Dave Itzkoff in The New York Times:

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.”

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series “Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness.”

Released less than two weeks ago, the series is already a sensation, immersing viewers in the lives and rivalries of vivid subjects like Bhagavan Antle, known as Doc, the bombastic proprietor of an animal preserve and safari tour in Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Carole Baskin, an animal activist and sanctuary owner in Tampa, Fla., whose former husband disappeared in 1997. And then, of course, there’s the Tiger King himself, Joseph Maldonado-Passage, better known as Joe Exotic, a flamboyant Oklahoma zookeeper, political candidate and aspiring celebrity who was sentenced in January to 22 years in prison for his involvement in a failed plot to kill Baskin and for killing five tiger cubs. Goode, who directed “Tiger King” with Rebecca Chaiklin, said that he had been reasonably confident the series would be successful. “How can you not be fascinated with polygamy, drugs, cults, tigers, potential murder?” Goode said in an interview on Tuesday. “It had all the ingredients that one finds salacious. So we knew that there would be an appetite for it.”

But he could hardly have suspected that “Tiger King” would arrive during the coronavirus pandemic, during which audiences have had ample time to pore over its jaw-dropping plot twists while they shelter in their homes. For some viewers, “Tiger King” has also been an introduction to Goode, 62, a founder of the fabled 1980s-era New York nightspot Area who is now an owner of downtown Manhattan establishments like the Bowery Hotel and the Waverly Inn. In an interview, Chaiklin said she first worked for Goode in the mid 1990s as a door girl and manager at the Bowery Bar and Grill. More recently, over a “crazy posh dinner,” Goode first told her about the wild kingdoms they would end up traveling together.

More here.

To Jonathan Bate, Wordsworth matters principally as a prophet of nature. This may sound like what Basil Fawlty used to call a statement of the bleeding obvious. But in fact, since the Second World War scholars have more often thought about him in other terms: politically, or as a writer about psychological development, or as a central member of the ‘visionary company’ of English Romantics, the watchword for whom was not ‘Nature’ so much as ‘Imagination’. The return of nature to Wordsworthian commentary is a corollary of the environmentalist spirit of the age. The process was largely initiated by Bate himself in a book called Romantic Ecology (1991). This new book resumes the theme, providing a colourfully written celebration (one chapter is entitled ‘Lucy in the Harz with Dorothy’) of Wordsworth’s ‘radical alternative religion of nature’.

To Jonathan Bate, Wordsworth matters principally as a prophet of nature. This may sound like what Basil Fawlty used to call a statement of the bleeding obvious. But in fact, since the Second World War scholars have more often thought about him in other terms: politically, or as a writer about psychological development, or as a central member of the ‘visionary company’ of English Romantics, the watchword for whom was not ‘Nature’ so much as ‘Imagination’. The return of nature to Wordsworthian commentary is a corollary of the environmentalist spirit of the age. The process was largely initiated by Bate himself in a book called Romantic Ecology (1991). This new book resumes the theme, providing a colourfully written celebration (one chapter is entitled ‘Lucy in the Harz with Dorothy’) of Wordsworth’s ‘radical alternative religion of nature’.

The deserted streets will fill again, and we will leave our screen-lit burrows blinking with relief. But the world will be different from how we imagined it in what we thought were normal times. This is not a temporary rupture in an otherwise stable equilibrium: the crisis through which we are living is a turning point in history. The era of peak globalisation is over. An economic system that relied on worldwide production and long supply chains is morphing into one that will be less interconnected. A way of life driven by unceasing mobility is shuddering to a stop. Our lives are going to be more physically constrained and more virtual than they were. A more fragmented world is coming into being that in some ways may be more resilient.

The deserted streets will fill again, and we will leave our screen-lit burrows blinking with relief. But the world will be different from how we imagined it in what we thought were normal times. This is not a temporary rupture in an otherwise stable equilibrium: the crisis through which we are living is a turning point in history. The era of peak globalisation is over. An economic system that relied on worldwide production and long supply chains is morphing into one that will be less interconnected. A way of life driven by unceasing mobility is shuddering to a stop. Our lives are going to be more physically constrained and more virtual than they were. A more fragmented world is coming into being that in some ways may be more resilient. Do you find it as obvious as I do that Don DeLillo richly deserves to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature? And right away, as in this year?

Do you find it as obvious as I do that Don DeLillo richly deserves to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature? And right away, as in this year? Philip W. Anderson speaks in a slow, deliberate growl, pausing between sentences to ponder his next move. His basal expression, too, is deadpan. But like some exotic ceramic in an unstable state, Anderson’s mood can flip in an instant between different modes.

