John Horgan in Scientific American:

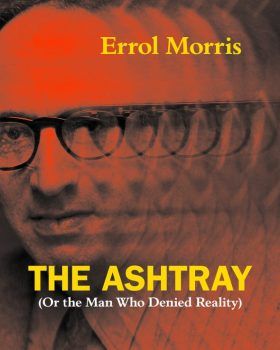

In 1972 Thomas Kuhn hurled an ashtray at Errol Morris. Already renowned for The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, published a decade earlier, Kuhn was at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and Morris was his graduate student in history and philosophy of science. During a meeting in Kuhn’s office, Morris questioned Kuhn’s views on paradigms, the webs of conscious and unconscious assumptions that underpin, say, Aristotle’s, Newton’s or Einstein’s physics. You cannot say one paradigm is truer than another, according to Kuhn, because there is no objective standard by which to judge them. Paradigms are incomparable, or “incommensurable.” If that were true, Morris asked, wouldn’t history of science be impossible? Wouldn’t the past be inaccessible–except, Morris added, for “someone who imagines himself to be God?” Kuhn realized his student had just insulted him. He muttered, “He’s trying to kill me. He’s trying to kill me.” Then he threw the ashtray at Morris and threw him out of the program.

In 1972 Thomas Kuhn hurled an ashtray at Errol Morris. Already renowned for The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, published a decade earlier, Kuhn was at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and Morris was his graduate student in history and philosophy of science. During a meeting in Kuhn’s office, Morris questioned Kuhn’s views on paradigms, the webs of conscious and unconscious assumptions that underpin, say, Aristotle’s, Newton’s or Einstein’s physics. You cannot say one paradigm is truer than another, according to Kuhn, because there is no objective standard by which to judge them. Paradigms are incomparable, or “incommensurable.” If that were true, Morris asked, wouldn’t history of science be impossible? Wouldn’t the past be inaccessible–except, Morris added, for “someone who imagines himself to be God?” Kuhn realized his student had just insulted him. He muttered, “He’s trying to kill me. He’s trying to kill me.” Then he threw the ashtray at Morris and threw him out of the program.

Morris went on to become an acclaimed maker of documentaries. He won an Academy Award for The Fog of War, his portrait of “war criminal”—Morris’s term—Robert McNamara. His documentary The Thin Blue Line helped overturn the conviction of a man on death row for murder. Morris never forgave Kuhn, who was, in Morris’s eyes, a bad person and bad philosopher. In his book The Ashtray (Or the Man Who Denied Reality), Morris attacks the cult—my term, but I suspect Morris would approve, since it describes a group bound by irrational allegiance to a domineering leader–of Kuhn. “Many may see this book as a vendetta,” Morris writes. “Indeed it is.” Morris blames Kuhn for undermining the notion that there is a real world out there, which we can, with some effort, come to know. Morris wants to rebut this skeptical assertion, which he believes has insidious effects. The denial of objective truth enables totalitarianism and genocide and “ultimately, perhaps irrevocably, undermines civilization.”

More here.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Lawrence Ferlinghetti Consciousness has many aspects, from experience to wakefulness to self-awareness. One aspect is imagination: our minds can conjure up multiple hypothetical futures to help us decide which choices we should make. Where did that ability come from? Today’s guest, Malcolm MacIver, pinpoints an important transition in the evolution of consciousness to when fish first climbed on to land, and could suddenly see much farther, which in turn made it advantageous to plan further in advance. If this idea is true, it might help us understand some of the abilities and limitations of our cognitive capacities, with potentially important ramifications for our future as a species.

Consciousness has many aspects, from experience to wakefulness to self-awareness. One aspect is imagination: our minds can conjure up multiple hypothetical futures to help us decide which choices we should make. Where did that ability come from? Today’s guest, Malcolm MacIver, pinpoints an important transition in the evolution of consciousness to when fish first climbed on to land, and could suddenly see much farther, which in turn made it advantageous to plan further in advance. If this idea is true, it might help us understand some of the abilities and limitations of our cognitive capacities, with potentially important ramifications for our future as a species. Over the weekend, the Times tried to soften the emotional blow for the millions of Americans trained in these years to place hopes for the overturn of the Trump presidency in Mueller. As with most press coverage, there was little pretense that the Mueller probe was supposed to be a neutral fact-finding mission, as apposed to religious allegory, with Mueller cast as the hero sent to slay the monster.

