Month: February 2021

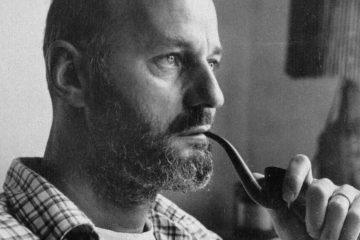

Thank You, Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Alysia Abbott at Literary Hub:

When Lawrence Ferlinghetti died this week at age 101, nearly one month shy his 102nd birthday, many of my friends, even writer friends, expressed surprise on social media. I didn’t even know he was still alive!

Indeed, Ferlinghetti outlived all the younger Beat writers he once published including Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Greg Corso. When The New York Times, in a 2005 interview, asked him why, he answered, “Kerouac drank himself to death, and Burroughs, when he was young, thought the healthiest person was one who had enough money to stay on heroin all his life. I really never got into drugs. I smoked a little dope, and I did a little LSD, but that was it. I was afraid of it, frankly. I don’t like to be out of control.”

But for me, and a segment of San Franciscans and aspiring bohemians worldwide, Ferlinghetti seemed immortal; we found comfort in this.

more here.

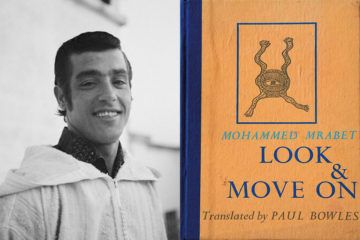

The Storyteller of Tangier

Lucy Scholes at The Paris Review:

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, everyone from Life magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic The Sheltering Sky. “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg among them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet.

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, everyone from Life magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic The Sheltering Sky. “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg among them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet.

more here.

What “weird Catholicism” reveals about the language of the internet

Justin E. H. Smith in the New Statesman:

When the New York Times Magazine ran its profile of the “Weird Catholic Twitter” (WCT) community in May 2020, extremely-online Catholics and non-Catholics alike came together in one of the internet’s periodic gestures of widespread, synchronised eye-rolling. One well-known Twitter personality, Connor Wroe Southard, wrote that this exposé was akin to the same newspaper’s description of the alt-right YouTuber Ben Shapiro as “the cool kid’s philosopher”. Another familiar voice of Twitter, Liz Franczak, exclaimed in a rawer spirit: “I cannot believe there is a Weird Catholic Twitter piece in nytmag.”

When the New York Times Magazine ran its profile of the “Weird Catholic Twitter” (WCT) community in May 2020, extremely-online Catholics and non-Catholics alike came together in one of the internet’s periodic gestures of widespread, synchronised eye-rolling. One well-known Twitter personality, Connor Wroe Southard, wrote that this exposé was akin to the same newspaper’s description of the alt-right YouTuber Ben Shapiro as “the cool kid’s philosopher”. Another familiar voice of Twitter, Liz Franczak, exclaimed in a rawer spirit: “I cannot believe there is a Weird Catholic Twitter piece in nytmag.”

The general consensus was that the NYT, as a vehicle of mainstream liberal ideology, was late to the scene, and was corrupting the nature of the thing it was seeking to report on for a larger audience, as has always happened when a subcultural trend gains mainstream attention. But the arrival of WCT in such a venue also brought to a wider public a familiar lesson: that in the era of social media no institution, not even the ones most defiantly removed from the shifting winds of fashion, can entirely avoid getting weird. Everything is getting weird, even the church built upon a rock.

My interest here is personal. I am Catholic, but in a weird and uncertain way.

More here.

Artificial Neural Nets Finally Yield Clues to How Brains Learn

Anil Ananthaswamy in Quanta:

In 2007, some of the leading thinkers behind deep neural networks organized an unofficial “satellite” meeting at the margins of a prestigious annual conference on artificial intelligence. The conference had rejected their request for an official workshop; deep neural nets were still a few years away from taking over AI. The bootleg meeting’s final speaker was Geoffrey Hinton of the University of Toronto, the cognitive psychologist and computer scientist responsible for some of the biggest breakthroughs in deep nets. He started with a quip: “So, about a year ago, I came home to dinner, and I said, ‘I think I finally figured out how the brain works,’ and my 15-year-old daughter said, ‘Oh, Daddy, not again.’”

