Month: February 2021

Is Depression A Uniquely Western Affliction?

Casey Schwartz at Bookforum:

This is the familiar arc that Jonathan Sadowsky traces in his new book The Empire of Depression: A New History. But Sadowsky, a medical historian at Case Western, aims to show how the Western notion of depression is making its way around the globe, threatening to displace other conceptions of the disease. “Western psychiatry often treats anxiety and depression as separate things that often occur together. In many places, though, anxiety and depression are seen as part of one thing,” he writes. And the sense of what causes depression differs significantly, too. Whereas in the West, depression is most often understood as having a physical reason, be it genes, or chemistry, “globally, it is more common to consider depression to be at once psychological, social, and physical.”

This is the familiar arc that Jonathan Sadowsky traces in his new book The Empire of Depression: A New History. But Sadowsky, a medical historian at Case Western, aims to show how the Western notion of depression is making its way around the globe, threatening to displace other conceptions of the disease. “Western psychiatry often treats anxiety and depression as separate things that often occur together. In many places, though, anxiety and depression are seen as part of one thing,” he writes. And the sense of what causes depression differs significantly, too. Whereas in the West, depression is most often understood as having a physical reason, be it genes, or chemistry, “globally, it is more common to consider depression to be at once psychological, social, and physical.”

The Western model even threatens to stomp out others’ subjective experiences. Sadowsky points to the Punjabi idiom, “sinking heart,” a condition which overlaps with depression, but is not quite identical to it.

more here.

The Machine Stops: Science and Its Limits

Henry M. Cowles at the LARB:

“IMAGINE, IF YOU CAN, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee.” So begins a story by E. M. Forster from over a century ago, about a future that feels uncannily like our present. Called “The Machine Stops,” the story conjures a world of individual humans isolated in such rooms who pass the time by streaming lectures and videoconferencing as the titular Machine tends to their every need. It is a world in which everything — music, food, even your bed — is summoned by the click of a button. In place of work, the Machine offers material and intellectual sustenance. For the story’s main character, Vashti, it turns life into a reassuringly predictable cycle: “[S]he made the room dark and slept; she awoke and made the room light; she ate and exchanged ideas with her friends, and listened to music and attended lectures; she made the room dark and slept. Above her, beneath her, and around her, the Machine hummed eternally.” To Vashti, the Machine offers serenity and certainty in equal measure. In this imagined world of isolated togetherness, heaven is a place.

“IMAGINE, IF YOU CAN, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee.” So begins a story by E. M. Forster from over a century ago, about a future that feels uncannily like our present. Called “The Machine Stops,” the story conjures a world of individual humans isolated in such rooms who pass the time by streaming lectures and videoconferencing as the titular Machine tends to their every need. It is a world in which everything — music, food, even your bed — is summoned by the click of a button. In place of work, the Machine offers material and intellectual sustenance. For the story’s main character, Vashti, it turns life into a reassuringly predictable cycle: “[S]he made the room dark and slept; she awoke and made the room light; she ate and exchanged ideas with her friends, and listened to music and attended lectures; she made the room dark and slept. Above her, beneath her, and around her, the Machine hummed eternally.” To Vashti, the Machine offers serenity and certainty in equal measure. In this imagined world of isolated togetherness, heaven is a place.

more here.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies at 101

Jesse McKinley in the New York Times:

The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.)

The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.)

While older and not a practitioner of their freewheeling personal style, Mr. Ferlinghetti befriended, published and championed many of the major Beat poets, among them Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Michael McClure. His connection to their work was exemplified — and cemented — in 1956 with his publication of Ginsberg’s most famous poem, the ribald and revolutionary “Howl,” an act that led to Mr. Ferlinghetti’s arrest on charges of “willfully and lewdly” printing “indecent writings.”

More here.

Ancient kauri trees capture last collapse of Earth’s magnetic field

Paul Voosen in Science:

Several years ago, workers breaking ground for a power plant in New Zealand unearthed a record of a lost time: a 60-ton trunk from a kauri tree, the largest tree species in New Zealand. The tree, which grew 42,000 years ago, was preserved in a bog and its rings spanned 1700 years, capturing a tumultuous time when the world was turned upside down—at least magnetically speaking.

