Steve Donoghue in The Christian Science Monitor:

James Crabtree’s The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age devotes the bulk of its length to the new cadre of super-rich that has arisen in India’s newly resurgent economy, but it opens with an important point: India is still an intensely poor country. The average citizen earns less than $2,000 a year, and the low-end of what constitutes the richest one percent of the country is only around $33,000. The richest one percent of the country owns more than half the nation’s wealth; it’s a starker income disparity than virtually any other country on Earth.

James Crabtree’s The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age devotes the bulk of its length to the new cadre of super-rich that has arisen in India’s newly resurgent economy, but it opens with an important point: India is still an intensely poor country. The average citizen earns less than $2,000 a year, and the low-end of what constitutes the richest one percent of the country is only around $33,000. The richest one percent of the country owns more than half the nation’s wealth; it’s a starker income disparity than virtually any other country on Earth.

As in most such cases, the income gap is braced and fueled by immense wide-scale graft, and readers at the outset of Crabtree’s book are left with no illusions about the state of the economy underlying this new oligarchy of super-wealth. “There is every reason to believe that, without intervention, the gap between India’s rich and the rest will keep widening,” Crabtree writes, pointing in every chapter to the symbiotic link between unregulated mega-wealth and rampant corruption. The balance between these two forces is the thematic balance of the entire book, and according to the author, it “lies at the heart of the struggles of India’s industrial economy.”

In fast-paced evocative prose, Crabtree, a professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore and a former Mumbai bureau chief for the Financial Times, describes some of the foremost players in that continuous struggle at the heart of India’s booming but troubled economy. For good or ill, the billionaires are the stars of this show – colorful, conflicted figures like “onetime billionaire brewer and airline magnate” Vijay Mallya, the self-dubbed “King of Good Times” who at his peak of power and infamy, “was ringmaster of his own circus: a bon vivant and hard drinker; a man of coteries and Gatsby-style parties and famously ill-disciplined timekeeping.” Mallya had once been India’s richest man, until forced into exile by corruption scandals.

More here.

In his new book, In Defense of Public Lands: The Case against Privatization and Transfer (Temple University Press), Steven Davis, political science professor at Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin, takes on the “privatizers.” His book is an even-handed and thorough look at public lands in the United States. Although public support for wilderness, national parks, and other public lands

In his new book, In Defense of Public Lands: The Case against Privatization and Transfer (Temple University Press), Steven Davis, political science professor at Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin, takes on the “privatizers.” His book is an even-handed and thorough look at public lands in the United States. Although public support for wilderness, national parks, and other public lands  Cordelia Fine in the Financial Times:

Cordelia Fine in the Financial Times: Richard V Reeves at Aeon:

Richard V Reeves at Aeon: Eric Levitz in NY Magazine [h/t: Leonard Benardo]:

Eric Levitz in NY Magazine [h/t: Leonard Benardo]: A common argument against Bergman is that he is fated for oblivion because his movies did not advance the art of film; they were

A common argument against Bergman is that he is fated for oblivion because his movies did not advance the art of film; they were

It’s hard to imagine, at this distance, how it must have been to be Aristotle in his own time: cutting-edge rather than foundational. We see him standing at the beginning of western philosophy and surveying something like virgin territory. Did it feel like that at the time? He didn’t know, obviously, that he was an Ancient – at the start of things, as we now see it, rather than, say, at their end. He was interdisciplinary before there were really disciplines to worry about. Look at him, romping across the territory of possible human knowledge like a big dog snapping at butterflies, or

It’s hard to imagine, at this distance, how it must have been to be Aristotle in his own time: cutting-edge rather than foundational. We see him standing at the beginning of western philosophy and surveying something like virgin territory. Did it feel like that at the time? He didn’t know, obviously, that he was an Ancient – at the start of things, as we now see it, rather than, say, at their end. He was interdisciplinary before there were really disciplines to worry about. Look at him, romping across the territory of possible human knowledge like a big dog snapping at butterflies, or  Lindsey Abel takes an anaesthetized mouse from a plastic container and lays it on the lab bench. With a syringe, she injects a slurry of pink cancer cells under the skin of the animal’s right flank. These cells once belonged to a person with tongue cancer, a former smoker whose disease recurred despite radiation and surgery. The mouse is the second rodent to harbour them, creating a model for cancer known as a patient-derived xenograft (PDX). The tumour that grows inside will provide cells that can be transferred to more mice. Abel has performed this procedure hundreds of time since she joined Randall Kimple’s lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Kimple, a radiation oncologist, uses PDX mice to carry out experiments on human tumours that would be impractical in people, such as testing new drugs and identifying factors that predict a good response to treatment. His lab has created more than 50 PDX mice since 2011. Kimple’s lab is not the only one doing this; PDX mice have exploded in popularity over the past decade and are beginning to supplant other techniques for modelling cancer in research and drug development, such as mice implanted with cancer cell lines. Because the models use fresh human tumour fragments rather than cells grown in a Petri dish, researchers have long hoped that PDXs would model tumour behaviour more accurately, and perhaps

