Arundhati Roy in The Guardian:

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he said.

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he said.

“Shamshan! Shamshan!” the mesmerised, adoring crowd echoed back. Perhaps he is happy now that the haunting image of the flames rising from the mass funerals in India’s cremation grounds is making the front page of international newspapers. And that all the kabristans and shamshans in his country are working properly, in direct proportion to the populations they cater for, and far beyond their capacities. “Can India, population 1.3 billion, be isolated?” the Washington Post asked rhetorically in a recent editorial about India’s unfolding catastrophe and the difficulty of containing new, fast-spreading Covid variants within national borders. “Not easily,” it replied. It’s unlikely this question was posed in quite the same way when the coronavirus was raging through the UK and Europe just a few months ago. But we in India have little right to take offence, given our prime minister’s words at the World Economic Forum in January this year.

Modi spoke at a time when people in Europe and the US were suffering through the peak of the second wave of the pandemic. He had not one word of sympathy to offer, only a long, gloating boast about India’s infrastructure and Covid-preparedness. I downloaded the speech because I fear that when history is rewritten by the Modi regime, as it soon will be, it might disappear, or become hard to find. Here are some priceless snippets:

“Friends, I have brought the message of confidence, positivity and hope from 1.3 billion Indians amid these times of apprehension … It was predicted that India would be the most affected country from corona all over the world. It was said that there would be a tsunami of corona infections in India, somebody said 700-800 million Indians would get infected while others said 2 million Indians would die.”

“Friends, it would not be advisable to judge India’s success with that of another country. In a country which is home to 18% of the world population, that country has saved humanity from a big disaster by containing corona effectively.”

Modi the magician takes a bow for saving humanity by containing the coronavirus effectively. Now that it turns out that he has not contained it, can we complain about being viewed as though we are radioactive?

More here. (Note: Thanks to Nazli Raza!)

Sometime in mid-2009

Sometime in mid-2009 An outbreak the size of India’s second wave, apparently fuelled by Covid-19 variants that appear to be more infectious than earlier strains, would have overwhelmed most public health systems – let alone one of the

An outbreak the size of India’s second wave, apparently fuelled by Covid-19 variants that appear to be more infectious than earlier strains, would have overwhelmed most public health systems – let alone one of the  TRUST THE SCIENCE, we’re told. Wear masks! Science says so! These injunctions are likely to induce a couple of reflex responses. On the one hand, saying that you are in favor of Science — I’ll keep it capitalized for now — is somewhat like saying that you are all for oxygen and cute puppies and pleasant strolls. It is so straightforward as to be anodyne. But then there is the counter-reflex, with the “pro-Science” mantra sounding like a liberal shibboleth, and the Republican Party (or its voters) cast as Those Who Don’t Trust Science. Recent

TRUST THE SCIENCE, we’re told. Wear masks! Science says so! These injunctions are likely to induce a couple of reflex responses. On the one hand, saying that you are in favor of Science — I’ll keep it capitalized for now — is somewhat like saying that you are all for oxygen and cute puppies and pleasant strolls. It is so straightforward as to be anodyne. But then there is the counter-reflex, with the “pro-Science” mantra sounding like a liberal shibboleth, and the Republican Party (or its voters) cast as Those Who Don’t Trust Science. Recent  Nearly every day while writing my new book,

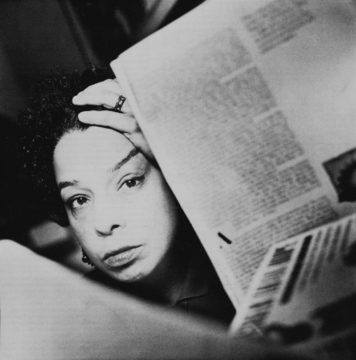

Nearly every day while writing my new book,  There are many reasons Mala’ika’s work has largely evaded the West. It’s hard to pigeonhole her, for one thing, which is by her own design. Mala’ika was always a neither-here-nor-there kind of poet. She was an Easterner with a calculated reverence for the West, a bard of Occidental impulses in a time and place more accustomed to Orientalist ones. She went from being a student of English poetry to being a scholar of it while simultaneously establishing herself as a thoroughly Arab poet. She was also an innovator whose free verse remains accessible while still keeping within her larger cultural tradition. And her feminism specifically concerned the roles of Arab women without evincing a need to compare, or center, the lives of her Western counterparts, as many women poets in her generation and beyond were tempted to do. (Mala’ika, with little fanfare, studied at Princeton in the 1950s, when it was still an all-male university.) She was also, finally, of the modernist and postmodernist eras but is perhaps best classified as a Romantic poet, despite publishing nearly a century after that movement’s heyday. As Drumsta notes in her substantial introduction, all these facts have perplexed Mala’ika’s biographers and translators.