Philip W. Anderson speaks in a slow, deliberate growl, pausing between sentences to ponder his next move. His basal expression, too, is deadpan. But like some exotic ceramic in an unstable state, Anderson’s mood can flip in an instant between different modes. When Neil Ferguson visited the heart of British government in London’s Downing Street, he was much closer to the COVID-19 pandemic than he realized. Ferguson, a mathematical epidemiologist at Imperial College London, briefed officials in mid-March on the latest results of his team’s computer models, which simulated the rapid spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 through the UK population. Less than 36 hours later, he announced on Twitter that he had a fever and a cough. A positive test followed. The disease-tracking scientist had become a data point in his own project. Ferguson is one of the highest-profile faces in the effort to use mathematical models that predict the spread of the virus — and that show how government actions could alter the course of the outbreak. “It’s been an immensely intensive and exhausting few months,” says Ferguson, who kept working throughout his relatively mild symptoms of COVID-19. “I haven’t really had a day off since mid-January.”

When Neil Ferguson visited the heart of British government in London’s Downing Street, he was much closer to the COVID-19 pandemic than he realized. Ferguson, a mathematical epidemiologist at Imperial College London, briefed officials in mid-March on the latest results of his team’s computer models, which simulated the rapid spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 through the UK population. Less than 36 hours later, he announced on Twitter that he had a fever and a cough. A positive test followed. The disease-tracking scientist had become a data point in his own project. Ferguson is one of the highest-profile faces in the effort to use mathematical models that predict the spread of the virus — and that show how government actions could alter the course of the outbreak. “It’s been an immensely intensive and exhausting few months,” says Ferguson, who kept working throughout his relatively mild symptoms of COVID-19. “I haven’t really had a day off since mid-January.”

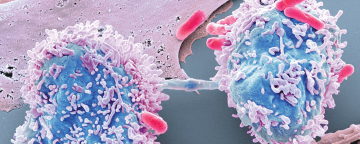

Being neither alive nor dead, nor even simply inert, a virus makes a bad enemy. How do you confront it? “We are at war,” politicians keep saying. But unlike a political opponent, the viral enemy can’t be banished or killed, or even really defeated. A virus is a vector, a force that we can only amplify or disrupt.

Being neither alive nor dead, nor even simply inert, a virus makes a bad enemy. How do you confront it? “We are at war,” politicians keep saying. But unlike a political opponent, the viral enemy can’t be banished or killed, or even really defeated. A virus is a vector, a force that we can only amplify or disrupt. Imagine you are in a small boat far, far from shore. A surprise storm capsizes the boat and tosses you into the sea. You try to tame your panic, somehow find the boat’s flimsy but still floating life raft, and struggle into it. You catch your breath, look around, and try to think what to do next. Thinking clearly is hard to do after a near-drowning experience.

Imagine you are in a small boat far, far from shore. A surprise storm capsizes the boat and tosses you into the sea. You try to tame your panic, somehow find the boat’s flimsy but still floating life raft, and struggle into it. You catch your breath, look around, and try to think what to do next. Thinking clearly is hard to do after a near-drowning experience. On autopsy, the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient can weigh as little as 30 percent of a healthy brain. The tissue grows porous. It is a sieve through which the past slips. As her mother loses her grasp on their shared history, Elizabeth Kadetsky sifts through boxes of the snapshots, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and notebooks that remain, hoping to uncover the memories that her mother is actively losing as her dementia progresses. These remnants offer the false yet beguiling suggestion that the past is easy to reconstruct—easy to hold. At turns lyrical, poignant, and alluring, The Memory Eaters tells the story of a family’s cyclical and intergenerational incidents of trauma, secret-keeping, and forgetting in the context of the 1970s and 1980s New York City. Moving from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, Kadetsky takes readers on a spiraling trip through memory, consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia.

On autopsy, the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient can weigh as little as 30 percent of a healthy brain. The tissue grows porous. It is a sieve through which the past slips. As her mother loses her grasp on their shared history, Elizabeth Kadetsky sifts through boxes of the snapshots, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and notebooks that remain, hoping to uncover the memories that her mother is actively losing as her dementia progresses. These remnants offer the false yet beguiling suggestion that the past is easy to reconstruct—easy to hold. At turns lyrical, poignant, and alluring, The Memory Eaters tells the story of a family’s cyclical and intergenerational incidents of trauma, secret-keeping, and forgetting in the context of the 1970s and 1980s New York City. Moving from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, Kadetsky takes readers on a spiraling trip through memory, consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia. From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn.

