Andrew Jewett in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic, told humanities majors at a Brandeis University graduation ceremony that they represented “the resistance” in a society dominated by “the twin imperialisms of science and technology.” Wieseltier sounded all the familiar themes — the enslavement of human beings to machines, the tyranny of numbers, the depredations of “technologism,” the unchallenged dominance of “utility, speed, efficiency, and convenience” in modern culture. The antidote, he claimed, was the humanities.

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic, told humanities majors at a Brandeis University graduation ceremony that they represented “the resistance” in a society dominated by “the twin imperialisms of science and technology.” Wieseltier sounded all the familiar themes — the enslavement of human beings to machines, the tyranny of numbers, the depredations of “technologism,” the unchallenged dominance of “utility, speed, efficiency, and convenience” in modern culture. The antidote, he claimed, was the humanities.

The evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker fired back. Petulant humanists, he charged, welcomed science when it cured disease but not when it impinged on their professional fiefdom. The march of science and the Enlightenment had vastly improved the human condition. Only science, Pinker insisted, could address “the deepest questions about who we are, where we came from, and how we define the meaning and purpose of our lives.” Humanities scholars would remain irrelevant until they embraced the scientifically informed humanitarianism that constituted the “de facto morality” of the modern world. The ensuing controversy stretched through that summer and fall.

Today a global pandemic grips the world. Societies face immediate, practical, life-or-death questions about how to incorporate science and expertise into their collective decisions. And yet the old refrains can still be heard. In Commentary, the conservative commentator Sohrab Ahmari argued that “the ideology of scientism” has plunged the world into “a half-millennial funk.” In the face of a deadly virus, Ahmari wrote, moderns lack any sense of why “life is worth living and passing on”; they cannot even assert that “being is preferable to nonbeing.” Pinker chimed in as well, arguing that political decisions favoring economic well-being over bodily health reflected the “malignant delusion” of evangelicals’ “belief in an afterlife,” which “devalues actual lives.”

And so the tired, decades-old pattern continues.

More here.

Because there are many things to say about Susan Taubes’s remarkable 1969 novel “Divorcing,” and many of those things concern the grim side of both real life and life in the book, I’d like to start by saying that it’s funny. It’s not a comic novel, by any stretch, but neglecting to mention its humor would shortchange it and deform one’s initial idea of it.

Because there are many things to say about Susan Taubes’s remarkable 1969 novel “Divorcing,” and many of those things concern the grim side of both real life and life in the book, I’d like to start by saying that it’s funny. It’s not a comic novel, by any stretch, but neglecting to mention its humor would shortchange it and deform one’s initial idea of it.

T

T

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,  When I was a graduate student in international relations in the early 2000s, my teachers would frequently invoke the famous, though possibly apocryphal, response of the late Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai to the question of whether the French Revolution had been a success: “It’s too soon to tell.” Contemplating the same arc of history that forms the subtext of Zhou’s reply, we might see the United States today bending gingerly away from populist indignation and toward a potentially gentler interval of governance. Though the nation’s attention is rightly focused on domestic matters, above all on contending with a devasting pandemic, changes at the helm mean that it is open season for grand visioning from the heights, particularly as concerns America’s place in the world. Are we dispensable? Indispensable? Exceptional? Banal? Imperialist? Heroic? Or simply unsound?

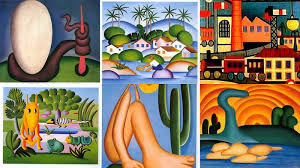

When I was a graduate student in international relations in the early 2000s, my teachers would frequently invoke the famous, though possibly apocryphal, response of the late Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai to the question of whether the French Revolution had been a success: “It’s too soon to tell.” Contemplating the same arc of history that forms the subtext of Zhou’s reply, we might see the United States today bending gingerly away from populist indignation and toward a potentially gentler interval of governance. Though the nation’s attention is rightly focused on domestic matters, above all on contending with a devasting pandemic, changes at the helm mean that it is open season for grand visioning from the heights, particularly as concerns America’s place in the world. Are we dispensable? Indispensable? Exceptional? Banal? Imperialist? Heroic? Or simply unsound? The Confederate immigrants didn’t impose their way of life in São Paulo’s rural interior. On neighboring plantations, enslaved women were raising the white artists who would become the country’s major modernists. Brazil’s most famous modernist painter, Tarsila do Amaral, muse of Antropofagia, grew up on her family’s coffee plantation, a half hour’s drive from the American colony. Antropofagia was a movement of “cultural cannibalism” based on a caricature of the Tupi indigenous people as cannibals; elite white Brazilians would “cannibalize” French styles in the production of Brazilian subject matter: Black people. A year before her death, do Amaral explained that the subject for her first anthropophagic painting, A Negra (1923), was a “female slave” she remembered from her youth, and described in vivid detail I won’t repeat how the woman had stretched her breasts so that she might breastfeed while working. Chattel slavery legally ended in Brazil on May 13, 1888, when do Amaral was one year old, so her explanation was technically anachronistic. Either emancipation passed without notice, or her family’s plantation hummed along under a new economic arrangement so closely resembling slavery that she still referred to wage workers as “slaves.”