There are many reasons Mala’ika’s work has largely evaded the West. It’s hard to pigeonhole her, for one thing, which is by her own design. Mala’ika was always a neither-here-nor-there kind of poet. She was an Easterner with a calculated reverence for the West, a bard of Occidental impulses in a time and place more accustomed to Orientalist ones. She went from being a student of English poetry to being a scholar of it while simultaneously establishing herself as a thoroughly Arab poet. She was also an innovator whose free verse remains accessible while still keeping within her larger cultural tradition. And her feminism specifically concerned the roles of Arab women without evincing a need to compare, or center, the lives of her Western counterparts, as many women poets in her generation and beyond were tempted to do. (Mala’ika, with little fanfare, studied at Princeton in the 1950s, when it was still an all-male university.) She was also, finally, of the modernist and postmodernist eras but is perhaps best classified as a Romantic poet, despite publishing nearly a century after that movement’s heyday. As Drumsta notes in her substantial introduction, all these facts have perplexed Mala’ika’s biographers and translators. Nothing but the Music, which collects verse written between 1974 and 1992, reasserts Davis’s centrality to the Black Arts and Black Feminist movements. Though the book covers a wide range of topics, all the poems engage with music: listening to it, composing it, being transformed by it. There are accounts of driving through a rainstorm to see the Commodores, descriptions of Senegalese seamstresses listening to jazz as they work, and visions of enslaved people singing during the Middle Passage. Davis employs a variety of stanza forms, though most of the poems are on the shorter side. “Many of these poems here were performed with a number of musicians in different improvising configurations,” she writes in the acknowledgments. Her collaborators include her late husband and composer Joseph Jarman, free jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor, and saxophonist Arthur Blythe.

Nothing but the Music, which collects verse written between 1974 and 1992, reasserts Davis’s centrality to the Black Arts and Black Feminist movements. Though the book covers a wide range of topics, all the poems engage with music: listening to it, composing it, being transformed by it. There are accounts of driving through a rainstorm to see the Commodores, descriptions of Senegalese seamstresses listening to jazz as they work, and visions of enslaved people singing during the Middle Passage. Davis employs a variety of stanza forms, though most of the poems are on the shorter side. “Many of these poems here were performed with a number of musicians in different improvising configurations,” she writes in the acknowledgments. Her collaborators include her late husband and composer Joseph Jarman, free jazz pioneer Cecil Taylor, and saxophonist Arthur Blythe.

Coming on the heels of

Coming on the heels of  James Carville: You ever get the sense that people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges use a different language than ordinary people? They come up with a word like

James Carville: You ever get the sense that people in faculty lounges in fancy colleges use a different language than ordinary people? They come up with a word like

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he

During a particularly polarising election campaign in the state of Uttar Pradesh in 2017, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, waded into the fray to stir things up even further. From a public podium, he accused the state government – which was led by an opposition party – of pandering to the Muslim community by spending more on Muslim graveyards (kabristans) than on Hindu cremation grounds (shamshans). With his customary braying sneer, in which every taunt and barb rises to a high note mid-sentence before it falls away in a menacing echo, he stirred up the crowd. “If a kabristan is built in a village, a shamshan should also be constructed there,” he  As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong.

As he later told the story in Kon-Tiki: Across the Pacific by Raft, he was brushed off by many in the scientific establishment — and so went to extraordinary lengths to prove the theory’s plausibility, reconstructing the ancient journey by sailing across the sea on a wooden raft in 1947. This spectacular feat captured the imagination of the world, and researchers, skeptical as they might have been, have ever since debated what really had happened in prehistoric times between South America and Polynesia (the group of Pacific islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii). Most scientists never accepted the amateur anthropology in which Heyerdahl couched his theory, but the mystery of an ancient trans-Pacific journey was a live one. All sorts of evidence would be marshalled, sometimes seeming to affirm Heyerdahl in part, sometimes seeming to show him entirely wrong. Milman Parry was arguably the most important American classical scholar of the 20th century, by one reckoning “the Darwin of Homeric Studies.” At age 26, this young man from California stepped into the world of Continental philologists and overturned some of their most deeply cherished notions of ancient literature. Homer, Parry showed, was no “writer” at all. The

Milman Parry was arguably the most important American classical scholar of the 20th century, by one reckoning “the Darwin of Homeric Studies.” At age 26, this young man from California stepped into the world of Continental philologists and overturned some of their most deeply cherished notions of ancient literature. Homer, Parry showed, was no “writer” at all. The