Simon Torracinta in the Boston Review:

In 1893 financial panic triggered a four-year depression in the United States, then the most severe in the nation’s history. Bank runs, shuttered factories, and plummeting wheat prices put millions out of work. In Chicago alone, as many as 180,000 workers were jobless by the end of the year.

In 1893 financial panic triggered a four-year depression in the United States, then the most severe in the nation’s history. Bank runs, shuttered factories, and plummeting wheat prices put millions out of work. In Chicago alone, as many as 180,000 workers were jobless by the end of the year.

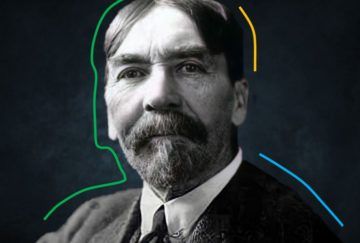

An attempt by the Pullman Palace Car Company in the city’s South Side to impose a 30 percent wage cut on its workforce in the spring of 1894 led to a walkout by the newly formed American Railway Union, led by Eugene Debs (not yet famous as the socialist firebrand who would later win 6 percent of the vote in the 1912 presidential election). It quickly escalated into full-scale boycott of luxury Pullman cars by hundreds of thousands of railroad workers across the country—the infamous Pullman strike, which took place between May and July. With the railways paralyzed, President Grover Cleveland sent federal troops to Chicago, and pitched battles—at times lethal—erupted in working-class neighborhoods. “This is no longer a strike,” the Chicago Tribune thundered: “This is a revolution.” That same spring, hundreds of desperate, unemployed workers, calling themselves the Army of the Commonwealth of Christ, marched from Ohio to the White House, demanding the federal government offer relief in the form of an ambitious public works program to be funded by the unprecedented issuance of fiat money. Another 700 workers from the northwest forcefully commandeered a train to make the trip to D.C., fending off marshals until federal troops intercepted them in Montana.

This was the atmosphere surrounding the campus of the University of Chicago, then only a few years old, which had just hired a young Norwegian-American economist named Thorstein Veblen two years earlier.

More here.