In 2007, some of the leading thinkers behind deep neural networks organized an unofficial “satellite” meeting at the margins of a prestigious annual conference on artificial intelligence. The conference had rejected their request for an official workshop; deep neural nets were still a few years away from taking over AI. The bootleg meeting’s final speaker was Geoffrey Hinton of the University of Toronto, the cognitive psychologist and computer scientist responsible for some of the biggest breakthroughs in deep nets. He started with a quip: “So, about a year ago, I came home to dinner, and I said, ‘I think I finally figured out how the brain works,’ and my 15-year-old daughter said, ‘Oh, Daddy, not again.’”

The audience laughed. Hinton continued, “So, here’s how it works.” More laughter ensued.

Hinton’s jokes belied a serious pursuit: using AI to understand the brain. Today, deep nets rule AI in part because of an algorithm called backpropagation, or backprop. The algorithm enables deep nets to learn from data, endowing them with the ability to classify images, recognize speech, translate languages, make sense of road conditions for self-driving cars, and accomplish a host of other tasks.

More here.

Glenn Greenwald on Trending as a Transphobe and Biphobe

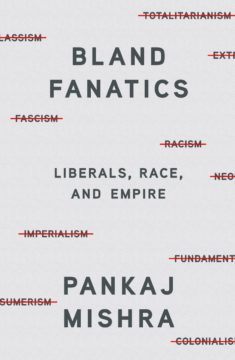

Pankaj Mishra’s Reckoning With Liberalism’s Bloody Past

Kanishk Tharoor in The New Republic:

For nearly three decades, Mishra has skewered the pieties of politicians and intellectuals in the Anglophone world (including India, which boasts more English speakers than the United Kingdom), while also bringing his spirited attention to the histories and imaginations of people outside circles of wealth and power. The scales first fell from his eyes during his travels and reporting in Kashmir in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the disputed Indian-administered territory, he saw firsthand the collision between India’s pluralist liberal democracy—its avowed commitment to democratic norms, individual rights, and multiculturalism—and the reality of military occupation. Indian apologia for abuses in Kashmir, he writes, “prepared me for the spectacle of a liberal intelligentsia cheerleading the war for ‘human rights’ in Iraq, with the kind of humanitarian rhetoric about freedom, democracy and progress that was originally heard from European imperialists in the nineteenth century.” The remit of Mishra’s work has grown steadily wider over the decades, from an early focus on the dreams and catastrophes of small-town India, to a thoughtful exploration of colonial-era Asian intellectual history in the excellent From the Ruins of Empire (2012), to the sweeping global jurisdiction of his recent books, which directly confront the international order made by the United Kingdom and the United States.

For nearly three decades, Mishra has skewered the pieties of politicians and intellectuals in the Anglophone world (including India, which boasts more English speakers than the United Kingdom), while also bringing his spirited attention to the histories and imaginations of people outside circles of wealth and power. The scales first fell from his eyes during his travels and reporting in Kashmir in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the disputed Indian-administered territory, he saw firsthand the collision between India’s pluralist liberal democracy—its avowed commitment to democratic norms, individual rights, and multiculturalism—and the reality of military occupation. Indian apologia for abuses in Kashmir, he writes, “prepared me for the spectacle of a liberal intelligentsia cheerleading the war for ‘human rights’ in Iraq, with the kind of humanitarian rhetoric about freedom, democracy and progress that was originally heard from European imperialists in the nineteenth century.” The remit of Mishra’s work has grown steadily wider over the decades, from an early focus on the dreams and catastrophes of small-town India, to a thoughtful exploration of colonial-era Asian intellectual history in the excellent From the Ruins of Empire (2012), to the sweeping global jurisdiction of his recent books, which directly confront the international order made by the United Kingdom and the United States.

