by Tim Sommers

Some good news, amongst all the bad this month. Our medieval Supreme Court took a break from being irredeemably awful to decide a case in the right way for the right reason. In Bostock v Clayton County, Georgia, Neil Gorsuch – yes, that Neil Gorsuch, the one nominated to the court by Donald Trump, who once ruled against a man in an unlawful termination case for leaving a truck by the side of the road rather than freezing to death in it – wrote the decision for himself, Chief Justice John Roberts and the four more liberal justices. The Court concluded that an employer violates the law – specifically, Title VII of the Civil Right Act of 1964 which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin – “when it intentionally fires an individual employee based in part on sex…” including sexual orientation and gender identity. “It doesn’t matter if other factors besides the plaintiff’s sex contributed to the decision,” the Court affirmed, and, for the first time, ruled that “it is impossible to discriminate against a person for being homosexual or transgender without discriminating against that individual based on sex.”

With uncharacteristic clarity, Gorsuch explained why gender identity and sexual orientation discrimination are sex discrimination:

Consider, for example, an employer with two employees, both of whom are attracted to men. The two individuals are, to the employer’s mind, materially identical in all respects, except that one is a man and the other a woman. If the employer fires the male employee for no reason other than the fact he is attracted to men, the employer discriminates against him for traits or actions it tolerates in his female colleague. Put differently, the employer intentionally singles out an employee to fire based in part on the employee’s sex, and the affected employee’s sex is a but-for cause of his discharge. Or take an employer who fires a transgender person who was identified as a male at birth but who now identifies as a female. If the employer retains an otherwise identical employee who was identified as female at birth, the employer intentionally penalizes a person identified as male at birth for traits or actions that it tolerates in an employee identified as female at birth. Again, the individual employee’s sex plays an unmistakable and impermissible role in the discharge.

That this is the right decision will be self-evident to progressives and LGBT+ advocates, so let’s focus on why this case was decided for the right reason. Read more »

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

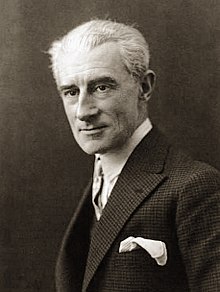

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on. Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.

Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico. The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning.

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning.

Democracy seems in bad shape these days. In contrast, its global political rivals appear to be prospering and gaining confidence in their ability to offer a viable alternative. Commenting gleefully a few weeks after Donald Trump’s election, Vladimir Putin celebrated “the degradation of the idea of democracy in western society in the political sense of the word.” Su Changhe, a Chinese scholar who has praised his country’s successes under President-for-life Xi Jinping, offers approval that “Western democracy is already showing signs of decay.” Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Prime Minister, hopes that his government will soon be “closer to its people, faster, better and more responsive” than western democracy. Since the UAE’s version of democracy is deeply rooted in local society, he claims, that dream is already being realized.

Democracy seems in bad shape these days. In contrast, its global political rivals appear to be prospering and gaining confidence in their ability to offer a viable alternative. Commenting gleefully a few weeks after Donald Trump’s election, Vladimir Putin celebrated “the degradation of the idea of democracy in western society in the political sense of the word.” Su Changhe, a Chinese scholar who has praised his country’s successes under President-for-life Xi Jinping, offers approval that “Western democracy is already showing signs of decay.” Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai and United Arab Emirates (UAE) Prime Minister, hopes that his government will soon be “closer to its people, faster, better and more responsive” than western democracy. Since the UAE’s version of democracy is deeply rooted in local society, he claims, that dream is already being realized. Idan Landau: This book develops many ideas and themes that your readers will recognize from your earlier works. Still, I sense a new, or at least a more pronounced thread of skepticism running through it—especially as regards the limits of human cognition. “Mysteriansim” is a form of skepticism, so it is no wonder that one encounters Hume in these pages much more often that one did in your earlier writings. I wonder about the roots of this shift: Is it a natural perspective one gains with old age (Ecclesiastes-style wisdom)? Or is it a well-directed response to the over-optimism you see in certain branches of theoretical cognitive science? Jerry Fodor, perhaps, has gone through a similar process of “disenchantment” with the prospects of the cognitive enterprise between his Modularity of Mind (1983) and The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way (2000). Certain things you say may strike some as a defeatist position, which cannot inspire truly groundbreaking work. After all, if we wouldn’t constantly try to push against our limits, how would we know where they are?

Idan Landau: This book develops many ideas and themes that your readers will recognize from your earlier works. Still, I sense a new, or at least a more pronounced thread of skepticism running through it—especially as regards the limits of human cognition. “Mysteriansim” is a form of skepticism, so it is no wonder that one encounters Hume in these pages much more often that one did in your earlier writings. I wonder about the roots of this shift: Is it a natural perspective one gains with old age (Ecclesiastes-style wisdom)? Or is it a well-directed response to the over-optimism you see in certain branches of theoretical cognitive science? Jerry Fodor, perhaps, has gone through a similar process of “disenchantment” with the prospects of the cognitive enterprise between his Modularity of Mind (1983) and The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way (2000). Certain things you say may strike some as a defeatist position, which cannot inspire truly groundbreaking work. After all, if we wouldn’t constantly try to push against our limits, how would we know where they are?