Over the weekend, the Times tried to soften the emotional blow for the millions of Americans trained in these years to place hopes for the overturn of the Trump presidency in Mueller. As with most press coverage, there was little pretense that the Mueller probe was supposed to be a neutral fact-finding mission, as apposed to religious allegory, with Mueller cast as the hero sent to slay the monster. A wooden box containing one of the most valuable books in the world arrives in Los Angeles on October 14, 1950, with little more fanfare—or security—than a Sears catalog. Code-named “the commode,” it was flown from London via regular parcel post, and while it is being delivered locally by Tice and Lynch, a high-end customs broker and shipping company, its agents have no idea what they are carrying and take no special precautions.

A wooden box containing one of the most valuable books in the world arrives in Los Angeles on October 14, 1950, with little more fanfare—or security—than a Sears catalog. Code-named “the commode,” it was flown from London via regular parcel post, and while it is being delivered locally by Tice and Lynch, a high-end customs broker and shipping company, its agents have no idea what they are carrying and take no special precautions.

There are a handful of niche artists whom I love to play for friends who have never heard them before. Music critics are infamous for these sorts of overbearing displays—smugly dropping a needle to a record and then staring, expectantly. It’s awful! Yet the first time that a person hears the singer Scott Walker—who died on Friday, in London, at the age of seventy-six—a palpable transformation occurs, and it’s extraordinary to witness. At first,

There are a handful of niche artists whom I love to play for friends who have never heard them before. Music critics are infamous for these sorts of overbearing displays—smugly dropping a needle to a record and then staring, expectantly. It’s awful! Yet the first time that a person hears the singer Scott Walker—who died on Friday, in London, at the age of seventy-six—a palpable transformation occurs, and it’s extraordinary to witness. At first,  As a child growing up in the Netherlands, Hanna ten Brink spent many days lingering by a pond in her family’s garden, fascinated by metamorphosis. Tadpoles hatched from eggs in the pond and swam about, sucking tiny particles of food into their mouths. After a few weeks, the tadpoles lost their tails, sprouted legs and hopped onto land, where they could catch insects with their new tongues. Eventually Dr. ten Brink became an evolutionary biologist. Now science has brought her back to that childhood fascination. Eighty percent of all animal species experience metamorphosis — from frogs to flatfish to butterflies to jellyfish. Scientists are deeply puzzled as to how it became so common.

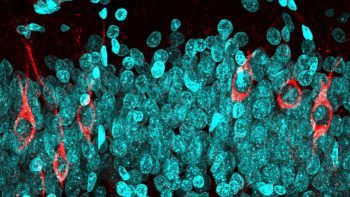

As a child growing up in the Netherlands, Hanna ten Brink spent many days lingering by a pond in her family’s garden, fascinated by metamorphosis. Tadpoles hatched from eggs in the pond and swam about, sucking tiny particles of food into their mouths. After a few weeks, the tadpoles lost their tails, sprouted legs and hopped onto land, where they could catch insects with their new tongues. Eventually Dr. ten Brink became an evolutionary biologist. Now science has brought her back to that childhood fascination. Eighty percent of all animal species experience metamorphosis — from frogs to flatfish to butterflies to jellyfish. Scientists are deeply puzzled as to how it became so common. One of the thorniest debates in neuroscience is whether people can make new neurons after their brains stop developing in adolescence—a process known as neurogenesis. Now, a new study finds that even people long past middle age can make fresh brain cells, and that past studies that failed to spot these newcomers may have used flawed methods. The work “provides clear, definitive evidence that neurogenesis persists throughout life,” says Paul Frankland, a neuroscientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. “For me, this puts the issue to bed.” Researchers have long hoped that neurogenesis could help treat brain disorders like depression and Alzheimer’s disease. But last year, a study in Nature reported that

One of the thorniest debates in neuroscience is whether people can make new neurons after their brains stop developing in adolescence—a process known as neurogenesis. Now, a new study finds that even people long past middle age can make fresh brain cells, and that past studies that failed to spot these newcomers may have used flawed methods. The work “provides clear, definitive evidence that neurogenesis persists throughout life,” says Paul Frankland, a neuroscientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. “For me, this puts the issue to bed.” Researchers have long hoped that neurogenesis could help treat brain disorders like depression and Alzheimer’s disease. But last year, a study in Nature reported that

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

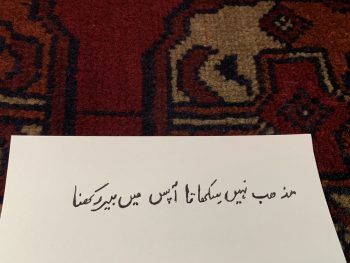

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.