Several years ago, workers breaking ground for a power plant in New Zealand unearthed a record of a lost time: a 60-ton trunk from a kauri tree, the largest tree species in New Zealand. The tree, which grew 42,000 years ago, was preserved in a bog and its rings spanned 1700 years, capturing a tumultuous time when the world was turned upside down—at least magnetically speaking.

Radiocarbon levels in this and several other pieces of wood chart a surge in radiation from space, as Earth’s protective magnetic field weakened and its poles flipped, a team of scientists reports today in Science. By modeling the effect of this radiation on the atmosphere, the team suggests Earth’s climate briefly shifted, perhaps contributing to the disappearance of large mammals in Australia and Neanderthals in Europe.

More here.

Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb discusses her book “Epidemic Empire” with Gauri Viswanathan

The great demographic reversal and what it means for the economy

Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan in the LSE Business Review:

The rise of China to the status of economic superpower has been the dominant narrative of the last three decades. China’s rise as the main feature of globalisation, in conjunction with a beneficial sweet spot in demography, drove output up and inflation down in the advanced economies. But these trends are now reversing. China’s economic success depended on many factors, a strong historical social and cultural background, political single-mindedness, a flexible and competent labour force, fed by internal migration, capital controls, developing satisfactory infrastructure and absorption of Western technological know-how. But China’s greatest contribution to global growth is now past. Its working age population is now shrinking, while the ranks of the old expands.

The rise of China to the status of economic superpower has been the dominant narrative of the last three decades. China’s rise as the main feature of globalisation, in conjunction with a beneficial sweet spot in demography, drove output up and inflation down in the advanced economies. But these trends are now reversing. China’s economic success depended on many factors, a strong historical social and cultural background, political single-mindedness, a flexible and competent labour force, fed by internal migration, capital controls, developing satisfactory infrastructure and absorption of Western technological know-how. But China’s greatest contribution to global growth is now past. Its working age population is now shrinking, while the ranks of the old expands.

This great demographic reversal will lead to a return of inflation, higher nominal interest rates, lessening inequality and higher productivity, but worsening fiscal problems, as medical, care and pension expenditures all increase in our ageing societies. Below are key points in our new book.the executive summaries of some of its chapters.

More here.

People Answer Scientists’ Queries in Real Time while Dreaming

Diana Kwon in Scientific American:

Dreams are full of possibilities; by drifting into the world beyond our waking realities, we can visit magical lands, travel through time and interact with long-lost family and friends. The notion of communicating in real time with someone outside of our dreamscapes, however, sounds like science fiction. A new study demonstrates that, to some extent, this seeming fantasy can be made real. Scientists already knew that one-way contact is attainable. Previous studies have demonstrated that people can process external cues, such as sounds and smells, while asleep. There is also evidence that people are able to send messages in the other direction: Lucid dreamers—those who can become aware they are in a dream—can be trained to signal, using eye movements, that they are in the midst of a dream. Two-way communication, however, is more complex. It requires a person who is asleep to actually understand what they hear from the outside and think about it logically enough to generate an answer, explains Ken Paller, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern University. “We believed that it was going to be possible—but until we actually demonstrated it, we weren’t sure.”

Dreams are full of possibilities; by drifting into the world beyond our waking realities, we can visit magical lands, travel through time and interact with long-lost family and friends. The notion of communicating in real time with someone outside of our dreamscapes, however, sounds like science fiction. A new study demonstrates that, to some extent, this seeming fantasy can be made real. Scientists already knew that one-way contact is attainable. Previous studies have demonstrated that people can process external cues, such as sounds and smells, while asleep. There is also evidence that people are able to send messages in the other direction: Lucid dreamers—those who can become aware they are in a dream—can be trained to signal, using eye movements, that they are in the midst of a dream. Two-way communication, however, is more complex. It requires a person who is asleep to actually understand what they hear from the outside and think about it logically enough to generate an answer, explains Ken Paller, a cognitive neuroscientist at Northwestern University. “We believed that it was going to be possible—but until we actually demonstrated it, we weren’t sure.”

