Taimur Khan in Foreign Policy:

A decade before the arrival of New York Times correspondent Declan Walsh’s The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches from a Precarious State—which was released in the United States on Nov. 23—another major book of long-form reportage about the country’s chaotic post-9/11 years was published: Nicholas Schmidle’s To Live or to Perish Forever. The two books open with anecdotes of the authors being suddenly ordered to pack their bags and expelled from the country after reporting stories that crossed a red line for Pakistan’s security services—Schmidle for reporting on the Pakistani mutation of the Taliban and Walsh for his coverage of the insurgency in the vast, rural Balochistan province. Walsh’s book comes more than seven years after he was kicked out of Pakistan in May 2013.

A decade before the arrival of New York Times correspondent Declan Walsh’s The Nine Lives of Pakistan: Dispatches from a Precarious State—which was released in the United States on Nov. 23—another major book of long-form reportage about the country’s chaotic post-9/11 years was published: Nicholas Schmidle’s To Live or to Perish Forever. The two books open with anecdotes of the authors being suddenly ordered to pack their bags and expelled from the country after reporting stories that crossed a red line for Pakistan’s security services—Schmidle for reporting on the Pakistani mutation of the Taliban and Walsh for his coverage of the insurgency in the vast, rural Balochistan province. Walsh’s book comes more than seven years after he was kicked out of Pakistan in May 2013.

In news reporting, most of the work must frustratingly remain in a journalist’s notebook. Walsh draws on these notebooks to write his book, finally able to give previous reporting trips the full literary treatment that they deserve. But it raises the question of whether reporting from Pakistan, some of it nearly 20 years old, gives readers new insights into a uniquely complex society. Walsh himself claims he will take the reader with him, retracing his steps, on a journey “deep into the psyche of the country.”

Walsh’s book is better than Schmidle’s, but the nearly identical opening scenes are a metaphor for a larger problem with writing about Pakistan, an ethnically diverse nation of more than 200 million people that is in constant flux. In the decade between the publication of these two major books of reportage that purport to explain Pakistan, the country itself has grown and evolved rapidly. The Pakistan discourse has still not caught up.

More here.

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

The best thing about David Fincher’s new film, “Mank,” is that it isn’t about what one expects it to be about. More specifically, the movie (which is streaming on Netflix) is not about the assertion, made most strenuously by Pauline Kael in her controversial New Yorker piece “

The best thing about David Fincher’s new film, “Mank,” is that it isn’t about what one expects it to be about. More specifically, the movie (which is streaming on Netflix) is not about the assertion, made most strenuously by Pauline Kael in her controversial New Yorker piece “ IN HER MEMOIR

IN HER MEMOIR Over at his

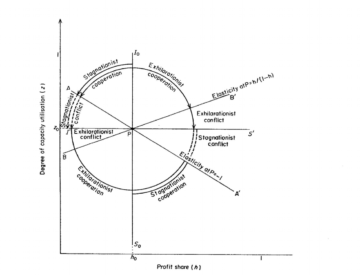

Over at his  Maya Adereth interviews Amit Bhaduri in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth interviews Amit Bhaduri in Phenomenal World: I

I There’s plenty wrong with rights, Nigel Biggar tells us, as some very powerful thinkers have been saying since the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’ first entered the lexicon of mass democratic politics during the French Revolution. This sceptical tradition has been particularly strong in Britain, a country that likes to think it invented rights at Runnymede. It runs from Edmund Burke, through Jeremy Bentham (who called natural rights ‘nonsense on stilts’) right up to contemporary figures like Jonathan Sumption, a former justice of the UK Supreme Court, and the philosopher Onora O’Neill.

There’s plenty wrong with rights, Nigel Biggar tells us, as some very powerful thinkers have been saying since the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’ first entered the lexicon of mass democratic politics during the French Revolution. This sceptical tradition has been particularly strong in Britain, a country that likes to think it invented rights at Runnymede. It runs from Edmund Burke, through Jeremy Bentham (who called natural rights ‘nonsense on stilts’) right up to contemporary figures like Jonathan Sumption, a former justice of the UK Supreme Court, and the philosopher Onora O’Neill. The

The As a child, Suzanne Simard often roamed Canada’s old-growth forests with her siblings, building forts from fallen branches, foraging mushrooms and huckleberries and occasionally eating handfuls of dirt (she liked the taste). Her grandfather and uncles, meanwhile, worked nearby as horse loggers, using low-impact methods to selectively harvest cedar, Douglas fir and white pine. They took so few trees that Simard never noticed much of a difference. The forest seemed ageless and infinite, pillared with conifers, jeweled with raindrops and brimming with ferns and fairy bells. She experienced it as “nature in the raw” — a mythic realm, perfect as it was. When she began attending the University of British Columbia, she was elated to discover forestry: an entire field of science devoted to her beloved domain. It seemed like the natural choice.

As a child, Suzanne Simard often roamed Canada’s old-growth forests with her siblings, building forts from fallen branches, foraging mushrooms and huckleberries and occasionally eating handfuls of dirt (she liked the taste). Her grandfather and uncles, meanwhile, worked nearby as horse loggers, using low-impact methods to selectively harvest cedar, Douglas fir and white pine. They took so few trees that Simard never noticed much of a difference. The forest seemed ageless and infinite, pillared with conifers, jeweled with raindrops and brimming with ferns and fairy bells. She experienced it as “nature in the raw” — a mythic realm, perfect as it was. When she began attending the University of British Columbia, she was elated to discover forestry: an entire field of science devoted to her beloved domain. It seemed like the natural choice. Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in

Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in  For the first time, a quantum computer made from photons—particles of light—has outperformed even the fastest classical supercomputers.

For the first time, a quantum computer made from photons—particles of light—has outperformed even the fastest classical supercomputers.