Month: May 2019

David Winters (1939 – 2019)

Democrats, Fight now or surrender

Chauncey Devega in Salon:

If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” as an old piece of political folk wisdom holds. The Democratic Party has apparently not learned this lesson. This is why (among other reasons) Donald Trump will likely defeat the Democratic nominee — whoever that may be — and win the 2020 presidential election. On Wednesday, Attorney General William Barr testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee about his handling of special counsel Robert Mueller’s report about obstruction of justice and Donald Trump and his inner circle’s collusion with Russia.

If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything,” as an old piece of political folk wisdom holds. The Democratic Party has apparently not learned this lesson. This is why (among other reasons) Donald Trump will likely defeat the Democratic nominee — whoever that may be — and win the 2020 presidential election. On Wednesday, Attorney General William Barr testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee about his handling of special counsel Robert Mueller’s report about obstruction of justice and Donald Trump and his inner circle’s collusion with Russia.

Barr again showed himself to be Donald Trump’s henchman and a man who does not serve the American people or the rule of law. In that role, Barr basically argued that Donald Trump is a king who is above the law; repeatedly lied and misrepresented Mueller’s findings; deflected what Mueller in (now) two separate letters has communicated as serious concerns about how Barr distorted the findings of the Trump-Russia investigation; and in total sullied the office of the attorney general and the Department of Justice. Barr and the Trump regime have contempt for basic democratic norms such as checks and balances. As such, Barr refused to testify before the House Judiciary Committee on Thursday. Political consultant David Rothkopf described the importance of Barr’s testimony before the Senate this way:

I don’t think we fully realize the profundity of Barr’s assertions yesterday. The ideas that a president can determine whether or not he ought to be investigated or that a president is incapable of committing obstruction are not just outrageous assaults on Constitutional values.

Taken in the context of this administration’s systematic rejection of the oversight role of Congress and of the law — whether it is the emoluments clause of the Constitution or the obligation of the IRS to hand over tax returns to the Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee — what we are seeing is nothing less than a coup, to use a word the president has grown fond of. Trump and Barr are seeking to eliminate the checks and balances that are a hallmark of our system and to effectively render the Congress subservient to the presidency.

This was less a story of the Democrats forcing Barr out of the shadows and shaming the devil than of Barr showing the world, out of his own hubris, who he really is — Trump’s vassal and human puppet. How did Senate Democrats respond to this? With somewhat flummoxed but generally polite annoyance. There was little if any fury and fire given Barr’s behavior and the threat to American democracy he represents.

More here.

Who wins from public debate? Liars, bullies and trolls

Steven Poole in The Guardian:

When Jordan Peterson and Slavoj Žižek met a fortnight ago in Toronto to do battle on the theme “Happiness: Capitalism v Marxism”, it cost US$14.95 (£11.60) to watch online, and touts were selling tickets for hundreds of dollars. Peterson, not having found time to read any of Žižek’s books, launched instead into an attack on The Communist Manifesto. In response, Žižek riffed about China, Trump, liberals, antisemitism and cheese. In the end, both men agreed that well-regulated capitalism was a good thing. It was billed as the “debate of the century”, and in a way it might as well have been: it was a perfect, if mostly harmless, illustration of why debate itself is such a bad idea.

When Jordan Peterson and Slavoj Žižek met a fortnight ago in Toronto to do battle on the theme “Happiness: Capitalism v Marxism”, it cost US$14.95 (£11.60) to watch online, and touts were selling tickets for hundreds of dollars. Peterson, not having found time to read any of Žižek’s books, launched instead into an attack on The Communist Manifesto. In response, Žižek riffed about China, Trump, liberals, antisemitism and cheese. In the end, both men agreed that well-regulated capitalism was a good thing. It was billed as the “debate of the century”, and in a way it might as well have been: it was a perfect, if mostly harmless, illustration of why debate itself is such a bad idea.

