Scott Alexander in Slate Star Codex:

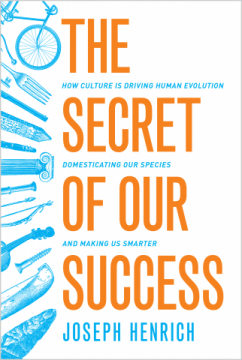

“Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis. The Secret Of Our Success by anthropologist Joseph Henrich manages to be an amazing book anyway.

“Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis. The Secret Of Our Success by anthropologist Joseph Henrich manages to be an amazing book anyway.

Henrich wants to debunk (or at least clarify) a popular view where humans succeeded because of our raw intelligence. In this view, we are smart enough to invent neat tools that help us survive and adapt to unfamiliar environments.

Against such theories: we cannot actually do this. Henrich walks the reader through many stories about European explorers marooned in unfamiliar environments. These explorers usually starved to death. They starved to death in the middle of endless plenty. Some of them were in Arctic lands that the Inuit considered among their richest hunting grounds. Others were in jungles, surrounded by edible plants and animals. One particularly unfortunate group was in Alabama, and would have perished entirely if they hadn’t been captured and enslaved by local Indians first.

These explorers had many advantages over our hominid ancestors. For one thing, their exploration parties were made up entirely of strong young men in their prime, with no need to support women, children, or the elderly. They were often selected for their education and intelligence.

More here.

They called it the épuration sauvage, the wild purge, because it was spontaneous and unofficial. But, yes, it was savage, too. In the weeks and months following the

They called it the épuration sauvage, the wild purge, because it was spontaneous and unofficial. But, yes, it was savage, too. In the weeks and months following the  Mendelssohn’s Wiki page says his grave has been reconstructed. Not surprising: grand historical narratives are everywhere legible in Berlin’s built environment. The Jewish cemetery where he’s buried became part of East Berlin after the war, falling into even further disrepair after the Nazi years. His grave, as well as many others, was only reconstructed in the 2000s.

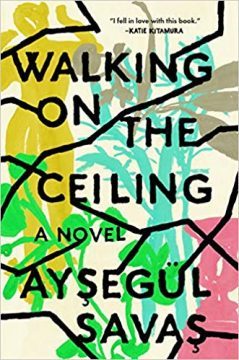

Mendelssohn’s Wiki page says his grave has been reconstructed. Not surprising: grand historical narratives are everywhere legible in Berlin’s built environment. The Jewish cemetery where he’s buried became part of East Berlin after the war, falling into even further disrepair after the Nazi years. His grave, as well as many others, was only reconstructed in the 2000s. In a 2017 essay for the magazine Fare, Ayşegül Savaş described a game she played as a high school student in Istanbul. She and a friend strapped on backpacks and pretended to be foreigners in Istanbul’s tourist quarter. The purpose of “the tourist game,” Savaş remembered, “was to talk to people in English of varying accents, throwing in a handful of mispronounced Turkish words.” They asked locals for directions to Istanbul landmarks, had their pictures taken in front of palaces and felt “overjoyed when our identities were not revealed, all the more if anyone showed an interest in us and asked where we were from.” The game, Savaş explained, “made us feel like we were in control while giving us the freedom to explore as we pleased; our city took on new wonder when viewed from the imaginary foreign gaze.”

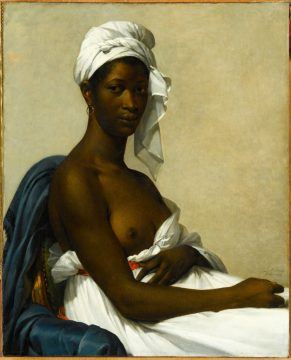

In a 2017 essay for the magazine Fare, Ayşegül Savaş described a game she played as a high school student in Istanbul. She and a friend strapped on backpacks and pretended to be foreigners in Istanbul’s tourist quarter. The purpose of “the tourist game,” Savaş remembered, “was to talk to people in English of varying accents, throwing in a handful of mispronounced Turkish words.” They asked locals for directions to Istanbul landmarks, had their pictures taken in front of palaces and felt “overjoyed when our identities were not revealed, all the more if anyone showed an interest in us and asked where we were from.” The game, Savaş explained, “made us feel like we were in control while giving us the freedom to explore as we pleased; our city took on new wonder when viewed from the imaginary foreign gaze.” For a long time, and even very recently, artworks with black models—or by black artists—were collected sparingly by museums, in part because they weren’t considered to fit into any standard art-historical narratives. Between 2008 and 2018, for instance, only 2.4 percent of purchases and donations in thirty of the best-known American museums were works by African American artists, according to an analysis by In Other Words and ARTNews. Only 7.6 percent of exhibitions concerned African American artists. From Modernism through postwar Abstract Expressionism, work by black painters still represented a catch-22: they were either too much about the black experience and thus didn’t seem to fit into the European timeline of art history, or they were too reliant on the abstract when the few museums that did collect black artists wanted figurative works that represented “the black experience.” “It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work,” said Ann Temkin, the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a recent