Lindsey Abel takes an anaesthetized mouse from a plastic container and lays it on the lab bench. With a syringe, she injects a slurry of pink cancer cells under the skin of the animal’s right flank. These cells once belonged to a person with tongue cancer, a former smoker whose disease recurred despite radiation and surgery. The mouse is the second rodent to harbour them, creating a model for cancer known as a patient-derived xenograft (PDX). The tumour that grows inside will provide cells that can be transferred to more mice. Abel has performed this procedure hundreds of time since she joined Randall Kimple’s lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Kimple, a radiation oncologist, uses PDX mice to carry out experiments on human tumours that would be impractical in people, such as testing new drugs and identifying factors that predict a good response to treatment. His lab has created more than 50 PDX mice since 2011. Kimple’s lab is not the only one doing this; PDX mice have exploded in popularity over the past decade and are beginning to supplant other techniques for modelling cancer in research and drug development, such as mice implanted with cancer cell lines. Because the models use fresh human tumour fragments rather than cells grown in a Petri dish, researchers have long hoped that PDXs would model tumour behaviour more accurately, and perhaps

When the European Union slapped Google with a $5 billion antitrust fine recently, President Trump readied his exclamation points,

When the European Union slapped Google with a $5 billion antitrust fine recently, President Trump readied his exclamation points,  Lenore Palladino in Boston Review:

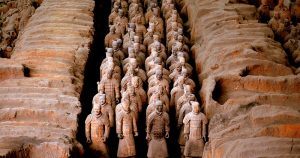

Lenore Palladino in Boston Review: In fact, the entire story of the Emperor and his Mausoleum is one of history, mystery, and discovery. History: the chronicles and annals of Chinese history help us to outline the straightforward historical record: this provides the basic starting point of the story. Mystery: since the emperor’s death there have been several mysteries, including the character of the emperor himself, the deliberately disguised location of the tomb, its real purpose and more recently the uncertain role of the terracotta warriors. Discovery: in the past this was serendipitous, as in the 1974 discovery of the warriors, but today it has become systematic and adopts advanced archaeological and scientific techniques which fill out the history and build on the mystery.

In fact, the entire story of the Emperor and his Mausoleum is one of history, mystery, and discovery. History: the chronicles and annals of Chinese history help us to outline the straightforward historical record: this provides the basic starting point of the story. Mystery: since the emperor’s death there have been several mysteries, including the character of the emperor himself, the deliberately disguised location of the tomb, its real purpose and more recently the uncertain role of the terracotta warriors. Discovery: in the past this was serendipitous, as in the 1974 discovery of the warriors, but today it has become systematic and adopts advanced archaeological and scientific techniques which fill out the history and build on the mystery.

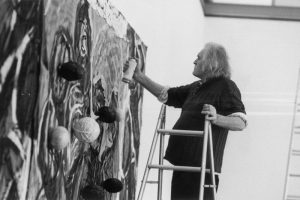

Mario Merz, a leading figure of the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera, first began to draw in prison, after being arrested in 1945 for his involvement with an anti-Facist group in Turin. He recorded his cell mate’s beard in continuous spirals, often without lifting his pencil off the paper. After his release, he painted leaves, animals and biomorphic shapes in a colourful Expressionist style. It wasn’t until the 1960s, though, that he began creating the three-dimensional works – using everyday objects and materials, such as wood, wool, glass, fruit, umbrellas and newspaper – for which he became famous.

Mario Merz, a leading figure of the Italian avant-garde movement Arte Povera, first began to draw in prison, after being arrested in 1945 for his involvement with an anti-Facist group in Turin. He recorded his cell mate’s beard in continuous spirals, often without lifting his pencil off the paper. After his release, he painted leaves, animals and biomorphic shapes in a colourful Expressionist style. It wasn’t until the 1960s, though, that he began creating the three-dimensional works – using everyday objects and materials, such as wood, wool, glass, fruit, umbrellas and newspaper – for which he became famous.