We are told debate is the great engine of liberal democracy. In a free society, ideas should do battle in the public forum. Those who seek to lead us should debate with one another, and this will help us make the best possible informed judgments. Schoolchildren should be taught debating skills to better prepare them for the intellectual cut-and-thrust of the adult world. The rise in formal debating events such as those organised by Intelligence Squared enables citizens to better understand complex problems. People whose views we find abhorrent should not be ignored. We should debate with them, and so point out the flaws in the arguments. The more we debate, the happier and more civilised we will be.

That’s the theory, anyway. In practice, modern debate has a structural bias in favour of demagoguery and disinformation. It inherently favours liars. There is no cost to, and much potential advantage in, taking the low road and indulging in bullying and personal attack. There’s a reason why we talk about “point-scoring” in debates, and it is because we think of a debate as like a boxing match: it’s a competition rather than a collaboration. (If you can bear it, you can watch online a 2005 debate between Christopher Hitchens and George Galloway on the Iraq war: the result was that everyone lost.) In a recent Pew poll, just a quarter of Americans agreed that “the tone of debate among political leaders is respectful”.

More here.

When Did Pop Culture Become Homework?

Soraya Roberts in Longreads:

Soraya Roberts in Longreads:

I didn’t do my homework last weekend. Here was the assignment: Beyoncé’s Homecoming — a concert movie with a live album tie-in — the biggest thing in culture that week, which I knew I was supposed to watch, not just as a critic, but as a human being. But I didn’t. Just like I didn’t watch the premiere of Game of Thrones the week before, or immediately listen to Lizzo’s Cuz I Love You. Instead, I watched something I wanted to: RuPaul’s Drag Race. What worse place is there to hide from the demands of pop culture than a show about drag queens, a set of performance artists whose vocabulary is almost entirely populated by celebrity references? In the third episode of the latest season, Vietnamese contestant Plastique Tiara is dragged for her uneven performance in a skit about Mariah Carey, and her response shocks the judges. “I only found out about pop culture about, like, three years ago,” she says. To a comically sober audience, she then drops the biggest bomb of all: “I found out about Beyoncé legit four years ago.” I think Michelle Visage’s jaw might still be on the floor.

“This is where you all could have worked together as a group to educate each other,” RuPaul explains. It is the perfect framing of popular culture right now — as a rolling curriculum for the general populace which determines whether you make the grade as an informed citizen or not. It is reminiscent of an actual educational philosophy from the 1930s, essentialism, which was later adopted by E.D. Hirsch, the man who coined the term “cultural literacy” as “the network of information that all competent readers possess.” Essentialist education emphasizes standardized common knowledge for the entire population, which privileges the larger culture over individual creativity. Essentialist pop culture does the same thing, flattening our imaginations until we are all tied together by little more than the same vocabulary.

More here.

John Huston’s Train Wreck

Melissa Anderson at Bookforum:

First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently.

First published in 1952, Lillian Ross’s Picture, an eyewitness report of director John Huston’s adaptation of The Red Badge of Courage, remains the paradigm of a slim genre, the nonfiction account of a movie’s making (and unmaking): from shooting to editing to studio meddling to publicity planning to preview screening to more studio meddling to, finally, theatrical release. The book is populated by raffish heroes (Huston) and tyrannical philistines (Louis B. Mayer), by the beleaguered (producer Gottfried Reinhardt) and the overweening (MGM head of production Dore Schary), and by various hypocrites, toadies, greenhorns, and wives. Envisioned by Ross as “a fact piece in novel form, or maybe a novel in fact form,” Picture endures as a key work of proto–New Journalism. Though Ross, a writer for more than sixty years at the New Yorker—where Picture, under the title “Production Number 1512,” was first published, in five installments—was renowned for her fly-on-the-wall reporting, she is not always invisible in the book; “I” pops up intermittently.

more here.