For a long time, and even very recently, artworks with black models—or by black artists—were collected sparingly by museums, in part because they weren’t considered to fit into any standard art-historical narratives. Between 2008 and 2018, for instance, only 2.4 percent of purchases and donations in thirty of the best-known American museums were works by African American artists, according to an analysis by In Other Words and ARTNews. Only 7.6 percent of exhibitions concerned African American artists. From Modernism through postwar Abstract Expressionism, work by black painters still represented a catch-22: they were either too much about the black experience and thus didn’t seem to fit into the European timeline of art history, or they were too reliant on the abstract when the few museums that did collect black artists wanted figurative works that represented “the black experience.” “It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work,” said Ann Temkin, the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a recent  If scientists want to simulate a brain that can match human intelligence, let alone eclipse it, they may have to start with better building blocks—computer chips inspired by our brains. So-called neuromorphic chips replicate the architecture of the brain—that is, they talk to each other using “neuronal spikes” akin to a neuron’s action potential. This spiking behavior allows the chips to consume very little power and remain power-efficient even when tiled together into very large-scale systems. “The biggest advantage in my mind is scalability,” says

If scientists want to simulate a brain that can match human intelligence, let alone eclipse it, they may have to start with better building blocks—computer chips inspired by our brains. So-called neuromorphic chips replicate the architecture of the brain—that is, they talk to each other using “neuronal spikes” akin to a neuron’s action potential. This spiking behavior allows the chips to consume very little power and remain power-efficient even when tiled together into very large-scale systems. “The biggest advantage in my mind is scalability,” says

The question of what kinds of physical systems are conscious “is one of the deepest,

The question of what kinds of physical systems are conscious “is one of the deepest,  Granted, the U.S. was by this point pretty much dead to me, as I had determined from periodic visits that it was in the interest of my sanity to avoid the country altogether. Frida Kahlo once observed: “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste. They are boring, and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”And yet this, perhaps, is the least of the problems.

Granted, the U.S. was by this point pretty much dead to me, as I had determined from periodic visits that it was in the interest of my sanity to avoid the country altogether. Frida Kahlo once observed: “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste. They are boring, and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”And yet this, perhaps, is the least of the problems. Mistrust all enterprises that require new clothes,” says EM Forster in A Room With a View, adapting a quote from

Mistrust all enterprises that require new clothes,” says EM Forster in A Room With a View, adapting a quote from  In addition to resources, the advocates of cultured meat have a philosophy ready to hand. Many of them are self-described utilitarians, readers of the works of philosopher Peter Singer, in particular his 1975 book

In addition to resources, the advocates of cultured meat have a philosophy ready to hand. Many of them are self-described utilitarians, readers of the works of philosopher Peter Singer, in particular his 1975 book  The painting made headlines last November for the price it took at auction, though this datum doesn’t interest me. More significant is the return of a too-little-revived film that documents Portrait of an Artist’s charged iterations and the circumstances surrounding them. After watching A Bigger Splash a few weeks before its premiere at Cannes in 1974, Hockney said he was “utterly shattered” by it, his anguish spiked further by a film-director friend who favorably—if somewhat incongruously—likened it to “a real Sunday Bloody Sunday,” John Schlesinger’s astute, London-set, big-studio-backed 1971 drama about a love triangle (two men, one woman). More felicitous comparisons might include Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand (1971), a gay XXX landmark in which a Fire Island natatorium becomes a pleasure palace, not to mention Robert Kramer’s Milestones (1975), an epic dirge on the failed dreams of the New Left in the US, which was also devised as a docufiction. (Hazan and Mingay would return to this genre with 1980’s Rude Boy, centering on the Clash.) But as for movies about making (art) and unmaking (a relationship), I can think of none better, or more sinuous—as serpentine as Hockney’s enunciation of a favorite descriptor.

