on a culture city that, if you squinted, was comparable to Vienna or Paris. (Such accounts tend to overstate Dresden’s innocence — the city was an important site for industry and transportation.) Heavily bombed during the war, then only haltingly rebuilt by Communist East Germany (GDR), Dresden is now a global symbol for atrocity against the run of play.

IN A NABOKOV short story from 1945, some cultured English people hobnob about the Dresden bombing at a cocktail party: “‘My Dresden no longer exists,’ said Mrs. Mulberry. ‘Our bombs have destroyed it and everything it meant.’” For Anglo-Americans since World War II, Dresden has become an icon of ruin, first moral then physical — a sensational reminder of the evils of war. Recent histories like Sinclair McKay’s Dresden (2020) tend to conjure the firestorm as an act of sheer destruction, a brutish assault on a culture city that, if you squinted, was comparable to Vienna or Paris. (Such accounts tend to overstate Dresden’s innocence — the city was an important site for industry and transportation.) Heavily bombed during the war, then only haltingly rebuilt by Communist East Germany (GDR), Dresden is now a global symbol for atrocity against the run of play. The thing about big plans is that they require people to carry them out. The problem of personnel particularly plagued Peter the Great. Convinced by his European advisers that his country was backward and stuck in a medieval mindset, he spent much of his reign on a series of modernizing initiatives intended to get Russia “caught up” with the West. To implement his reforms—which included establishing a navy, imposing a tax on beards, and eventually drafting half a million serfs to build a city (named after himself) on nothing but marshland—he needed a robust bureaucracy and a standing military that could manage the demands of his new, spruced-up empire. Peter thus made service—civil or military—compulsory for the Russian nobility, and he implemented a new class system, the Table of Ranks, under which one could be promoted according to how long and how well one served.

The thing about big plans is that they require people to carry them out. The problem of personnel particularly plagued Peter the Great. Convinced by his European advisers that his country was backward and stuck in a medieval mindset, he spent much of his reign on a series of modernizing initiatives intended to get Russia “caught up” with the West. To implement his reforms—which included establishing a navy, imposing a tax on beards, and eventually drafting half a million serfs to build a city (named after himself) on nothing but marshland—he needed a robust bureaucracy and a standing military that could manage the demands of his new, spruced-up empire. Peter thus made service—civil or military—compulsory for the Russian nobility, and he implemented a new class system, the Table of Ranks, under which one could be promoted according to how long and how well one served.