Diane Arbus: An Illusion of Access

Mark Prince at the TLS:

In the era of Instagram and YouTube, when photography has mostly become a means of projecting oneself into the world to gauge its reaction, it takes an imaginative leap to recognize how revolutionary Diane Arbus’s murky photographs of some of the more disturbing corners of New York life must have looked back in the late 1950s, when they first appeared. Before her, photographers who wanted to be artists strove for impartiality, as if the camera were the eye of a stern god. Photographing passersby, they might tuck a camera into an overcoat to conceal from the subject (and viewer) the exchange being enacted between seeing and being seen. Arbus changed all this, taking pictures that record a direct encounter between photographer and stranger, and in so doing transformed a documentary medium, which had evolved out of the myth of its own objectivity, into a meeting of two pairs of eyes, with the lens standing in for one of the pairs. We never see her, but her presence, as an implicated observer, is everywhere apparent. These are pictures which never claim we can assume their images apply to any other viewpoint than her own.

In the era of Instagram and YouTube, when photography has mostly become a means of projecting oneself into the world to gauge its reaction, it takes an imaginative leap to recognize how revolutionary Diane Arbus’s murky photographs of some of the more disturbing corners of New York life must have looked back in the late 1950s, when they first appeared. Before her, photographers who wanted to be artists strove for impartiality, as if the camera were the eye of a stern god. Photographing passersby, they might tuck a camera into an overcoat to conceal from the subject (and viewer) the exchange being enacted between seeing and being seen. Arbus changed all this, taking pictures that record a direct encounter between photographer and stranger, and in so doing transformed a documentary medium, which had evolved out of the myth of its own objectivity, into a meeting of two pairs of eyes, with the lens standing in for one of the pairs. We never see her, but her presence, as an implicated observer, is everywhere apparent. These are pictures which never claim we can assume their images apply to any other viewpoint than her own.

more here.

Angels: Visible and Invisible

Alexander Larman at The Guardian:

In our increasingly secular age, it comes as a shock to discover that one in three people believe in the existence of angels. This is attributed more to the egocentric idea that we have a “guardian angel” watching over us, ready to intervene in our ill fortune, rather than any wider appreciation of angelology.

In our increasingly secular age, it comes as a shock to discover that one in three people believe in the existence of angels. This is attributed more to the egocentric idea that we have a “guardian angel” watching over us, ready to intervene in our ill fortune, rather than any wider appreciation of angelology.

Peter Stanford’s thorough and engaging study recognises the way in which popular culture – from Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North sculpture to the messengers in the films It’s a Wonderful Life and Wings of Desire – portrays angels as present within our own lives. This may be because they are possessed of a secular accessibility that makes them easier to believe in than other supernatural beings. As Stanford acknowledges, when Robbie Williams sang “I’m loving angels instead” on his 1997 hit Angels, he was not doing so in the context of religious belief, but in the universally applicable form of a love song.

more here.

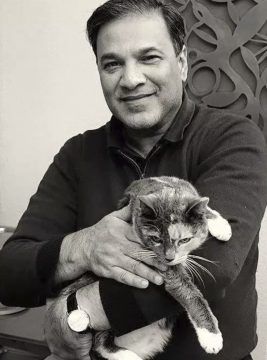

Fredrik Weibull interviews Abbas Raza

From ANOW:

In this episode Fred Weibull interviewed Abbas to learn about the origins and intentions of 3QD, the reasons behind its extraordinary commitment to public service and the emphasis on the art of curation over content production. Abbas expands on 3QD’s process of locating and discerning content, about the organisation of the editorial team, scattered across the world and the particular work discipline and practices of a skilled curator…

In this episode Fred Weibull interviewed Abbas to learn about the origins and intentions of 3QD, the reasons behind its extraordinary commitment to public service and the emphasis on the art of curation over content production. Abbas expands on 3QD’s process of locating and discerning content, about the organisation of the editorial team, scattered across the world and the particular work discipline and practices of a skilled curator…

Now in its 15th year 3 quarks daily occupies an interesting place in the world of ideas, which belongs neither to the intellectual establishment institutions nor its commercial media counterpart. Yet it is frequented by the intellectual elite, indicated by endorsements from the thinking world’s upper echelon…

More here.