The painting made headlines last November for the price it took at auction, though this datum doesn’t interest me. More significant is the return of a too-little-revived film that documents Portrait of an Artist’s charged iterations and the circumstances surrounding them. After watching A Bigger Splash a few weeks before its premiere at Cannes in 1974, Hockney said he was “utterly shattered” by it, his anguish spiked further by a film-director friend who favorably—if somewhat incongruously—likened it to “a real Sunday Bloody Sunday,” John Schlesinger’s astute, London-set, big-studio-backed 1971 drama about a love triangle (two men, one woman). More felicitous comparisons might include Wakefield Poole’s Boys in the Sand (1971), a gay XXX landmark in which a Fire Island natatorium becomes a pleasure palace, not to mention Robert Kramer’s Milestones (1975), an epic dirge on the failed dreams of the New Left in the US, which was also devised as a docufiction. (Hazan and Mingay would return to this genre with 1980’s Rude Boy, centering on the Clash.) But as for movies about making (art) and unmaking (a relationship), I can think of none better, or more sinuous—as serpentine as Hockney’s enunciation of a favorite descriptor. Written in the sharp and irate debunking-of-bad-science mode that has become his stock-in-trade, Warner’s book The Truth About Fat reveals that many of the most widely accepted views on the causes of obesity are simplistic, scientifically unsound or immoral. The book is a thought-provoking corrective to the idea that obesity is simply the result of eating too much and moving too little, which puts the blame squarely on the obese. With verve, mastery of the available data, and a gripping narrative, Warner demonstrates that obesity is a highly complicated problem that requires intricate strategies if it is to be addressed effectively. Books that take a complexity-theory approach are not normally an easy sell, given that they refuse to provide neat solutions to pressing problems, and Warner’s certainly pulls the rug of comforting certainties from under the reader’s feet. Almost all existing strategies in the fight against obesity are flawed and inefficient at best, he says, and may even be making things worse.

Written in the sharp and irate debunking-of-bad-science mode that has become his stock-in-trade, Warner’s book The Truth About Fat reveals that many of the most widely accepted views on the causes of obesity are simplistic, scientifically unsound or immoral. The book is a thought-provoking corrective to the idea that obesity is simply the result of eating too much and moving too little, which puts the blame squarely on the obese. With verve, mastery of the available data, and a gripping narrative, Warner demonstrates that obesity is a highly complicated problem that requires intricate strategies if it is to be addressed effectively. Books that take a complexity-theory approach are not normally an easy sell, given that they refuse to provide neat solutions to pressing problems, and Warner’s certainly pulls the rug of comforting certainties from under the reader’s feet. Almost all existing strategies in the fight against obesity are flawed and inefficient at best, he says, and may even be making things worse. I’m not sure the opinion of your adolescent self is the surest moral polestar. You make most of the biggest decisions in life, the ones that’ll determine its trajectory for the next decades — what you want to do, where you’ll go to college, who you’ll marry — when you have the least amount of data to base them on, and not the vaguest understanding of what their real-life implications will be.

I’m not sure the opinion of your adolescent self is the surest moral polestar. You make most of the biggest decisions in life, the ones that’ll determine its trajectory for the next decades — what you want to do, where you’ll go to college, who you’ll marry — when you have the least amount of data to base them on, and not the vaguest understanding of what their real-life implications will be.  In 1920, the U.S. introduced a nationwide ban on alcohol by passing the Eighteenth Amendment. It lated reconsidered and repealed the ban in 1933 with the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment.

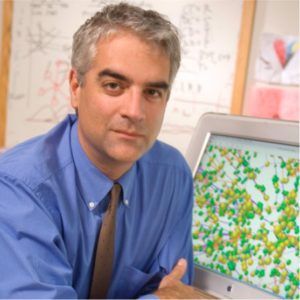

In 1920, the U.S. introduced a nationwide ban on alcohol by passing the Eighteenth Amendment. It lated reconsidered and repealed the ban in 1933 with the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment. It’s easy to be cynical about humanity’s present state and future prospects. But we have made it this far, and in some ways we’re doing better than we used to be. Today’s guest, Nicholas Christakis, is an interdisciplinary researcher who studies human nature from a variety of perspectives, including biological, historical, and philosophical. His most recent book is

It’s easy to be cynical about humanity’s present state and future prospects. But we have made it this far, and in some ways we’re doing better than we used to be. Today’s guest, Nicholas Christakis, is an interdisciplinary researcher who studies human nature from a variety of perspectives, including biological, historical, and philosophical. His most recent book is