Jennifer Frazer in Scientific American:

The fire chaser beetle, as its name implies, spends its life trying to find a forest fire.

The fire chaser beetle, as its name implies, spends its life trying to find a forest fire.

Why a creature would choose to enter a situation from which all other forest creatures are enthusiastically attempting to exit is a compelling question of natural history. But it turns out the beetle has a very good reason. Freshly burnt trees are fire chaser beetle baby food. Their onlybaby food.

Fire chaser beetles are thus so hell bent on that objective that they have been known to bite firefighters, mistaking them, perhaps, for unusually squishy and unpleasant-smelling trees.

They have descended on at least one UC Berkeley football game at California Memorial Stadium — rather unfortunately situated in the midst of some recently burnt pine hills — at which an estimated 20,000 cigarettes were being smoked. The beetles’ disappointment on discovering the source of the “fire” was probably only matched by the irritation of the smokers swatting confused beetles attempting to bite their necks and hands.

More here.

The IPBES Global Assessment estimated that 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. It also documents how

The IPBES Global Assessment estimated that 1 million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction. It also documents how  Advocates of the Green New Deal say there is great urgency in dealing with the climate crisis and highlight the scale and scope of what is required to combat it. They are right. They use the term “New Deal” to evoke the massive response by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the United States government to the Great Depression. An even better analogy would be the country’s mobilization to fight World War II.

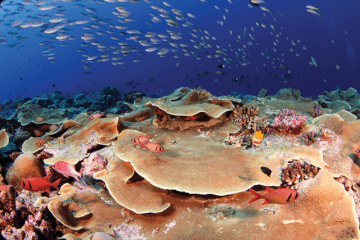

Advocates of the Green New Deal say there is great urgency in dealing with the climate crisis and highlight the scale and scope of what is required to combat it. They are right. They use the term “New Deal” to evoke the massive response by Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the United States government to the Great Depression. An even better analogy would be the country’s mobilization to fight World War II. Today, news of damaged or devastated coral reefs has become commonplace. Reefs face many threats, including bleaching, disease, overfishing, pollution and even invasive species. While the fates of the reefs may seem almost universally bleak, some scientists think the future of these vital marine ecosystems could be more complicated—and perhaps even hopeful. Ecologist

Today, news of damaged or devastated coral reefs has become commonplace. Reefs face many threats, including bleaching, disease, overfishing, pollution and even invasive species. While the fates of the reefs may seem almost universally bleak, some scientists think the future of these vital marine ecosystems could be more complicated—and perhaps even hopeful. Ecologist  One Saturday night a few months ago, a friend of mine who works in the tech industry announced the good news that she and her husband were expecting a baby. This September, they will engage in that quintessential parenting ritual: a mad dash to the hospital and the return home with their newborn. Their birth experience, however, will have a modern twist. My friend is not having the baby herself. Their new arrival will come courtesy of a female stranger whom they screened, paid and entrusted to incubate their embryo. Only after their surrogate goes into labour will they make their way to the hospital, flying from the Bay Area to southern California, where their surrogate lives and will deliver their child.

One Saturday night a few months ago, a friend of mine who works in the tech industry announced the good news that she and her husband were expecting a baby. This September, they will engage in that quintessential parenting ritual: a mad dash to the hospital and the return home with their newborn. Their birth experience, however, will have a modern twist. My friend is not having the baby herself. Their new arrival will come courtesy of a female stranger whom they screened, paid and entrusted to incubate their embryo. Only after their surrogate goes into labour will they make their way to the hospital, flying from the Bay Area to southern California, where their surrogate lives and will deliver their child. David Papineau in Aeon:

David Papineau in Aeon: Bhakti Shringarpure in Africa is Not a Country:

Bhakti Shringarpure in Africa is Not a Country:

Henry Farrell interviews Sheri Berman over at the Washington Post:

Henry Farrell interviews Sheri Berman over at the Washington Post:

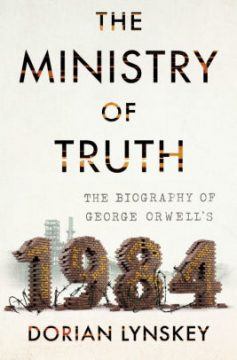

What a difference a decade makes. In 1940 George Orwell published his eighth book, the essay collection Inside the Whale, but when the Nazis in the same year drew up a list of Britons to be arrested after the planned invasion, his name wasn’t included. It was, observes Dorian Lynskey in his superb new book, ‘a kind of snub’. By the time Orwell died in January 1950, however, he was being acclaimed around the Western world as one of the great defenders of democracy and liberty, and had just been adjudged, for the first time, worthy of an entry in Who’s Who.

What a difference a decade makes. In 1940 George Orwell published his eighth book, the essay collection Inside the Whale, but when the Nazis in the same year drew up a list of Britons to be arrested after the planned invasion, his name wasn’t included. It was, observes Dorian Lynskey in his superb new book, ‘a kind of snub’. By the time Orwell died in January 1950, however, he was being acclaimed around the Western world as one of the great defenders of democracy and liberty, and had just been adjudged, for the first time, worthy of an entry in Who’s Who. A

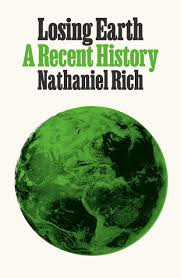

A Forty years ago, Nathaniel Rich tells us in Losing Earth, global warming was better understood by the general public and US politicians than at any time since. Moreover, the opportunity to broker a global treaty to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases had presented itself, and the political will existed for the US to lead on the issue. Had action been taken, we could have stopped climate change in its tracks, much as we halted ozone depletion with the 1989 Montreal Protocol to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Forty years ago, Nathaniel Rich tells us in Losing Earth, global warming was better understood by the general public and US politicians than at any time since. Moreover, the opportunity to broker a global treaty to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases had presented itself, and the political will existed for the US to lead on the issue. Had action been taken, we could have stopped climate change in its tracks, much as we halted ozone depletion with the 1989 Montreal Protocol to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). As Speaker of the House

As Speaker of the House  You know a book has entered your bloodstream when the ground beneath your feet, once viewed as bedrock, suddenly becomes a roof to unknown worlds below. The British writer

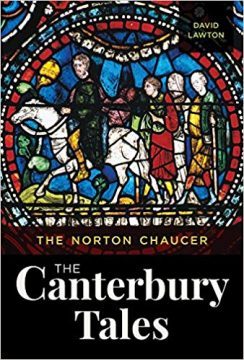

You know a book has entered your bloodstream when the ground beneath your feet, once viewed as bedrock, suddenly becomes a roof to unknown worlds below. The British writer  Today we’re going to discuss the Canterbury Tales. You’ve just written a biography of Geoffrey Chaucer. What would someone learn from your biography about Chaucer that they might not have known before?

Today we’re going to discuss the Canterbury Tales. You’ve just written a biography of Geoffrey Chaucer. What would someone learn from your biography about Chaucer that they might not have known before?