More here.

Friday Poem

Self-Portrait

Between the computer, a pencil, and a typewriter

half my day passes. One day it will be half a century.

I live in strange cities and sometimes talk

with strangers about matters strange to me.

I listen to music a lot: Bach, Mahler, Chopin, Shostakovich.

I see three elements in music: weakness, power, and pain.

The fourth has no name.

I read poets, living and dead, who teach me

tenacity, faith, and pride. I try to understand

the great philosophers–but usually catch just

scraps of their precious thoughts.

I like to take long walks on Paris streets

and watch my fellow creatures, quickened by envy,

anger, desire; to trace a silver coin

passing from hand to hand as it slowly

loses its round shape (the emperor’s profile is erased).

Beside me trees expressing nothing

but a green, indifferent perfection.

Black birds pace the fields,

waiting patiently like Spanish widows.

I’m no longer young, but someone else is always older.

I like deep sleep, when I cease to exist,

and fast bike rides on country roads when poplars and houses

dissolve like cumuli on sunny days.

Sometimes in museums the paintings speak to me

and irony suddenly vanishes.

I love gazing at my wife’s face.

Every Sunday I call my father.

Every other week I meet with friends,

thus proving my fidelity.

My country freed itself from one evil. I wish

another liberation would follow.

Could I help in this? I don’t know.

I’m truly not a child of the ocean,

as Antonio Machado wrote about himself,

but a child of air, mint and cello

and not all the ways of the high world

cross paths with the life that–so far–

belongs to me.

by Adam Zagajewski

translated by Clare Cavanagh

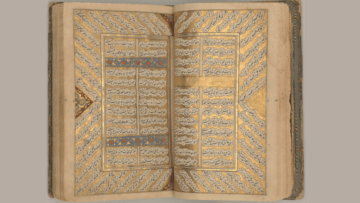

Between the Lines: Seeking solace in the work of the fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafez

Nilo Tabrizy in Guernica:

I wouldn’t wish being Iranian on my worst enemy,” my friend Marjan posted on Instagram in mid-January.

I wouldn’t wish being Iranian on my worst enemy,” my friend Marjan posted on Instagram in mid-January.

Like many Iranians, Marjan is stuck in visa limbo. An economics professor in New York, she traveled to Iran in August of last year, and by the time her return visa was finally issued, coronavirus restrictions meant she was stuck in Iran. But her post was about more than just travel frustrations. From individual experiences to our collective story, the past nine months have been a painful series of run-on tragedies for Iranians: November 2019 saw nation-wide demonstrations where state security forces killed 1,500 protesters. In January, the US government ordered a targeted killing of Iran’s top military general, and Iran responded with a missile strike on a US military base in Iraq. Days later, the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) downed a civilian airliner, killing 176 passengers and crewmembers in the midst of the escalated tension of war. And then in February, the coronavirus crisis. It’s been all-consuming. I cover Iran in video for the New York Times, and spent January tracking down and interviewing eyewitnesses in Iran who saw the plane crash, while dealing with the trauma of reporting on a story that impacted me deeply, as a member of the Iranian-Canadian community.

I was born in Tehran during the turbulent beginnings of the nascent Islamic Republic. Iran was rebuilding after the 1979 revolution, which ended centuries of monarchy and installed a then-popularly backed Islamic government. But the revolution was quickly followed by a brutal eight-year war with Iraq.

More here.

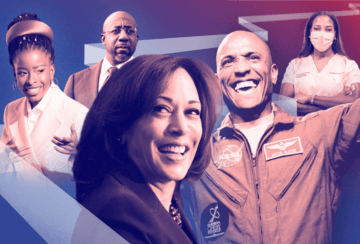

23 Black leaders who are shaping history today

Courtney Connley in Make it:

Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And since 1976, every U.S. president has designated the month of February as Black History Month to honor the achievements and the resilience of the Black community. While CNBC Make It recognizes that Black history is worth being celebrated year-round, we are using this February to shine a special spotlight on 23 Black leaders whose recent accomplishments and impact will inspire many generations to come. These leaders, who have made history in their respective fields, stand on the shoulders of pioneers who came before them, including Shirley Chisholm, John Lewis, Maya Angelou and Mary Ellen Pleasant.

Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And since 1976, every U.S. president has designated the month of February as Black History Month to honor the achievements and the resilience of the Black community. While CNBC Make It recognizes that Black history is worth being celebrated year-round, we are using this February to shine a special spotlight on 23 Black leaders whose recent accomplishments and impact will inspire many generations to come. These leaders, who have made history in their respective fields, stand on the shoulders of pioneers who came before them, including Shirley Chisholm, John Lewis, Maya Angelou and Mary Ellen Pleasant.

Following the lead of trailblazers throughout American history, today’s Black history-makers are shaping not only today but tomorrow. From helping to develop a Covid-19 vaccine, to breaking barriers in the White House and in the C-suite, below are 23 Black leaders who are shattering glass ceilings in their wide-ranging roles.

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)

Ten Years of Hope and Blood

Robert Solé in The Markaz Review:

It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia.

It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia.

Five days later, as protests erupted in Jordan, Yemen and Lebanon, and firebombings were reported in Algeria, Egypt and Mauritania, an Arab League summit was convened in Sharm el-Sheikh, South Sinai. For once, its secretary general, Amr Moussa abandons the language of wood. “Arab citizens,” he declares, “are in a state of unprecedented anger and frustration.”

More here.

Why “Trusting the Science” Is Complicated

Suman Seth in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

It is possible that John Pringle’s neighbors viewed him with some distaste. Formerly physician-general to the British forces in the Low Countries, in 1749 Pringle had settled down in a rather swanky part of London, where he began investigating the processes behind putrefaction. He would place pieces of beef in a lamp furnace, sometimes combining them with another substance — and then wait for putrefaction to commence, or not. Falsifying an earlier hypothesis, Pringle showed that not only acids but alkalis, like baker’s ammonia, could retard the progress of decay. Even more impressively, some substances, like Peruvian bark (source of the malarial prophylactic, quinine) could outright reverse putrefaction, rendering tainted meat seemingly edible again.

It is possible that John Pringle’s neighbors viewed him with some distaste. Formerly physician-general to the British forces in the Low Countries, in 1749 Pringle had settled down in a rather swanky part of London, where he began investigating the processes behind putrefaction. He would place pieces of beef in a lamp furnace, sometimes combining them with another substance — and then wait for putrefaction to commence, or not. Falsifying an earlier hypothesis, Pringle showed that not only acids but alkalis, like baker’s ammonia, could retard the progress of decay. Even more impressively, some substances, like Peruvian bark (source of the malarial prophylactic, quinine) could outright reverse putrefaction, rendering tainted meat seemingly edible again.

In 1752, Pringle used these results to make medical recommendations in a book entitled Diseases of the Army. Rot within the body, he asserted, accounted for a great many diseases afflicting soldiers in particular. It followed that substances that could slow down or reverse putrefaction could also — when swallowed — combat these diseases.

More here.

Yanis Varoufakis: Capitalism has become ‘techno-feudalism’

How Law Made Neoliberalism

Jedediah Britton-Purdy, Amy Kapczynski, and David Singh Grewal in the Boston Review:

We live in an era of intersecting crises—some new, some old but newly visible. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has already caused nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States alone, with many more deaths on the horizon in the coming months. Since its arrival in the United States, the virus has intersected with and magnified long-neglected problems—radical disparities in access to healthcare and the fulfillment of basic needs that disproportionately impact communities of color and working-class Americans, alongside a crisis of care for the young, elderly, and sick that stretches families and communities to the breaking point.

We live in an era of intersecting crises—some new, some old but newly visible. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has already caused nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States alone, with many more deaths on the horizon in the coming months. Since its arrival in the United States, the virus has intersected with and magnified long-neglected problems—radical disparities in access to healthcare and the fulfillment of basic needs that disproportionately impact communities of color and working-class Americans, alongside a crisis of care for the young, elderly, and sick that stretches families and communities to the breaking point.