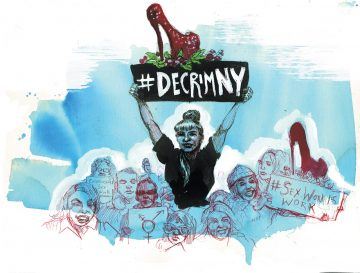

It’s Not About Sex

Molly Crabapple in the NY Review of Books:

American sex workers are today more organized, and more oppressed, than they have been in years. Last year the US government passed the twin laws of SESTA and FOSTA—the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, respectively, which have closed online spaces where sex workers found clients and shared information—forcing them to work with pimps or to work on the streets where they may be beaten and murdered. Sex workers have responded with ferocious activism. Collectives like Survivors Against SESTA and the Sex Workers Project are lobbying, marching, and canvassing to overturn these laws. More surprisingly, Democratic politicians like New York state senators Jessica Ramos and Julia Salazar have listened to them, canvassed with them, and even promised to introduce laws to decriminalize prostitution.

On February 22 sex trafficking made its way into the headlines when New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft, a billionaire septuagenarian and Trump crony, was arrested during a series of prostitution stings on massage parlors in three Florida counties and charged with two misdemeanor counts of soliciting prostitution. During the seven months police spent investigating the parlors, they secretly installed cameras in massage rooms and made videos of the women as they gave handjobs to their customers. The Vero County police department refused to answer questions from sex workers’ rights advocate Kate D’Adamo as to whether their officers had had sexual contact with any of these women in the course of their investigation, but one detective confirmed to the sports website Deadspin that he had.

Police described the investigation as an anti-trafficking operation, but no trafficking charges have been made. Four women who ran the massage parlors were arrested. Among other crimes, they were all charged with prostitution. All of them have spent more time in jail than any of the men they allegedly serviced.

More here.

The Origins of European Neoliberalism

Nicholas Mulder in n+1:

Where most of the charges that the right levels against the EU are hard to take seriously, the left has produced cogent and sophisticated critiques of the organization. Leftist skepticism about the project of integration goes back to the beginnings of the European Economic Community, but was generally a minority current; the Eurozone economic crisis and Britain’s ongoing attempts to depart from the EU have reanimated this tradition, with some arguing for a left exit, or “Lexit.” The Lexit position points to a split among the Union’s left-wing critics: varying diagnoses of the EU’s democratic deficit and neoliberal bias in turn suggest different paths to a more progressive and democratic Europe.

Currently, there are two broad varieties in left-wing anti-Europeanism. The first line of criticism is that the EU is an unaccountable technocracy constitutionally opposed to democracy. On this reading, unelected Eurocrats at the European Commission threaten national sovereignty as they enforce budgetary rules, laws, and regulations with no accountability. A related but distinct accusation is that the EU is terrible for national democracy because it is a vehicle for German empire. On this reading, the technocrats are either simply doing the Germans’ bidding, or else the Germans are responsible for long ago having rigged the rules of the union in favor of the continent’s largest and most powerful country.

These left-wing analyses focus on a real problem: the constraints of current EU and Eurozone economic policies, which have deepened and prolonged the continent’s crisis. Yet in their urge to counter the tyranny of the market, left nationalists misread the nature of the neoliberal project in European politics.

More here.

Must We Mean What We Say?: On the Life and Thought of Stanley Cavell

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books:

Marshall Cohen in The LA Review of Books:

THE BOUNTIFULLY GIFTED Stanley Cavell was unique among American philosophers of his generation in the range of his philosophical, cultural, and artistic interests. He resisted the split between Anglophone and Continental traditions that has characterized post-Kantian philosophy, writing with distinction about epistemology and aesthetics, Emerson and Thoreau, Shakespearean tragedy and Hollywood comedy, as well as about modernism in film and music. Modernist works, he believed, divide audiences into insiders and outsiders, create unpleasant cults, and demand for their reception the shock of conversion. Such works are not easily received, as Cavell, who regarded himself as a modernist writer, painfully discovered. Many features of his writing have been found troublesome and even offensive by a significant number of readers. I believe these features are not an expression of modernist impulses but rather manifestations of personal idiosyncrasies that Cavell’s autobiographical reflections, in his 2010 book, Little Did I Know: Excerpts from Memory, can help us to understand, if not accept.