For this study, Paller and his colleagues recruited volunteers who said they remembered at least one dream per week and provided them with guidance on how to lucid dream. They were also trained to respond to simple math problems by moving their eyes back and forth—for example, the correct answer to “eight minus six,” would be moving your eyes to the left and right twice. While the participants slept, electrodes attached to their faces picked up their eye movements and electroencephalography (EEG)—a method of monitoring brain activity—kept track of what stage of sleep they were in.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Poetry as Insurgent Art

[I am signaling you through the flames]

I am signaling you through the flames.

The North Pole is not where it used to be.

Manifest Destiny is no longer manifest.

Civilization self-destructs.

Nemesis is knocking at the door.

What are poets for, in such an age?

What is the use of poetry?

The state of the world calls out for poetry to save it.

If you would be a poet, create works capable of answering the

challenge of apocalyptic times, even if this meaning sounds

apocalyptic.

You are Whitman, you are Poe, you are Mark Twain, you are

Emily Dickinson and Edna St. Vincent Millay, you are Neruda

and Mayakovsky and Pasolini, you are an American or a non-

American, you can conquer the conquerors with words….

by Lawrence Ferlinghetti – 1919-Feb.2021

from Poetry as Insurgent Art

New Directions, 2007

‘The Sum of Us’ Tallies the Cost of Racism for Everyone

Jennifer Szalai in The New York Times:

Hinton Rowan Helper was an unreserved bigot from North Carolina who wrote hateful, racist tracts during Reconstruction. He was also, in the years leading up to the Civil War, a determined abolitionist.

Hinton Rowan Helper was an unreserved bigot from North Carolina who wrote hateful, racist tracts during Reconstruction. He was also, in the years leading up to the Civil War, a determined abolitionist.

His 1857 book, “The Impending Crisis of the South,” argued that chattel slavery had deformed the Southern economy and impoverished the region. Members of the plantation class refused to invest in education, in enterprise, in the community at large, because they didn’t have to. Helper’s concern wasn’t the enslaved Black people brutalized by what he called the “lords of the lash”; he was worried about the white laborers in the South, relegated by the slave economy and its ruling oligarchs to a “cesspool of ignorance and degradation.” Helper and his argument come up early on in Heather McGhee’s illuminating and hopeful new book, “The Sum of Us” — though McGhee, a descendant of enslaved people, is very much concerned with the situation of Black Americans, making clear that the primary victims of racism are the people of color who are subjected to it. But “The Sum of Us” is predicated on the idea that little will change until white people realize what racism has cost them too. The material legacy of slavery can be felt to this day, McGhee says, in depressed wages and scarce access to health care in the former Confederacy. But it’s a blight that’s no longer relegated to the region. “To a large degree,” she writes, “the story of the hollowing out of the American working class is a story of the Southern economy, with its deep legacy of exploitative labor and divide-and-conquer tactics, going national.”

As the pandemic has laid bare, the United States is a rich country that also happens to be one of the stingiest when it comes to the welfare of its own people. McGhee, who spent years working on economic policy for Demos, a liberal think tank, says it was the election of Donald Trump in 2016 by a majority of white voters that made her realize how most white voters weren’t “operating in their own rational economic self-interest.” Despite Trump’s populist noises, she writes, his agenda “promised to wreak economic, social and environmental havoc on them along with everyone else.”

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)

