Andy Kroll in Rolling Stone:

Sander van der Linden was working in his office at the University of Cambridge a few years ago when he received a strange phone call. A professor of social psychology and director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Laboratory, van der Linden is one of the world’s leading researchers on how to combat the scourge of disinformation and misinformation. He receives requests all the time about his work from government agencies, media organizations, and civil-society groups. But the person who called that day was not a bureaucrat or a diplomat. It was a representative from L’Oréal, the multi-billion-dollar global beauty product company. L’Oréal had what it called a “scientific disinformation” problem related to some of its products. Could van der Linden help?

At the heart of van der Linden’s research is a theory: Our information crisis can and should be treated like a virus. Responding to fake stories or conspiracy theories after the fact is woefully insufficient, just as post-infection treatments don’t compare to vaccines. Indeed, a growing body of social science suggests that fact-checks and debunkings do little to correct falsehoods after people have seen a piece of misinformation (the unintentional spread of misleading or false stories) or disinformation (the intentional spread of such a story with a purpose in mind). Van der Linden believes we can protect people against bad information through something akin to inoculation. A truth vaccine. He calls this tactic “prebunking.”

More here.

Scientists have come up with a computer program that can master a variety of 1980s exploration games, paving the way for more self-sufficient robots.

Scientists have come up with a computer program that can master a variety of 1980s exploration games, paving the way for more self-sufficient robots. Last spring,

Last spring,  Since its consolidation at the end of the eighteenth century, the realist novel has been the premier vehicle for the depiction of contemporary life. For over two hundred years, a relatively fixed set of representational techniques – point-of-view, voice, description, dialogue, plot – has managed to adapt to the radical transformations of modernity: the nuclearization of the family, the entry of women into public life, the liberalization of sexual mores, industrialization and deindustrialization, urbanization and suburbanization, secularization, the lifeworlds of dominated classes and colonized nations, war on a planetary scale, and new conceptions of cognition and identity formation, to name just a few. By doubling down on its core strength – the linguistic representation of inner experience – the novel even managed to fend off challenges from rival media, like film and television. But over the last decade or so it has become clear that changes in the texture of the contemporary itself, due primarily to the diffusion of digital networked media, have begun to strain the capacity of the novel – as an institution, as a medium, as a form – to fulfil its traditional remit.

Since its consolidation at the end of the eighteenth century, the realist novel has been the premier vehicle for the depiction of contemporary life. For over two hundred years, a relatively fixed set of representational techniques – point-of-view, voice, description, dialogue, plot – has managed to adapt to the radical transformations of modernity: the nuclearization of the family, the entry of women into public life, the liberalization of sexual mores, industrialization and deindustrialization, urbanization and suburbanization, secularization, the lifeworlds of dominated classes and colonized nations, war on a planetary scale, and new conceptions of cognition and identity formation, to name just a few. By doubling down on its core strength – the linguistic representation of inner experience – the novel even managed to fend off challenges from rival media, like film and television. But over the last decade or so it has become clear that changes in the texture of the contemporary itself, due primarily to the diffusion of digital networked media, have begun to strain the capacity of the novel – as an institution, as a medium, as a form – to fulfil its traditional remit. During a rare excursion to a clothes shop I took last month, an older woman walked in, looked around at the other shoppers and exclaimed, “humans!” It was an unusual moment of bonding with strangers. Mostly I just hold my breath as people squeeze past me at the supermarket. In this year of staying two metres away from practically everyone, we’ve all become used to treating other people as potentially toxic. Now that vaccinations are under way, we’re allowed to hope that we will one day emerge from hibernation. What will socialising be like on the other side? And how will we cope with being together again?

During a rare excursion to a clothes shop I took last month, an older woman walked in, looked around at the other shoppers and exclaimed, “humans!” It was an unusual moment of bonding with strangers. Mostly I just hold my breath as people squeeze past me at the supermarket. In this year of staying two metres away from practically everyone, we’ve all become used to treating other people as potentially toxic. Now that vaccinations are under way, we’re allowed to hope that we will one day emerge from hibernation. What will socialising be like on the other side? And how will we cope with being together again? Black History Month has been celebrated in the United States for close to 100 years. But what is it, exactly, and how did it begin?

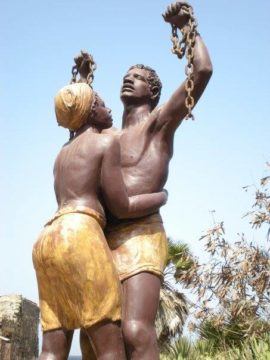

Black History Month has been celebrated in the United States for close to 100 years. But what is it, exactly, and how did it begin? Joshua Cohen in Boston Review:

Joshua Cohen in Boston Review: Jamie McCallum in Aeon:

Jamie McCallum in Aeon: Elizabeth Anderson in The Nation:

Elizabeth Anderson in The Nation: Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire in The Atlantic:

Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire in The Atlantic: The Believer is the highly anticipated second book from Sarah Krasnostein, author of multi-award-winning

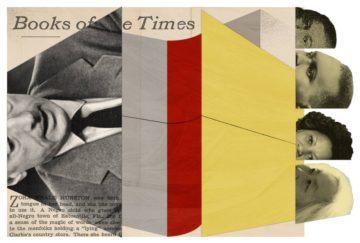

The Believer is the highly anticipated second book from Sarah Krasnostein, author of multi-award-winning  To wander through 125 years of book reviews is to endure assault by adjective. All the fatuous books, the frequently brilliant, the disappointing, the essential. The adjectives one only ever encounters in a review (indelible, risible), the archaic descriptors (sumptuous). So many masterpieces, so many duds — now enjoying quiet anonymity.

To wander through 125 years of book reviews is to endure assault by adjective. All the fatuous books, the frequently brilliant, the disappointing, the essential. The adjectives one only ever encounters in a review (indelible, risible), the archaic descriptors (sumptuous). So many masterpieces, so many duds — now enjoying quiet anonymity. I HAVE NEVER FELT WELCOME

I HAVE NEVER FELT WELCOME  In an effort to honor this expansive and growing history, Black History Month was established by way of a weekly celebration in February known as “Negro History Week” by historian Carter G. Woodson. But just as Black history is more than a month, so too are the numerous events and figures that are often overlooked during it. What follows is a list of some of those “lesser known” moments and facts in Black history.

In an effort to honor this expansive and growing history, Black History Month was established by way of a weekly celebration in February known as “Negro History Week” by historian Carter G. Woodson. But just as Black history is more than a month, so too are the numerous events and figures that are often overlooked during it. What follows is a list of some of those “lesser known” moments and facts in Black history.