These crises arise from the chronic failure of political institutions to respond democratically to public needs. They are rooted in decades of politics, policy, and law. For many Black, brown, rural, indigenous, and working-class Americans, this democratic failure is business as usual. But over the last four years, and especially since the storming of the Capitol, fear of democratic failure has become mainstream.

These crises are often analyzed in terms of the political economy of neoliberalism, an ideology of governance that came to predominate in the 1970s and ’80s. Neoliberalism is associated with a demand for deregulation, austerity, and an attempt to assimilate government to something more like a market—but it never was as simple as a demand for “free markets.” Rather, it was a demand to protect the market from democratic demands for redistribution.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Wild Dreams of a New Beginning

There’s a breathless hush on the freeway tonight

Beyond the ledges of concrete

restaurants fall into dreams

with candlelight couples

Lost Alexandria still burns

in a billion lightbulbs

Lives cross lives

idling at stoplights

Beyond the cloverleaf turnoffs

Souls eat souls in the general emptiness’

A piano concerto comes out a kitchen window

A yogi speaks at Ojai

It’s all taking pace in one mind’

On the lawn among the trees

lovers are listening

for the master to tell them they are one

with the universe

Eyes smell flowers and become them

There’s a deathless hush

on the freeway tonight

as a Pacific tidal wave a mile high

sweeps in

Los Angeles breathes its last gas

and sinks into the sea like the Titanic all lights lit

Nine minutes later Willa Cather’s Nebraska

sinks with it

Read more »

A Conversation with Bertrand Russell (1952)

Leonora Carrington’s ‘The Hearing Trumpet’

Jim Henderson at 3AM Magazine:

“People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable if they are not cats,” somebody says a few pages into Leonora Carrington’s 1974 novel The Hearing Trumpet. Most people would agree; if anything, the bad run of septuagenarians of late shows this age range is too narrow. The statement is characteristic of this chatoyant novel. Cats are everywhere in The Hearing Trumpet: their sheddings are collected to form a sleeveless cardigan; psychic powers are attributed to them; the earth freezes over and an earthquake thins out the human population, but the cats survive. Beneath its cattiness, the remark also offhandedly conflates species (the way “people” transmutes into “cats” at the end of the sentence) and recognizes the virtue of people usually excluded from civic life for being too young or too old. This broadening out of our ordinary categories of human life is at the heart of the novel.

“People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable if they are not cats,” somebody says a few pages into Leonora Carrington’s 1974 novel The Hearing Trumpet. Most people would agree; if anything, the bad run of septuagenarians of late shows this age range is too narrow. The statement is characteristic of this chatoyant novel. Cats are everywhere in The Hearing Trumpet: their sheddings are collected to form a sleeveless cardigan; psychic powers are attributed to them; the earth freezes over and an earthquake thins out the human population, but the cats survive. Beneath its cattiness, the remark also offhandedly conflates species (the way “people” transmutes into “cats” at the end of the sentence) and recognizes the virtue of people usually excluded from civic life for being too young or too old. This broadening out of our ordinary categories of human life is at the heart of the novel.

more here.

The Travel Journals Of Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Lawrence Ferlinghetti at The American Scholar:

To tell the truth, to tell the truth! Well-—this is the most depressing journey I have ever been on—Imagine having to spend one’s life condemned to passing from one motel to another, one hotel room to another, all of them alike, first class, the same spotless sheets, the same glasses in sanitary wax paper, the same little soap bars individually wrapped, Gideon Bible in the drawer, no one to speak with but hotel clerks, wives running motels in forlorn corners, bus drivers. Loneliness of millions living like this, between cocktails, between filling stations, between buses, trains, towns, restaurants, movies, highways leading over horizons to another Rest Stop. Sad the bundles in bus station waiting rooms, sad the frizzled women sitting next to them, the old couples on benches talking in old languages, the Mexicans with satchels they repack in men’s rooms. Sad hope of all their journeys to Nowhere and back in dark Eternity. … In the middle of the Journey of My Life, I came to myself in a dark wood.

more here.