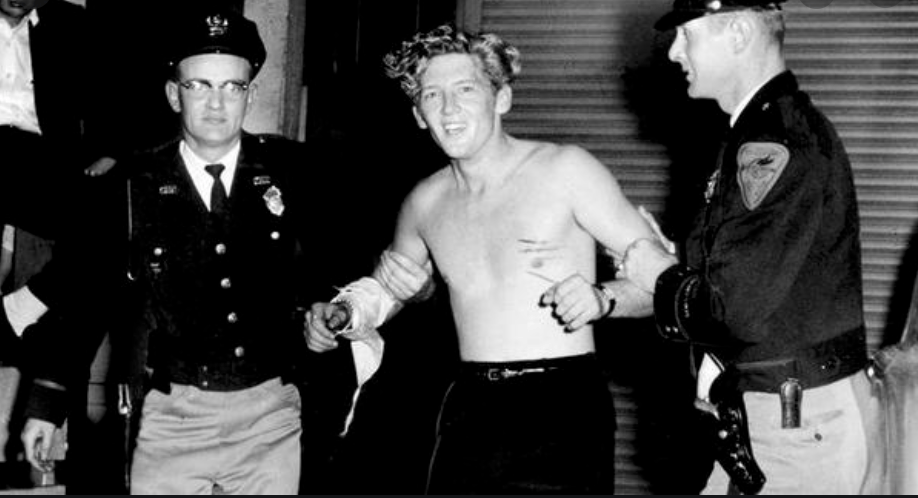

On Eminem and Late Style

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Study, reader, before going further, this sonic document: a recording of Jerry Lee Lewis performing “Mean Woman Blues”, with the Nashville Teens (of Surrey) backing him up, at the Star Club of Hamburg, on the night of April 5, 1964. Not when Hendrix immolated his guitar in Monterey, not when Ozzy decapitated a bat in Des Moines: never did rock and roll more fully realize its evil potential.

Study, reader, before going further, this sonic document: a recording of Jerry Lee Lewis performing “Mean Woman Blues”, with the Nashville Teens (of Surrey) backing him up, at the Star Club of Hamburg, on the night of April 5, 1964. Not when Hendrix immolated his guitar in Monterey, not when Ozzy decapitated a bat in Des Moines: never did rock and roll more fully realize its evil potential.

Much could be said about the confluence of circumstances that made this possible. Lewis was already old at 29, a relic of the 1950s, playing a dated and proto-normie boogie-woogie routine in a city that had recently incubated and then delivered into the world his far more lovable successors — the “Liverpudlian mop-tops”, along with all the other diminutive epithets the press came up with for the Beatles, always more suited to newborn zoo animals than to men.

He was, moreover, still in de-facto exile. The scandal of a marriage (to the extent that we can call it that) in 1957 to his own thirteen-year-old cousin Myra Gale Brown led the American public to conclude that, because his moral person was beyond the pale, his music was therefore unlistenable. In Europe it is not that morality and aesthetics were decoupled, exactly, but rather that their intertwining led to the opposite conclusion: the Germans wanted to hear him not in spite of the fact that he was a psychotic hillbilly, but because of it, and Jerry Lee knew how to summon all the satanic energy of his life and of his nation to satisfy them.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Shadi Bartsch on Plato, Vergil, Confucius, and Modernity

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

In our postmodern world, studying the classics of ancient Greece and Rome can seem quaint at best, downright repressive at worst. (We are talking about works by dead white men, after all.) Do we still have things to learn from classical philosophy, drama, and poetry? Shadi Bartsch offers a vigorous affirmative to this question in two new books coming from different directions. First, she has newly translated the Aeneid, Vergil’s epic poem about the founding myth of Rome, bringing its themes into conversation with the modern era. Second, in the upcoming Plato Goes to China, she explores how a non-Western society interprets classic works of Western philosophy, and what that tells us about each culture.

In our postmodern world, studying the classics of ancient Greece and Rome can seem quaint at best, downright repressive at worst. (We are talking about works by dead white men, after all.) Do we still have things to learn from classical philosophy, drama, and poetry? Shadi Bartsch offers a vigorous affirmative to this question in two new books coming from different directions. First, she has newly translated the Aeneid, Vergil’s epic poem about the founding myth of Rome, bringing its themes into conversation with the modern era. Second, in the upcoming Plato Goes to China, she explores how a non-Western society interprets classic works of Western philosophy, and what that tells us about each culture.

More here.

