Amanda Moniz in Smithsonian:

The arts are “a space where we can give dignity to others while interrogating our own circumstances,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s annual symposium, The Power of Giving: Philanthropy’s Impact on American Life. Held this spring, the program explored philanthropy’s impact on and through culture and the arts. As he reflected on the relationship between giving and the arts, Walker said that “throughout our history, we have seen artists and activists work hand in hand. We have seen art inspire and elevate whole movements for change.” As Walker suggests, music, storytelling, drama, and other arts have an emotional impact that motivates giving time and money to causes, while philanthropic appeals help artists attract audiences. To continue the conversation about the arts and giving, here’s a look at three objects that tell stories about how Americans used the arts to promote social change in the 1800s.

The arts are “a space where we can give dignity to others while interrogating our own circumstances,” said Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s annual symposium, The Power of Giving: Philanthropy’s Impact on American Life. Held this spring, the program explored philanthropy’s impact on and through culture and the arts. As he reflected on the relationship between giving and the arts, Walker said that “throughout our history, we have seen artists and activists work hand in hand. We have seen art inspire and elevate whole movements for change.” As Walker suggests, music, storytelling, drama, and other arts have an emotional impact that motivates giving time and money to causes, while philanthropic appeals help artists attract audiences. To continue the conversation about the arts and giving, here’s a look at three objects that tell stories about how Americans used the arts to promote social change in the 1800s.

In the 1840s, the popular Hutchinson Family Singers from New Hampshire introduced music to the developing antislavery movement. As the sheet music for “The Grave of Bonaparte” suggests, the singers were concerned about freedom in other forms and many places, but they had their biggest impact on the American antislavery movement. Performing before integrated audiences, siblings Judson, John, Asa, and Abby—who were managed by their brother Jesse—helped nurture opposition to slavery among those not exposed to its evils. They also helped build far-flung antislavery networks thanks to their travel and the newspaper coverage of their events. Moreover, the success of their antislavery songs showed that the cause had commercial appeal. Works such as the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin would cater to that appeal–and help further develop antislavery sentiment. In addition to their contributions to reform causes, the group shaped American musical identity. At a time when Americans favored European musicians, the Hutchinson Family Singers spurred new interest in American music.

More here.

After I came back from Australia, I wondered about a large bauxite mine that I’d heard of, where termites had rehabilitated the land. I wondered if there was more to the story than the fact that they fertilized the soil and recycled the grasses. There seemed to be a gap between bugs dropping a few extra nitrogen molecules in their poo and the creation of a whole forest. What were they doing down there? I started going through my files, looking for people working on landscapes. This led me to the work of a mathematician named Corina Tarnita and an ecologist named Rob Pringle. When I contacted her, Corina had just moved to Princeton from Harvard and, with Rob, had set about using mathematical modeling to figure out what termites were doing in dry landscapes in Kenya. As it happened, I had interviewed Rob back in 2010, when he and a team published a paper on the role of termites in the African savanna ecosystems that are home to elephants and giraffes.

After I came back from Australia, I wondered about a large bauxite mine that I’d heard of, where termites had rehabilitated the land. I wondered if there was more to the story than the fact that they fertilized the soil and recycled the grasses. There seemed to be a gap between bugs dropping a few extra nitrogen molecules in their poo and the creation of a whole forest. What were they doing down there? I started going through my files, looking for people working on landscapes. This led me to the work of a mathematician named Corina Tarnita and an ecologist named Rob Pringle. When I contacted her, Corina had just moved to Princeton from Harvard and, with Rob, had set about using mathematical modeling to figure out what termites were doing in dry landscapes in Kenya. As it happened, I had interviewed Rob back in 2010, when he and a team published a paper on the role of termites in the African savanna ecosystems that are home to elephants and giraffes. What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my

What you see below are images from my notebooks, recently posted on my  IN HIS ARTICLE

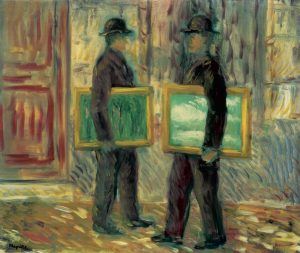

IN HIS ARTICLE It is sometimes said that Surrealist paintings are disappointing up close; perhaps we see them so often in reproduction that by the time we see the real ones in a museum they’ve lost some of their strangeness. René Magritte’s paintings could fall into that trap. His bowler hats, apples, puffy clouds and pipes have popped up on coffee mugs, tote bags and dorm-room posters for decades. Not to mention album covers: Jeff Beck used Magritte’s “The Listening Room” on the cover of his 1969 LP “Beck-Ola”. Is Magritte too ubiquitous to be uncanny? No, is the takeaway from “The Fifth Season”, an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Displaying lesser-known work alongside some of his best-loved paintings, it shows that Magritte still has the power to surprise.