From our contemporary vantage point, voice mail may seem like a quaint artifact of the ’80s and ’90s. But the answering machine was in fact preceded by a lesser-known era of voice messaging, one which began in the early 1900s and grew out of the phonograph. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in 1877, and before he unveiled the device to the public, he spent some time colliding morphemes in a notebook. He thought he might call his invention the “antiphone” (back-talker) or the “liguphone” (clear speaker), or perhaps the “bittakophone” (parrot speaker), “hemerologophone” (speaking almanac), or “trematophone” (sound borer). In the end, Edison settled on the straightforward “phonograph,” meaning “sound writer”—an efficient summary of its mechanism. The phonograph received vibrations from the air and transcribed them as calligraphy. Sound waves would cause a needle to quiver, and the needle would etch a continuous line on a turning cylinder. If you reversed the process, the needle would travel along the groove, mining sound from the uneven topography and playing it back through a horn. One might amplify the point: it is surprising that Hegel’s aesthetic has suffered neglect in our own postmodern age, so-called, when the preeminence of the aesthetic is so marked, to the diminution of the religious, and the sterilization of the philosophical in its high idealistic ambitions. In the quarrel between the poets and the philosophers, the post-Nietzscheans have decided in favor of the poets, and one might expect the richness of Hegel’s aesthetics to be accorded some honorable place in that context. Perhaps the neglect reflects the fact that in the end Hegel places philosophy in an ultimate position in absolute spirit, and indeed seems to place the absolute spiritual significance of the aesthetic behind us. There is an element of discordance with Hegel’s proclamation of the end of art in a time when art seems to have displaced the religious in the lists of spiritual ultimacy, and philosophy itself has contented itself with being more or less an academic specialty, whether of an analytical or hermeneutical sort. Hegel is discordant in that post-Hegelian culture has tended to place in art high hopes for a suitable replacement of lost religious transcendence. It is notable even among philosophers at least in the continental tradition, that art has assumed unprecedented (sometimes metaphysical) significance: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Badiou, to name some.

One might amplify the point: it is surprising that Hegel’s aesthetic has suffered neglect in our own postmodern age, so-called, when the preeminence of the aesthetic is so marked, to the diminution of the religious, and the sterilization of the philosophical in its high idealistic ambitions. In the quarrel between the poets and the philosophers, the post-Nietzscheans have decided in favor of the poets, and one might expect the richness of Hegel’s aesthetics to be accorded some honorable place in that context. Perhaps the neglect reflects the fact that in the end Hegel places philosophy in an ultimate position in absolute spirit, and indeed seems to place the absolute spiritual significance of the aesthetic behind us. There is an element of discordance with Hegel’s proclamation of the end of art in a time when art seems to have displaced the religious in the lists of spiritual ultimacy, and philosophy itself has contented itself with being more or less an academic specialty, whether of an analytical or hermeneutical sort. Hegel is discordant in that post-Hegelian culture has tended to place in art high hopes for a suitable replacement of lost religious transcendence. It is notable even among philosophers at least in the continental tradition, that art has assumed unprecedented (sometimes metaphysical) significance: Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Adorno, Merleau-Ponty, Badiou, to name some. When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series

When he set out to investigate the inner world of exotic animal breeders, Eric Goode had no idea he would end up making the hit Netflix series  In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease. For authoritarian-minded leaders, the coronavirus crisis is offering a convenient pretext to silence critics and consolidate power. Censorship in China and elsewhere has fed the pandemic, helping to turn a potentially containable threat into a global calamity. The health crisis will inevitably subside, but autocratic governments’ dangerous expansion of power may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies.

For authoritarian-minded leaders, the coronavirus crisis is offering a convenient pretext to silence critics and consolidate power. Censorship in China and elsewhere has fed the pandemic, helping to turn a potentially containable threat into a global calamity. The health crisis will inevitably subside, but autocratic governments’ dangerous expansion of power may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies. Science costs money. And for a brief, glorious period between the start of the Manhattan Project in 1939 and the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, physics was awash in it, largely sustained by the Cold War. Things are now different, as physics — and science more broadly — has entered a funding crunch. David Kaiser, who is both a working physicist and an historian of science, talks with me about the fraught relationship between scientists and their funding sources throughout history, from Galileo and his patrons to the current rise of private foundations. It’s an interesting listen for anyone who wonders about the messy reality of how science gets done.

Science costs money. And for a brief, glorious period between the start of the Manhattan Project in 1939 and the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider in 1993, physics was awash in it, largely sustained by the Cold War. Things are now different, as physics — and science more broadly — has entered a funding crunch. David Kaiser, who is both a working physicist and an historian of science, talks with me about the fraught relationship between scientists and their funding sources throughout history, from Galileo and his patrons to the current rise of private foundations. It’s an interesting listen for anyone who wonders about the messy reality of how science gets done.