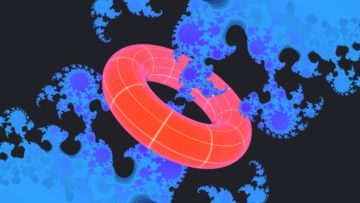

A new proof demonstrates the power of arithmetic dynamics

Kelsey Houston-Edwards in Quanta:

Joseph Silverman remembers when he began connecting the dots that would ultimately lead to a new branch of mathematics: April 25, 1992, at a conference at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

Joseph Silverman remembers when he began connecting the dots that would ultimately lead to a new branch of mathematics: April 25, 1992, at a conference at Union College in Schenectady, New York.

It happened by accident while he was at a talk by the decorated mathematician John Milnor. Milnor’s subject was a field called complex dynamics, which Silverman knew little about. But as Milnor introduced some basic ideas, Silverman started to see a striking resemblance to the field of number theory where he was an expert.

“If you just change a couple of the words, there’s an analogous sort of problem,” he remembers thinking to himself.

Silverman, a mathematician at Brown University, left the room inspired. He asked Milnor some follow-up questions over breakfast the next day and then set to work pursuing the analogy. His goal was to create a dictionary that would translate between dynamical systems and number theory.

More here.

Al Gore and John Kerry on the US being back in the Paris Agreement

Woke Me When It’s Over

Bret Stephens in the New York Times:

In 2015, Bon Appétit ran an article by the food writer Dawn Perry about hamantaschen, the triangular cookies that are a tradition during the Jewish festival of Purim. It was headlined — brace yourself for outrage — “How to Make Actually Good Hamantaschen.”

In 2015, Bon Appétit ran an article by the food writer Dawn Perry about hamantaschen, the triangular cookies that are a tradition during the Jewish festival of Purim. It was headlined — brace yourself for outrage — “How to Make Actually Good Hamantaschen.”

Six years later, a woman named Abigail Koffler found the article while researching hamantaschen fillings. She was not amused.

Perry, Koffler wrote on Twitter, isn’t Jewish. Perry’s husband, Koffler added, had been forced out of his job at Condé Nast last year based on accusations of racial bias. Above all, Koffler objected, “Traditional foods do not automatically need to be updated, especially by someone who does not come from that tradition.”

More here.

Martin Heidegger Interview With A Monk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcsBtl1SwuY&ab_channel=PhilosophyOverdose

Josh Cohen On Literature And Psychoanalysis

Leo Robson at The New Statesman:

Much of Cohen’s work is driven by his aversion to a type of spatial metaphor that minimises the value and variety of familiar experience. His first book, Spectacular Allegories (1998), a study of modern American fiction and journalism that emerged from his PhD, questions the postmodern idea that spectacle somehow floats “outside” history and “above” material reality. It was written before Cohen was a practitioner, or even employed Freudian theory. He told me that his “obsessional preoccupation – and I’m pointedly using the singular – has been what is concealed in what is right in front of us, in what is present”. He isn’t only talking about unconscious blind-spots. The book’s title is “filched”, as he puts it, from the American poet Wallace Stevens, and Cohen expressed a particular fondness for Stevens’s idea of a “strange presence that irradiates through the world that his poems are always gesturing towards and trying to get us to see”.

Much of Cohen’s work is driven by his aversion to a type of spatial metaphor that minimises the value and variety of familiar experience. His first book, Spectacular Allegories (1998), a study of modern American fiction and journalism that emerged from his PhD, questions the postmodern idea that spectacle somehow floats “outside” history and “above” material reality. It was written before Cohen was a practitioner, or even employed Freudian theory. He told me that his “obsessional preoccupation – and I’m pointedly using the singular – has been what is concealed in what is right in front of us, in what is present”. He isn’t only talking about unconscious blind-spots. The book’s title is “filched”, as he puts it, from the American poet Wallace Stevens, and Cohen expressed a particular fondness for Stevens’s idea of a “strange presence that irradiates through the world that his poems are always gesturing towards and trying to get us to see”.

more here.