Little Did I Know obeys a double time scheme. It comprises a series of entries presented in their order of composition from July 2, 2003, to September 1, 2004. The depicted events reporting Cavell’s Emersonian journey occur in loose chronological order, interrupted by philosophical meditations, portraits of friends, and editorial comments about the original drafted entries. The formal arrangement honors the fundamental importance granted to the time and context of utterance in the work of J. L. Austin and the late Wittgenstein. The depictions allow Cavell to exploit techniques reminiscent of psychoanalysis (free association) and film (flashbacks and flash forwards, jump cuts, close-ups, and montage). And modernism’s experimental departures from traditional narrative facilitate his representation of philosophy as an abstraction of biography.

More here.

Saturday Poem

On Entering Elysium

On entering Elysium, Erato gives us a key

to the library of poems we did not write.

It is a moment of unbearable sadness. Some

refuse it. Some take the key, but never try

the lock. Some enter, find a chair and fall asleep.

Most shelves hold the dreams to didn’t remember,

or remembered for a while, but didn’t write down.

Next, shelf after shelf of journals of days unwritten,

not remembered, ideas that came so fast, a blink

blew them away, and the bits and pieces, poems even,

from your unopened or lost journals, and a little corner

for the few that found their way into the world.

At the end, waits the shelf of great poems you didn’t

have the confidence, courage, or ambition to attempt.

by Nils Peterson

from All the Marvelous Stuff

Caesura Editions, 2019

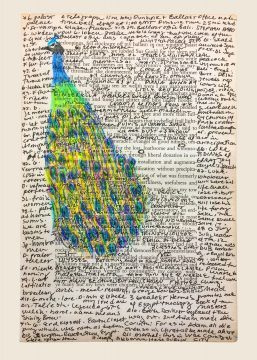

Finnegan’s Wake at 80: In Defense of the Difficult

Susie Lopez at Lit Hub:

The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this?

The Wake has been called “the most colossal leg pull in literature” and even Joyce’s patron fell out with him over it. But Wake scholarship is thriving more than ever. In the words of Joyce Scholar Sam Slote almost “any analysis will be incomplete.” After Ulysses, Joyce was interested in the subconscious interior monologue, our dreaming lives. He also wanted to shatter the conventions of language to form an almost eternal every-language. It sounds somewhat like the dial of a radio in Joyce’s time, static turning into myriad languages. Joyce intentionally made passages more obscure to evoke radio. PHD candidate Yuta Imazeki has calculated “numbers of portmanteaux and foreign words in the radio passage” that are higher in frequency than any others; intentionally obscure. So is it an indecipherable ruse or a harbinger of hypertext? Could it even be… therapeutic? As a self-taught enthusiast, how did I even get into this?

more here.

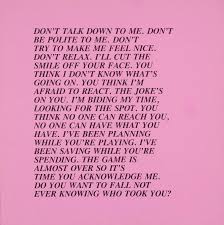

Jenny Holzer in The Social Media Age

Josie Thaddeus-Johns at The Baffler:

IN 1997, when Jenny Holzer created Installation for Bilbao for the Spanish city’s newly opened Guggenheim, social media did not exist. Google had yet to be founded; dial-up internet meant listening to an inhuman caterwaul every time you connected; and when a webpage included a large image, one line of pixels arrived at a time, like tweets on a moving feed.

IN 1997, when Jenny Holzer created Installation for Bilbao for the Spanish city’s newly opened Guggenheim, social media did not exist. Google had yet to be founded; dial-up internet meant listening to an inhuman caterwaul every time you connected; and when a webpage included a large image, one line of pixels arrived at a time, like tweets on a moving feed.