The Confederate immigrants didn’t impose their way of life in São Paulo’s rural interior. On neighboring plantations, enslaved women were raising the white artists who would become the country’s major modernists. Brazil’s most famous modernist painter, Tarsila do Amaral, muse of Antropofagia, grew up on her family’s coffee plantation, a half hour’s drive from the American colony. Antropofagia was a movement of “cultural cannibalism” based on a caricature of the Tupi indigenous people as cannibals; elite white Brazilians would “cannibalize” French styles in the production of Brazilian subject matter: Black people. A year before her death, do Amaral explained that the subject for her first anthropophagic painting, A Negra (1923), was a “female slave” she remembered from her youth, and described in vivid detail I won’t repeat how the woman had stretched her breasts so that she might breastfeed while working. Chattel slavery legally ended in Brazil on May 13, 1888, when do Amaral was one year old, so her explanation was technically anachronistic. Either emancipation passed without notice, or her family’s plantation hummed along under a new economic arrangement so closely resembling slavery that she still referred to wage workers as “slaves.” Samuel Johnson famously remarked, ‘It is commonly observed, that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know.’ Virginia Woolf politely added that Englishwomen also talk about the weather but thought there should be strict rules attached to all such discussions. A hostess or a novelist might talk about the weather to settle a guest or a reader, but they should move swiftly on to more interesting themes. A novel that considers nothing but the weather was most probably written by Arnold Bennett (I paraphrase). Mark Twain took this further, promising in the opening of The American Claimant that ‘no weather will be found in this book’ as ‘it is plain that persistent intrusions of weather are bad for both reader and author’.

Samuel Johnson famously remarked, ‘It is commonly observed, that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know.’ Virginia Woolf politely added that Englishwomen also talk about the weather but thought there should be strict rules attached to all such discussions. A hostess or a novelist might talk about the weather to settle a guest or a reader, but they should move swiftly on to more interesting themes. A novel that considers nothing but the weather was most probably written by Arnold Bennett (I paraphrase). Mark Twain took this further, promising in the opening of The American Claimant that ‘no weather will be found in this book’ as ‘it is plain that persistent intrusions of weather are bad for both reader and author’. Given that

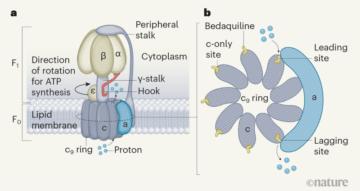

Given that  The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of an imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy. On bestowing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that this technique has “moved biochemistry into a new era”.

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of an imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy. On bestowing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that this technique has “moved biochemistry into a new era”.

“Surely, after 62 years, we should have an exact formulation of some serious part of quantum mechanics?” wrote the eminent Northern Irish physicist John Bell in the opening salvo of his Physics World article, “

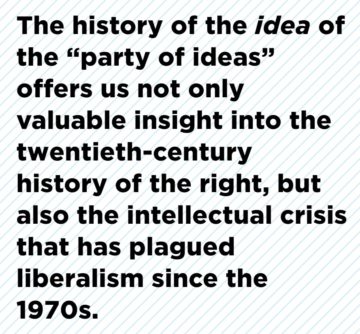

“Surely, after 62 years, we should have an exact formulation of some serious part of quantum mechanics?” wrote the eminent Northern Irish physicist John Bell in the opening salvo of his Physics World article, “ For many conservative pundits, the election of Donald Trump marked the moment when the Republican Party abandoned its longstanding claim to being the “party of ideas.” For example, in June 2017 longtime Republican policy advisor Bruce Bartlett wrote, “Trump is what happens when a political party abandons ideas.” For Bartlett, though, it had been a long decline, dating back decades. Likewise, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell argued that “somehow the Party of Ideas stopped coming up with them circa, oh, 1987.”

For many conservative pundits, the election of Donald Trump marked the moment when the Republican Party abandoned its longstanding claim to being the “party of ideas.” For example, in June 2017 longtime Republican policy advisor Bruce Bartlett wrote, “Trump is what happens when a political party abandons ideas.” For Bartlett, though, it had been a long decline, dating back decades. Likewise, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell argued that “somehow the Party of Ideas stopped coming up with them circa, oh, 1987.” Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,  Could there possibly be an upside to the long, stressful periods of isolation that so many people have endured during the pandemic lockdown of 2020? When we emerge, will we see the world in a new way? Could there even be a silver lining to these months of quiet living and self-reflection?

Could there possibly be an upside to the long, stressful periods of isolation that so many people have endured during the pandemic lockdown of 2020? When we emerge, will we see the world in a new way? Could there even be a silver lining to these months of quiet living and self-reflection?