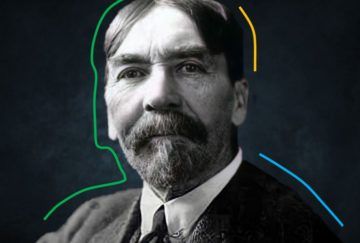

Ryan P. Hanley in the National Review:

Adam Smith is today known as the founding father of economics. But by profession he was a university professor, holding a chair in moral philosophy. It was in this capacity that in 1759 he published the first of his two books. Neither can be fully appreciated without the other — and both deserve our careful attention now, perhaps more than ever.

Adam Smith is today known as the founding father of economics. But by profession he was a university professor, holding a chair in moral philosophy. It was in this capacity that in 1759 he published the first of his two books. Neither can be fully appreciated without the other — and both deserve our careful attention now, perhaps more than ever.

Smith’s first book was The Theory of Moral Sentiments. An instant hit, it early on caught the attention of such prominent admirers as Edmund Burke, David Hume, and John Adams. The aim of the book is at once descriptive and prescriptive. It is descriptive insofar as it provides an account of the moral institutions that enable a free society to function. And it is prescriptive insofar as it seeks to cultivate the qualities of character that allow free individuals to lead flourishing lives and free societies to prosper and persist.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments covers a great deal of ground, tackling topics ranging from justice and judgment to conscience and love. But its most original and important contributions arguably come on three specific fronts: its theory of sympathy, its concept of the impartial spectator, and its vision of virtue.

More here.

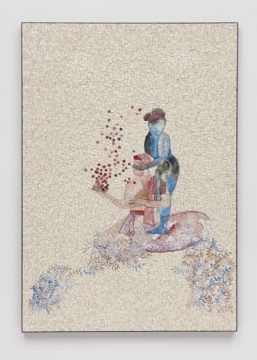

Shahzia Sikander’s first New York solo exhibition in more than a decade showcases an astonishing range of work: paintings, mosaics, animations, and her inaugural foray into freestanding sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies, a stunning monument to desire that depicts both a Greco-Roman goddess and an Indian devata. Sikander is an artist whose talents and ambitions threaten to outstrip the materials available to her; the works featured here confront the climate crisis, religion, migration, war, memory, and much more. But despite the daunting abundance of ideas and mediums, careful attention reveals that the show itself is a sort of mosaic, the pieces all slotting into place to form a portrait of the artist over the past few years of her practice. The works on paper inform the animations; the animations inform the individual mosaics (in part, Sikander credits her experiments with the latter form to “the dynamism of the pixel that emerged in my mind as a parallel to the unit of a mosaic”).

Shahzia Sikander’s first New York solo exhibition in more than a decade showcases an astonishing range of work: paintings, mosaics, animations, and her inaugural foray into freestanding sculpture, Promiscuous Intimacies, a stunning monument to desire that depicts both a Greco-Roman goddess and an Indian devata. Sikander is an artist whose talents and ambitions threaten to outstrip the materials available to her; the works featured here confront the climate crisis, religion, migration, war, memory, and much more. But despite the daunting abundance of ideas and mediums, careful attention reveals that the show itself is a sort of mosaic, the pieces all slotting into place to form a portrait of the artist over the past few years of her practice. The works on paper inform the animations; the animations inform the individual mosaics (in part, Sikander credits her experiments with the latter form to “the dynamism of the pixel that emerged in my mind as a parallel to the unit of a mosaic”). Ageing affects the body in myriad ways — among them, adding, removing or altering chemical groups such as methyls on DNA. These ‘epigenetic’ changes accumulate as a person ages, and some researchers have proposed tracking the changes as a way of calibrating a molecular clock to measure biological age, an assessment that takes into account biological wear-and-tear and can differ from chronological age. That has raised the possibility that epigenetic changes contribute to the effects of ageing. “We set out with a question: if epigenetic changes are a driver of ageing, can you reset the epigenome?” says David Sinclair, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the Nature study. “Can you reverse the clock?”

Ageing affects the body in myriad ways — among them, adding, removing or altering chemical groups such as methyls on DNA. These ‘epigenetic’ changes accumulate as a person ages, and some researchers have proposed tracking the changes as a way of calibrating a molecular clock to measure biological age, an assessment that takes into account biological wear-and-tear and can differ from chronological age. That has raised the possibility that epigenetic changes contribute to the effects of ageing. “We set out with a question: if epigenetic changes are a driver of ageing, can you reset the epigenome?” says David Sinclair, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the Nature study. “Can you reverse the clock?”

