by Samia Altaf

Last night I dreamed I was on my way to the tailor’s in the H-Block market to pick up the outfit that Mrs. Obama was to wear at President Obama’s second inauguration. The State Department official who was to transport it in the diplomatic pouch was on the tarmac waiting in the military plane with its engines revving. Everything was set.

But real life is unpredictable and the best laid plans of mice and men, and women too, can get derailed. As I skirted the roundabout to go north, traffic stalled in the circle of Lalikjan Chowk. A crowd of bearded and turbaned men, their trouser-ends hoisted above the ankles, was milling around, waving their arms and shouting, their teeth gleaming white through their black beards. Some energetic ones, skinny and intense, also with black floating beards, were rerouting the traffic advising the cars to turn back. That I could not afford to do. This was a mission-critical errand—the first lady was to wear the outfit in the morning and it was already night in Washington, D.C. All I had was the ten-hour time difference in Lahore.

I figured it was a religious demonstration, one faction of Muslims upset at another’s manner of dressing or eating or laughing or standing. Then I saw saw women and children holding placards protesting power failures and the increased cost of the whatever little electric supply that came their way for couple of hours in the day. Keep your focus I told myself, circling around, zigzagging through the utility shops on the left of the roundabout, past the back wall of the S-Block graveyard, navigating the Z-Block bylanes across from the padlocked library, lurching over the empty lot behind the big mosque to finally arrive at the complex housing the tailoring shop. Read more »

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

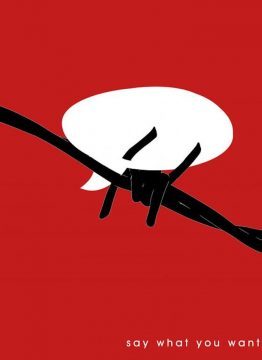

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision?

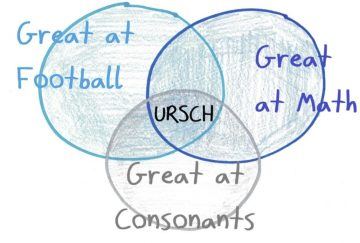

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision? Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive.

Three seasons in the NFL? Impressive. There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of

There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of  Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city.

Mosul’s old city lies in ruins. A major section of the third largest city in Iraq has been destroyed by war. Two years after the Iraqi government and the United States-led coalition recaptured it from ISIS, the city is still noticeably scarred. Many residents have fled, or are detained in camps elsewhere in the country. Those who have returned live amid the ruins of their old houses and their old lives. But what is being reconstructed is cultural heritage. UNESCO has worked with the Iraqi government to launch a campaign called ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’, focusing on a handful of historic monuments in the city. The United Arab Emirates has pledged $50 million to rebuild the 850-year-old al-Nuri mosque and its minaret, known as al-Hadba (or the hunchback), a symbol of the city. S

S Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the

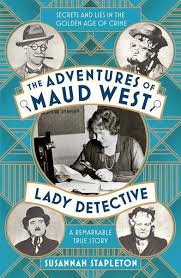

Could a blood test detect cancer in healthy people? Grail, a Menlo Park, Calif.-based company, has raised $1.6 billion in venture capital to prove the answer is yes. And at the world’s largest meeting of cancer doctors, the company is unveiling data that seem designed to assuage the concerns and fears of its doubters and critics. But outside experts emphasize there is still a long way to go. The data, from a pilot study that Grail is using to develop its diagnostic before running it through the gantlet of two much larger clinical trials, are being presented Saturday in several poster sessions at the  Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers.

Unconventional lives can tell us much about the conventions and social currents of their times. Susannah Stapleton’s compulsively absorbing book about Maud West centres on a woman who was a splendid one-off and yet somehow entirely of her age. It is not quite a biography and not quite a personal quest, but a bit of both. Tracking her quarry through the last decades of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, Stapleton found that West eluded her at every turn. The bewildering array of red herrings, dead ends, fibs, disguises, half-truths and plain deceptions she encountered becomes the story not only of West herself but also of the world in which she lived. The 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of British detective fiction and many of its most famous authors were women. Maud West, with her magnifying glass and her box of disguises, could have been a character in a Dorothy L Sayers novel – and in fact, she seemed to have lived her life as though it were a continually unfolding story, complete with cloaks and daggers. The history of philosophy usually tells us how one set of ideas gave birth to another. What it tends to overlook are the political forces and social upheavals that shaped them. Witcraft, by contrast, sees philosophy itself as a historical practice. For much of its career, it was never easy to distinguish from political conflict, religious strife and scientific controversy. For some 17th-century Puritans, philosophy was a satanic pursuit, an impious meddling with sacred truths. There was a battle between the church and the universities on the one hand, with their reverence for Aristotle and the schoolmen, and on the other the humanists, scientists, atheists and radicals. It is the stuffy old university of Wittenberg versus the humanistic Hamlet and his sceptical friend Horatio.

The history of philosophy usually tells us how one set of ideas gave birth to another. What it tends to overlook are the political forces and social upheavals that shaped them. Witcraft, by contrast, sees philosophy itself as a historical practice. For much of its career, it was never easy to distinguish from political conflict, religious strife and scientific controversy. For some 17th-century Puritans, philosophy was a satanic pursuit, an impious meddling with sacred truths. There was a battle between the church and the universities on the one hand, with their reverence for Aristotle and the schoolmen, and on the other the humanists, scientists, atheists and radicals. It is the stuffy old university of Wittenberg versus the humanistic Hamlet and his sceptical friend Horatio. Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review:

Quinn Slobodian in Boston Review: