Rachel Cooke in The Guardian:

You may not have heard of Robin Dunbar. But you will, perhaps, know of his work. Dunbar, now emeritus professor of evolutionary psychology at Oxford University, is the man who first suggested that there may be a cognitive limit to the number of people with whom you can comfortably maintain stable social relationships – or, as Stephen Fry put it on the TV show QI, the number of people “you would not hesitate to go and sit with if you happened to see them at 3am in the departure lounge at Hong Kong airport”. Human beings, Dunbar found when he conducted his research in the 1990s, typically have 150 friends in general (people who know us on sight, and with whom we have a history), of whom just five can usually be described as intimate.

You may not have heard of Robin Dunbar. But you will, perhaps, know of his work. Dunbar, now emeritus professor of evolutionary psychology at Oxford University, is the man who first suggested that there may be a cognitive limit to the number of people with whom you can comfortably maintain stable social relationships – or, as Stephen Fry put it on the TV show QI, the number of people “you would not hesitate to go and sit with if you happened to see them at 3am in the departure lounge at Hong Kong airport”. Human beings, Dunbar found when he conducted his research in the 1990s, typically have 150 friends in general (people who know us on sight, and with whom we have a history), of whom just five can usually be described as intimate.

In his new book, Dunbar revisits and unpicks this number, by which he stands; and he brings together several decades of other research in the area of friendship, some of it his own, some that of anthropologists, geneticists and neuroscientists with whom he has worked. It can’t be definitive: the possibilities in this field are surely limitless. But for the reader, it sometimes feels like it is. Why do most women have a best friend? Why do many men struggle to share confidences? Why is it so painful when we fall out with our friends? Above all, what effect do friends (or a lack of them) have on our mental and physical health? Think of any question you might have and you’ll find some kind of an answer to it here. What you may feel in your gut, it will back with science. Its central message, however, may be summed up in a sentence. In essence, the number and quality of our friendships may have a bigger influence on our happiness, health and mortality risk than anything else in life save for giving up smoking.

More here.

No one has played a greater role in helping all Americans know the black past than Carter G. Woodson, the individual who created Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in February 1926. Woodson was the second black American to receive a PhD in history from Harvard—following W.E.B. Du Bois by a few years. To Woodson, the black experience was too important simply to be left to a small group of academics. Woodson believed that his role was to use black history and culture as a weapon in the struggle for racial uplift. By 1916, Woodson had moved to DC and established the “Association for the Study of Negro Life and Culture,” an organization whose goal was to make black history accessible to a wider audience. Woodson was a strange and driven man whose only passion was history, and he expected everyone to share his passion.

No one has played a greater role in helping all Americans know the black past than Carter G. Woodson, the individual who created Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in February 1926. Woodson was the second black American to receive a PhD in history from Harvard—following W.E.B. Du Bois by a few years. To Woodson, the black experience was too important simply to be left to a small group of academics. Woodson believed that his role was to use black history and culture as a weapon in the struggle for racial uplift. By 1916, Woodson had moved to DC and established the “Association for the Study of Negro Life and Culture,” an organization whose goal was to make black history accessible to a wider audience. Woodson was a strange and driven man whose only passion was history, and he expected everyone to share his passion. Robert Hockett over at the New Labor Forum:

Robert Hockett over at the New Labor Forum: Ravinder Kaur in Aeon:

Ravinder Kaur in Aeon: Danielle Allen in The Atlantic:

Danielle Allen in The Atlantic:

This timely republication of Bessie Smith, with a new introduction extolling hercontinued relevance, charts some of the distance travelled both by the publishing industry and by Kay herself, now Scotland’s

This timely republication of Bessie Smith, with a new introduction extolling hercontinued relevance, charts some of the distance travelled both by the publishing industry and by Kay herself, now Scotland’s  “Fierce Poise” focuses on the artist in an unconventional way: It covers the years 1950-60 in 11 chapters, each jumping off a specific date during one of those years. The resulting book is lively but short, skimming the surface of Frankenthaler’s work. Nemerov calls this choice “true to Helen” in that “the singularity of a day offers me an unscientific precision — a fluid glimpse into a moment — like Helen’s own.” The conceit is that the early days capture the essence of her work, but the constraint only shortchanges her contested legacy by eliding the rest of her long career.

“Fierce Poise” focuses on the artist in an unconventional way: It covers the years 1950-60 in 11 chapters, each jumping off a specific date during one of those years. The resulting book is lively but short, skimming the surface of Frankenthaler’s work. Nemerov calls this choice “true to Helen” in that “the singularity of a day offers me an unscientific precision — a fluid glimpse into a moment — like Helen’s own.” The conceit is that the early days capture the essence of her work, but the constraint only shortchanges her contested legacy by eliding the rest of her long career. February 18, 2021 would have been

February 18, 2021 would have been  For the Ishiguro household, 5 October 2017 was a big day. After weeks of discussion, the author’s wife, Lorna, had finally decided to change her hair colour. She was sitting in a Hampstead salon, not far from Golders Green in London, where they have lived for many years, all gowned up, and glanced at her phone. There was a news flash. “I’m sorry, I’m going to have to stop this,” she said to the waiting hairdresser. “My husband has just won the Nobel prize for literature. I might have to help him out.”