Why Keats’s haunting reflections on tuberculosis resonate in the age of Covid-19

Michael Barrett in New Stateman:

We knew that the persistent cough spelled his end. The fever had preceded it, just as it had in his mother, brother and dozens around him. The contagion that was devastating society had him in its throes. When he finally died, a postmortem showed his lungs had been decimated. He’d suffocated, drowning in his own inflammatory fluids. The young English poet John Keats died aged just 25 in Rome on 23 February 1821, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, or consumption as it was then known, just over a year before. In 1819, inspired by his medical training and acute observation of his disease, Keats captured the essence of its impact on society.

We knew that the persistent cough spelled his end. The fever had preceded it, just as it had in his mother, brother and dozens around him. The contagion that was devastating society had him in its throes. When he finally died, a postmortem showed his lungs had been decimated. He’d suffocated, drowning in his own inflammatory fluids. The young English poet John Keats died aged just 25 in Rome on 23 February 1821, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, or consumption as it was then known, just over a year before. In 1819, inspired by his medical training and acute observation of his disease, Keats captured the essence of its impact on society.

“Ode to a Nightingale” (1819), written as his symptoms took hold, speaks of “the weariness, the fever and the fret” associated with his condition where “youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies; where but to think is to be full of sorrow and leaden-eyed despairs”, and where the “the dull brain perplexes and retards”. He envies the nightingale, free from disease and able to fly through the woodland skies, while Keats wishes to alleviate his suffering through death: “for many a time I have been half in love with easeful Death, Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme, To take into the air my quiet breath; Now more than ever seems it rich to die, To cease upon the midnight with no pain, While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad In such an ecstasy!”

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Nike

The young woman who settles beside me on the bench along the running track

wears a shirt labeled Nike over one sweat-stained breast.

She is probably oblivious to the goddess who personified victory.

It is very unlikely that she is also a daughter of the Titan Pallas and the goddess Styx.

But as her essence evaporates into my nostrils, I wonder –

Are those goddess pheromones

that are making me accidentally-on-purpose

move my arm closer until it touches her arm

and causing her to follicle fan me

when she pulls back her long hair

and rearranges it with a circle

of metal leaves that might be laurel?

When she stands, the Sun helmets her blonde head

I want to follow her

as she continues to fly around the field

rewarding the victors with glory and fame,

but my mortal rules won’t allow that.

by Lily Hayashi

from Poets Online

How a mass suicide by slaves caused the legend of the flying African to take off

From The Conversation:

In May 1803 a group of enslaved Africans from present-day Nigeria, of Ebo or Igbo descent, leaped from a single-masted ship into Dunbar Creek off St. Simons Island in Georgia. A slave agent concluded that the Africans drowned and died in an apparent mass suicide. But oral traditions would go on to claim that the Eboes either flew or walked over water back to Africa.

In May 1803 a group of enslaved Africans from present-day Nigeria, of Ebo or Igbo descent, leaped from a single-masted ship into Dunbar Creek off St. Simons Island in Georgia. A slave agent concluded that the Africans drowned and died in an apparent mass suicide. But oral traditions would go on to claim that the Eboes either flew or walked over water back to Africa.

For generations, island residents, known as the Gullah-Geechee people, passed down the tale. When folklorists arrived in the 1930s, Igbo Landing and the story of the flying African assumed a mythological place in African American culture. Though the site carries no bronze plaque and remains unmarked on tourist maps, it has become a symbol of the traumatizing legacy of trans-Atlantic slavery. Poets, artists, filmmakers, jazz musicians, griots, novelists such as Toni Morrison and pop stars like Beyoncé have all told versions of the tale. They’ll often switch up the story’s details to reflect different times and places. Yet the heart of the original tale, one of longing for freedom, beats through each of these retellings. The stories continue to resonate because those yearnings – whether they’re from the cargo hold of a sloop or the confines of a prison cell – remain just as intense today.

As an academic trained in literary history, I always look for the reasons behind a story’s origins, and how stories travel or change over time. Variations of the flying African myth have been recorded from Arkansas to Canada, Cuba and Brazil. Yet even as the many versions cut across the Black diaspora, the legend has coalesced around a single place: St. Simons. An entry in the Georgia Encyclopedia makes a direct correlation between the 1803 rebellion mass suicide and the later, literary folkloric tradition.

Why? One reason is geographic.

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)