Twenty-two years later, the minimalist artist has returned to the Frank Gehry-designed museum with an extensive collection of new and archival works. Though “Thing Indescribable” is not quite a retrospective, the show covers her entire career, beginning with the series Truisms, a now-iconic set of phrases that she wrote between 1977 and 1979. Originally pasted up in public spaces around New York, they later made their way onto benches, electronic signs, and T-shirts, turning her words into public sculptures.

more here.

Remembering Michael Rabin

Sudip Bose at The American Scholar:

He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.”

He was, to be sure, one of those candles that burn twice as bright but half as long, an all-American violinist in an age dominated by the European virtuoso. He was born on this date in 1936, into a highly musical Manhattan family, his father a violinist in the New York Philharmonic, his mother a piano teacher who had studied at Juilliard. At the age of three, Rabin demonstrated perfect pitch, and soon he was taking piano lessons with his mother, a larger-than-life figure whose Olympian standards were exceeded only by her work ethic and drive. Anthony Feinstein writes in his biography of the violinist that the “force of her character demanded obedience and gratitude. She was unable to brook dissent, and displayed a ruthlessness when it came to enforcing her will.” She had lost her first son, who had shown great promise as a pianist, to scarlet fever, and perhaps because of this, she was all the more determined to make something of her younger son’s talent. Her demands, Feinstein writes, were clear: “the relentless pursuit of excellence, the drive for perfection, the expectation of long, exhausting hours dedicated to practicing music.”

more here.

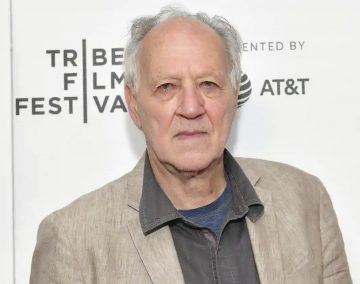

Werner Herzog: ‘I’m not a pundit. Don’t push me into that corner’

Charles Bramesco in The Guardian:

Director-documentarian-deity Werner Herzog has stared death in the face, blazed a path through madness, and charted the outermost limits of human experience. For a man of such stature, sitting down with one of the most significant public figures of the twentieth century was no biggie.

Director-documentarian-deity Werner Herzog has stared death in the face, blazed a path through madness, and charted the outermost limits of human experience. For a man of such stature, sitting down with one of the most significant public figures of the twentieth century was no biggie.

“We had an instant rapport,” Herzog says of his recent rendezvous with Mikhail Gorbachev, in an interview with the Guardian during the Tribeca film festival. His new non-fiction feature Meeting Gorbachev chronicles three tête-à-têtes across the span of six months between the film-maker and the final general secretary of the Communist party of the Soviet Union, in which two personalities known for exuding an intense presence immediately took a shine to one another.

“We have similar backgrounds,” Herzog explains, “growing up after the war and knowing what it means to be hungry, having traveled very extensively, living in a very remote area without even running water, a devastated landscape. We knew of one another. Apparently, Gorbachev had seen some of my films and done a lot of homework on me. He had a huge stack of remarks about my work … We brought him chocolates without sugar from a London chocolatier.”

More here.

In the story of democracy: are we at the beginning, in the middle or near the end?

More here. [Thanks to Misha Lepetic.]

Nils Lonberg: The entrepreneur behind the cancer immunotherapy revolution

Matthew Herper in Stat:

Nils Lonberg, a scientist at the center of a revolution in cancer therapy, has had a career full of fateful decisions. One of the most crucial: buying an entire bottle of whiskey at a hotel bar.

Nils Lonberg, a scientist at the center of a revolution in cancer therapy, has had a career full of fateful decisions. One of the most crucial: buying an entire bottle of whiskey at a hotel bar.

It was 1998. Lonberg had just been part of a group dinner with Jim Allison, the charismatic, harmonica-playing scientist who would go on to win a Nobel Prize. After the meal, Lonberg took Allison aside and invited him to have a drink; they stayed up drinking, and talking, until the wee small hours of the morning.

Allison had been trying to find a company to turn his discoveries into life-changing medicines. Lonberg, at the time an executive at a small company, wanted to be the one to make it happen.

More here.