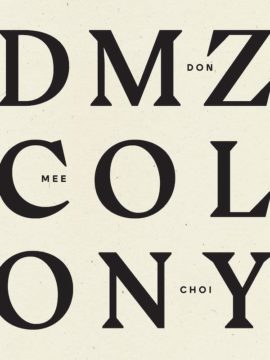

When asked in an interview with Words Without Borders to give an example of an untranslatable word in Korean, Choi answers that duplicatives, “adverbs or adjectives that are repeated to form a pair,” poses a challenge. “Such doubling is the norm in Korean, and it accentuates the sounds, which can also have the phonetic or mimetic effects of onomatopoeia.” Her solution is often to use a similar tactic in English, such as “swarmsswarms” or “waddlewaddling.” In “Orphan Kim Seong-rye,” she uses the doubling technique twice: “Oblong oblong” and “circled and circled.” While the latter sounds natural in English, the former is more difficult to digest. It demands the reader’s attention, and the reader lingers over the phrase — oblong oblong, oblong oblong… — until all that remains is the sound.

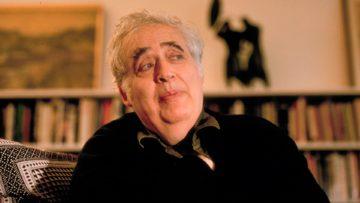

When asked in an interview with Words Without Borders to give an example of an untranslatable word in Korean, Choi answers that duplicatives, “adverbs or adjectives that are repeated to form a pair,” poses a challenge. “Such doubling is the norm in Korean, and it accentuates the sounds, which can also have the phonetic or mimetic effects of onomatopoeia.” Her solution is often to use a similar tactic in English, such as “swarmsswarms” or “waddlewaddling.” In “Orphan Kim Seong-rye,” she uses the doubling technique twice: “Oblong oblong” and “circled and circled.” While the latter sounds natural in English, the former is more difficult to digest. It demands the reader’s attention, and the reader lingers over the phrase — oblong oblong, oblong oblong… — until all that remains is the sound. Flip through Don DeLillo’s massive corpus, and you may notice that the word “silence” crops up, again and again, at crucial moments. It’s the first word he spoke to the public when, in 1982, he gave his first, reluctant interview. Why, asked the critic Tom LeClair, did DeLillo shun the public eye? “Silence, exile, cunning, and so on,” the author responded, quoting Stephen Dedalus, tongue in cheek. It’s a word that then wended through his work, uttered by his secretive, mysterious men—“Silence,” says Underworld’s Nick Shay, “is the condition you accept as a judgment on your crimes.” It’s a word that, finally, became the target of his most serious critic, James Wood. Far from quiet, Wood complained in a 2000 essay, DeLillo’s books simply could not shut up. Underworld in particular—his vast 1997 Cold War epic—seemed gripped by the delusion that it “might never have to end.” “There are many enemies, seen and unseen, in Underworld,” wrote Wood, “but silence is not one of them.”

Flip through Don DeLillo’s massive corpus, and you may notice that the word “silence” crops up, again and again, at crucial moments. It’s the first word he spoke to the public when, in 1982, he gave his first, reluctant interview. Why, asked the critic Tom LeClair, did DeLillo shun the public eye? “Silence, exile, cunning, and so on,” the author responded, quoting Stephen Dedalus, tongue in cheek. It’s a word that then wended through his work, uttered by his secretive, mysterious men—“Silence,” says Underworld’s Nick Shay, “is the condition you accept as a judgment on your crimes.” It’s a word that, finally, became the target of his most serious critic, James Wood. Far from quiet, Wood complained in a 2000 essay, DeLillo’s books simply could not shut up. Underworld in particular—his vast 1997 Cold War epic—seemed gripped by the delusion that it “might never have to end.” “There are many enemies, seen and unseen, in Underworld,” wrote Wood, “but silence is not one of them.” On May 19,

On May 19,  In 1893 financial panic triggered a four-year depression in the United States, then the most severe in the nation’s history. Bank runs, shuttered factories, and plummeting wheat prices put millions out of work. In Chicago alone, as many as 180,000 workers were jobless by the end of the year.

In 1893 financial panic triggered a four-year depression in the United States, then the most severe in the nation’s history. Bank runs, shuttered factories, and plummeting wheat prices put millions out of work. In Chicago alone, as many as 180,000 workers were jobless by the end of the year. Seamus Perry and Mark Ford discuss the life and work of Louis MacNeice, the Irish poet of psychic divisions and authoritative fretfulness.

Seamus Perry and Mark Ford discuss the life and work of Louis MacNeice, the Irish poet of psychic divisions and authoritative fretfulness. A certain scene between Marguerite Duras and Susan Sontag, told to me by someone who was friends with both and seated between them while Susan was visiting Paris, goes like this: Duras had just made a new film, and, in keeping with her character, she spoke at Susan in a monologic séance, going on and on about herself, her new film, and critical reactions to her new film. After speaking for most of the occasion they were together, Duras suddenly quieted and seemed to notice Sontag qua Sontag, and not just any old audience to her tirade. “Susan! My goodness. I have only talked and talked, and I haven’t let you speak a word! Please, tell me everything.” At this, Susan—or can we even say “poor Susan”—beamed like a child who was finally getting the attention she’d sought. Duras continued, “I want every detail! What did you think of my new film?”