It is sometimes said that Surrealist paintings are disappointing up close; perhaps we see them so often in reproduction that by the time we see the real ones in a museum they’ve lost some of their strangeness. René Magritte’s paintings could fall into that trap. His bowler hats, apples, puffy clouds and pipes have popped up on coffee mugs, tote bags and dorm-room posters for decades. Not to mention album covers: Jeff Beck used Magritte’s “The Listening Room” on the cover of his 1969 LP “Beck-Ola”. Is Magritte too ubiquitous to be uncanny? No, is the takeaway from “The Fifth Season”, an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Displaying lesser-known work alongside some of his best-loved paintings, it shows that Magritte still has the power to surprise. In July 3, 2014, Misty Mayo boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Los Angeles. Desperate to escape her hometown of Modesto in Stanislaus County, 300 miles north in California’s Central Valley, the 41-year-old thought the 4th of July fireworks in LA would be the perfect antidote. Even a mugging at the Modesto bus station didn’t deter her. When she arrived in LA the next morning with just a few dollars in her pocket, Misty immediately asked a police officer for directions to the fireworks display. She also knew she would need to find a Target pharmacy to refill her medication, but decided it could wait until later.

In July 3, 2014, Misty Mayo boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Los Angeles. Desperate to escape her hometown of Modesto in Stanislaus County, 300 miles north in California’s Central Valley, the 41-year-old thought the 4th of July fireworks in LA would be the perfect antidote. Even a mugging at the Modesto bus station didn’t deter her. When she arrived in LA the next morning with just a few dollars in her pocket, Misty immediately asked a police officer for directions to the fireworks display. She also knew she would need to find a Target pharmacy to refill her medication, but decided it could wait until later. You are now a highly successful public intellectual. In what ways has international recognition changed you?

You are now a highly successful public intellectual. In what ways has international recognition changed you? Aerial and satellite images of the colony living on the remote subantarctic island of Île aux Cochons, in the southern Indian Ocean, suggests the number of penguins has fallen from around 500,000 pairs in the 1980s, to just 60,000 pairs in photographs taken in 2015 and 2017.

Aerial and satellite images of the colony living on the remote subantarctic island of Île aux Cochons, in the southern Indian Ocean, suggests the number of penguins has fallen from around 500,000 pairs in the 1980s, to just 60,000 pairs in photographs taken in 2015 and 2017. We get the word “mesmerize” from a doctor named Franz Anton Mesmer, who in Paris in the late 18th century posited the existence of an invisible natural force connecting all living things — a force you could manipulate to physically affect another person.

We get the word “mesmerize” from a doctor named Franz Anton Mesmer, who in Paris in the late 18th century posited the existence of an invisible natural force connecting all living things — a force you could manipulate to physically affect another person. For anyone who has ever kept a diary, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness(first published in the US in 2015) will give pause for thought. The American writer kept a diary over 25 years and it was 800,000 words long. She elects not to publish a word of it in Ongoingness. It turns out she does not wish to look back at what she wrote. This absorbing book – brief as a breath – examines the need to record. It seems, even if she never spells it out, that writing the diary was a compulsive rebuffing of mortality. Like all diarists, she was trying to commandeer time. A diary gives the writer the illusion of stopping time in its tracks. And time – making her peace with its ongoingness – is Manguso’s obsession. Her book hints at diary-keeping as neurosis, a hoarding that is almost a syndrome, a malfunction, a grief at having no way to halt loss.

For anyone who has ever kept a diary, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness(first published in the US in 2015) will give pause for thought. The American writer kept a diary over 25 years and it was 800,000 words long. She elects not to publish a word of it in Ongoingness. It turns out she does not wish to look back at what she wrote. This absorbing book – brief as a breath – examines the need to record. It seems, even if she never spells it out, that writing the diary was a compulsive rebuffing of mortality. Like all diarists, she was trying to commandeer time. A diary gives the writer the illusion of stopping time in its tracks. And time – making her peace with its ongoingness – is Manguso’s obsession. Her book hints at diary-keeping as neurosis, a hoarding that is almost a syndrome, a malfunction, a grief at having no way to halt loss. When she moved from Michigan to be near her daughter in Cary, N.C., Bernadine Lewandowski insisted on renting an apartment five minutes away. Her daughter, Dona Jones, would have welcomed her mother into her own home, but “she’s always been very independent,” Ms. Jones said. Like most people in their 80s, Ms. Lewandowski contended with several chronic illnesses and took medication for osteoporosis, heart failure and pulmonary disease. Increasingly forgetful, she had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. She used a cane for support as she walked around her apartment complex. Still, “she was trucking along just fine,” said her geriatrician, Dr. Maureen Dale. “Minor health issues here and there, but she was taking good care of herself.” But last September, Ms. Lewandowski entered a hospital after a compression fracture of her vertebra caused pain too intense to be managed at home. Over four days, she used nasal oxygen to help her breathe and received intravenous morphine for pain relief, later graduating to oxycodone tablets. Even after her discharge, the stress and disruptions of hospitalization — interrupted sleep, weight loss, mild delirium, deconditioning caused by days in bed — left her disoriented and weakened, a vulnerable state some researchers call “