Klara and the Sun – what it is to be human

Anne Enright in The Guardian:

Klara and the Sun asks readers to love a robot and, the funny thing is, we do. This is a novel not just about a machine but narrated by a machine, though the word is not used about her until late in the book when it is wielded by a stranger as an insult. People distrust and then start to like her: “Are you alright, Klara?” Apart from the occasional lapse into bullying or indifference, humans are solicitous of Klara’s feelings – if that is what they are. Klara is built to observe and understand humans, and these actions are so close to empathy they may amount to the same thing. “I believe I have many feelings,” she says. “The more I observe the more feelings become available to me.” Klara is an AF, or artificial friend, who is bought as a companion for 14-year-old Josie, a girl suffering from a mysterious, perhaps terminal illness. Klara is loyal and tactful, she is able to absorb difficulty and return care. Her role, as she describes it, is to prevent loneliness and to serve.

Klara and the Sun asks readers to love a robot and, the funny thing is, we do. This is a novel not just about a machine but narrated by a machine, though the word is not used about her until late in the book when it is wielded by a stranger as an insult. People distrust and then start to like her: “Are you alright, Klara?” Apart from the occasional lapse into bullying or indifference, humans are solicitous of Klara’s feelings – if that is what they are. Klara is built to observe and understand humans, and these actions are so close to empathy they may amount to the same thing. “I believe I have many feelings,” she says. “The more I observe the more feelings become available to me.” Klara is an AF, or artificial friend, who is bought as a companion for 14-year-old Josie, a girl suffering from a mysterious, perhaps terminal illness. Klara is loyal and tactful, she is able to absorb difficulty and return care. Her role, as she describes it, is to prevent loneliness and to serve.

…There is something so steady and beautiful about the way Klara is always approaching connection, like a Zeno’s arrow of the heart. People will absolutely love this book, in part because it enacts the way we learn how to love. Klara and the Sun is wise like a child who decides, just for a little while, to love their doll. “What can children know about genuine love?” Klara asks. The answer, of course, is everything.

More here.

How Nations Heal

Colleen Murphy in Boston Review:

Transitional justice is both a legal and philosophical theory and a global practice that aims to redress wrongdoing, past and present, in order to vindicate victims, hold perpetrators to account, and transform relationships—among citizens as well as between citizens and public officials. Though it is not as well known in the United States as other paradigms of justice, the framework has been adopted in dozens of countries emerging from periods of war, genocide, dictatorship, and repression, from South Africa to Colombia. As a global practice, the framework began with the recognition that simply moving on hadn’t worked.

Transitional justice is both a legal and philosophical theory and a global practice that aims to redress wrongdoing, past and present, in order to vindicate victims, hold perpetrators to account, and transform relationships—among citizens as well as between citizens and public officials. Though it is not as well known in the United States as other paradigms of justice, the framework has been adopted in dozens of countries emerging from periods of war, genocide, dictatorship, and repression, from South Africa to Colombia. As a global practice, the framework began with the recognition that simply moving on hadn’t worked.

From the vantage of transitional justice, healing of communities can only occur if we first understand what is damaged, and damage can only be repaired if it is truly acknowledged and addressed. And to help to prevent recurrence of atrocity, we need to draw a line between what was accepted in the past and what will be acceptable in the future. The particular measures used to achieve these aims have ranged from truth commissions and criminal investigations and prosecutions to reparations, lustration (vetting government officials for ties to repressive regimes or activity), and other legal and institutional changes.

To illustrate how transitional justice differs from other frameworks of justice, consider restorative justice, which prioritizes the repair of ruptured relationships among victim, offender, and community caused by wrongdoing. Repair occurs via a model of amends—characteristically via apology and reparations—followed by forgiveness.

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)