For the Ishiguro household, 5 October 2017 was a big day. After weeks of discussion, the author’s wife, Lorna, had finally decided to change her hair colour. She was sitting in a Hampstead salon, not far from Golders Green in London, where they have lived for many years, all gowned up, and glanced at her phone. There was a news flash. “I’m sorry, I’m going to have to stop this,” she said to the waiting hairdresser. “My husband has just won the Nobel prize for literature. I might have to help him out.” For a critic, there’s maybe nothing so central but also confounding as the question of taste — why we like what we like, and whether it’s something we decide for ourselves, based purely on our own freedom and idiosyncracies; or if our tastes can be shaped and even scripted, influenced by earnest argument, entrenched biases or cynical manipulation.

For a critic, there’s maybe nothing so central but also confounding as the question of taste — why we like what we like, and whether it’s something we decide for ourselves, based purely on our own freedom and idiosyncracies; or if our tastes can be shaped and even scripted, influenced by earnest argument, entrenched biases or cynical manipulation. 1. Always refer to Iran as the “Islamic Republic” and its government as “the regime” or, better yet, “the Mullahs.”

1. Always refer to Iran as the “Islamic Republic” and its government as “the regime” or, better yet, “the Mullahs.”

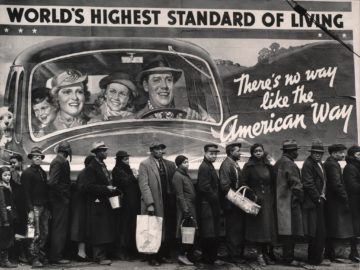

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study

The anti-government stinginess of traditional conservatism, along with the fear of losing social status held by many white people, now broadly associated with Trumpism, have long been connected. Both have sapped American society’s strength for generations, causing a majority of white Americans to rally behind the draining of public resources and investments. Those very investments would provide white Americans — the largest group of the impoverished and uninsured — greater security, too: A new Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study  I grew up in one of those small Palestinian villages where some of Nimr’s readership likely stems from, quite close to where Nimr teaches. I read plenty of kid-lit on my way to school (and at school when I was supposed to be paying attention); I went on adventures with dragons and later, I traveled into deep space. I could have used a heroine like Qamar when I was younger to encourage me to step outside of my own reality. Not only does she look like me, Qamar feels written for me. I see much of my upbringing in Qamar, in how I approach rest, play, work, and curiosity, even perhaps how I approach being a woman. Qamar moves at her own pace, and while she is concerned with survival, she also understands how to adapt, when to let something bizarre and even unjust become normalized, and when that is no longer acceptable.

I grew up in one of those small Palestinian villages where some of Nimr’s readership likely stems from, quite close to where Nimr teaches. I read plenty of kid-lit on my way to school (and at school when I was supposed to be paying attention); I went on adventures with dragons and later, I traveled into deep space. I could have used a heroine like Qamar when I was younger to encourage me to step outside of my own reality. Not only does she look like me, Qamar feels written for me. I see much of my upbringing in Qamar, in how I approach rest, play, work, and curiosity, even perhaps how I approach being a woman. Qamar moves at her own pace, and while she is concerned with survival, she also understands how to adapt, when to let something bizarre and even unjust become normalized, and when that is no longer acceptable. We realize then that from the fantastic opening image of the sea whom the poet would like to invite in, like a good neighbor, to have a coffee, to the powerful ending of “All of It,” each line of Exhausted on the Cross is the scene of a physical fight, to the death, between words and what we can no longer say. We cannot express the tension of that centimeter that separates us from the woman from Shatila. There are no words to name the absolute horror, to account for the exact moment in which the body of a living child becomes the body of a slaughtered child, we lack images to fix that infinitesimal second in which someone becomes those lumps of flesh and bone thrown into the sea by Latin American dictators, or the heaps of scattered limbs of Palestinians crushed by Israeli bombs in Gaza, or those massacred in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. We have no concepts to imagine what questions, what memories assail someone in that monstrous extreme, someone being killed by other men. And yet, for that very reason, precisely because those words do not exist, they must be shouted, to bring to this side of the world the terrible and ruthless porosity of each of those moments.

We realize then that from the fantastic opening image of the sea whom the poet would like to invite in, like a good neighbor, to have a coffee, to the powerful ending of “All of It,” each line of Exhausted on the Cross is the scene of a physical fight, to the death, between words and what we can no longer say. We cannot express the tension of that centimeter that separates us from the woman from Shatila. There are no words to name the absolute horror, to account for the exact moment in which the body of a living child becomes the body of a slaughtered child, we lack images to fix that infinitesimal second in which someone becomes those lumps of flesh and bone thrown into the sea by Latin American dictators, or the heaps of scattered limbs of Palestinians crushed by Israeli bombs in Gaza, or those massacred in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. We have no concepts to imagine what questions, what memories assail someone in that monstrous extreme, someone being killed by other men. And yet, for that very reason, precisely because those words do not exist, they must be shouted, to bring to this side of the world the terrible and ruthless porosity of each of those moments.