A certain scene between Marguerite Duras and Susan Sontag, told to me by someone who was friends with both and seated between them while Susan was visiting Paris, goes like this: Duras had just made a new film, and, in keeping with her character, she spoke at Susan in a monologic séance, going on and on about herself, her new film, and critical reactions to her new film. After speaking for most of the occasion they were together, Duras suddenly quieted and seemed to notice Sontag qua Sontag, and not just any old audience to her tirade. “Susan! My goodness. I have only talked and talked, and I haven’t let you speak a word! Please, tell me everything.” At this, Susan—or can we even say “poor Susan”—beamed like a child who was finally getting the attention she’d sought. Duras continued, “I want every detail! What did you think of my new film?” Just before Thanksgiving in November 2005, paediatrician Ruchi Gupta gathered some parents of children with food allergies in an office building. She aimed to collect data on their knowledge and beliefs about allergies, but the conversation quickly turned emotional. One parent described how her family wouldn’t be joining the big Thanksgiving gathering because of her son’s allergy. “She started crying and she was very emotional about it, and said they were just going to do Thanksgiving on their own,” recalls Gupta, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern and Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. “The whole focus group became pretty intense and tissue boxes came out.” The meeting was planned to last an hour, but people stayed well into a third. Other parents opened up about their distress. “They started talking about their experiences in every realm of life: people who didn’t believe them, even in their own families. A lot of times the grandparents would say, ‘Oh, you’re just over-protective. We didn’t have this in my day’.”

Just before Thanksgiving in November 2005, paediatrician Ruchi Gupta gathered some parents of children with food allergies in an office building. She aimed to collect data on their knowledge and beliefs about allergies, but the conversation quickly turned emotional. One parent described how her family wouldn’t be joining the big Thanksgiving gathering because of her son’s allergy. “She started crying and she was very emotional about it, and said they were just going to do Thanksgiving on their own,” recalls Gupta, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern and Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. “The whole focus group became pretty intense and tissue boxes came out.” The meeting was planned to last an hour, but people stayed well into a third. Other parents opened up about their distress. “They started talking about their experiences in every realm of life: people who didn’t believe them, even in their own families. A lot of times the grandparents would say, ‘Oh, you’re just over-protective. We didn’t have this in my day’.” On a scale of 0 to 10, I’d say my happiness ranks at about a 6. I’d guess my wife’s is at least a 9. I try not to envy her natural Spanish

On a scale of 0 to 10, I’d say my happiness ranks at about a 6. I’d guess my wife’s is at least a 9. I try not to envy her natural Spanish  Tennyson’s poem ‘Mariana’ has gone everywhere in the world since 1830. A professional scholar in Uruguay, Papua New Guinea or New Haven, Connecticut, reading the lines ‘Weeded and worn the ancient thatch/Upon the lonely moated grange’ might want to ask a few questions. Do English houses ever have moats? (Yes — Ightham Mote and Madresfield Court are famous examples.) Can we find houses with a humble thatch and also a moat? (A harder question – Tennyson’s poem set a vogue in landscape design as well as poetry.) Or, taking a different tack, where does the use of the word ‘moat’ as a verb come from? (Easy — ‘moated grange’ is from the poem’s subject, Measure for Measure.) What sort of word was it by 1830? (Harder — it comes up in translations with a taste for the archaic, and technical descriptions of architecture. Is it picturesque in a way that Shakespeare’s use isn’t?) These are interesting questions that might lead to some kind of enlightenment.

Tennyson’s poem ‘Mariana’ has gone everywhere in the world since 1830. A professional scholar in Uruguay, Papua New Guinea or New Haven, Connecticut, reading the lines ‘Weeded and worn the ancient thatch/Upon the lonely moated grange’ might want to ask a few questions. Do English houses ever have moats? (Yes — Ightham Mote and Madresfield Court are famous examples.) Can we find houses with a humble thatch and also a moat? (A harder question – Tennyson’s poem set a vogue in landscape design as well as poetry.) Or, taking a different tack, where does the use of the word ‘moat’ as a verb come from? (Easy — ‘moated grange’ is from the poem’s subject, Measure for Measure.) What sort of word was it by 1830? (Harder — it comes up in translations with a taste for the archaic, and technical descriptions of architecture. Is it picturesque in a way that Shakespeare’s use isn’t?) These are interesting questions that might lead to some kind of enlightenment.