When she moved from Michigan to be near her daughter in Cary, N.C., Bernadine Lewandowski insisted on renting an apartment five minutes away. Her daughter, Dona Jones, would have welcomed her mother into her own home, but “she’s always been very independent,” Ms. Jones said. Like most people in their 80s, Ms. Lewandowski contended with several chronic illnesses and took medication for osteoporosis, heart failure and pulmonary disease. Increasingly forgetful, she had been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. She used a cane for support as she walked around her apartment complex. Still, “she was trucking along just fine,” said her geriatrician, Dr. Maureen Dale. “Minor health issues here and there, but she was taking good care of herself.” But last September, Ms. Lewandowski entered a hospital after a compression fracture of her vertebra caused pain too intense to be managed at home. Over four days, she used nasal oxygen to help her breathe and received intravenous morphine for pain relief, later graduating to oxycodone tablets. Even after her discharge, the stress and disruptions of hospitalization — interrupted sleep, weight loss, mild delirium, deconditioning caused by days in bed — left her disoriented and weakened, a vulnerable state some researchers call “ The ill-defined term ‘populism’ is used in different senses not just by common people or the media, but even among social scientists. Economists usually interpret it as short-termism at the expense of the long-term health of the economy. They usually refer to it in describing macro-economic profligacy, leading to galloping budget deficits in pandering to all kinds of pressure groups for larger government spending and to the consequent inflation—examples abound in the recent history of Latin America (currently in virulent display in Venezuela). Political scientists, on the other hand, refer to the term in the context of a certain widespread distrust in the institutions of representative democracy, when people look for a strong leader who can directly embody the ‘popular will’ and cut through the tardy processes of the rule of law and encumbrances like basic human rights or minority rights. Even though I am an economist, in this article I shall mainly confine myself to the latter use of the term.

The ill-defined term ‘populism’ is used in different senses not just by common people or the media, but even among social scientists. Economists usually interpret it as short-termism at the expense of the long-term health of the economy. They usually refer to it in describing macro-economic profligacy, leading to galloping budget deficits in pandering to all kinds of pressure groups for larger government spending and to the consequent inflation—examples abound in the recent history of Latin America (currently in virulent display in Venezuela). Political scientists, on the other hand, refer to the term in the context of a certain widespread distrust in the institutions of representative democracy, when people look for a strong leader who can directly embody the ‘popular will’ and cut through the tardy processes of the rule of law and encumbrances like basic human rights or minority rights. Even though I am an economist, in this article I shall mainly confine myself to the latter use of the term. When Mrs. William Shakespeare died on this August day in 1623, her family and friends believed they would lay her to eternal rest beside her renowned husband. They did not. They did inter an ordinary wife and mother, but the memory of her went out to become a Frankenstein monster, cut up and reassembled down the centuries. Few of the many makeovers done to Anne Hathaway Shakespeare since her passing have been flattering.

When Mrs. William Shakespeare died on this August day in 1623, her family and friends believed they would lay her to eternal rest beside her renowned husband. They did not. They did inter an ordinary wife and mother, but the memory of her went out to become a Frankenstein monster, cut up and reassembled down the centuries. Few of the many makeovers done to Anne Hathaway Shakespeare since her passing have been flattering.

I’m tempted to describe Marion Milner’s book A Life of One’s Own as the missing manual for owners of a human mind. However, it’s not didactic or prescriptive. In fact, it’s useful mainly because it’s nothing like a manual or a self-help book. The book is more like an insightful travelogue by an articulate and honest observer with a gift for using vivid physical imagery and metaphors to describe her inner world.

I’m tempted to describe Marion Milner’s book A Life of One’s Own as the missing manual for owners of a human mind. However, it’s not didactic or prescriptive. In fact, it’s useful mainly because it’s nothing like a manual or a self-help book. The book is more like an insightful travelogue by an articulate and honest observer with a gift for using vivid physical imagery and metaphors to describe her inner world.