by Jeroen Bouterse

Steven Pinker’s 2018 book Enlightenment Now is a reasoned defense of the values of the Enlightenment: of reason, science, humanism and progress. Pinker uses most of his space to demonstrate, positively, how the attitudes and institutions associated with Enlightenment thought have done good in the world. However, he has also woven through his book a clear motif of defense against ‘counter-Enlightenments’: the opponents of Enlightenment values.

These opponents are, among others, religious faith and some radical kinds of environmentalism. The anti-Enlightenment sentiments that Pinker deals with most extensively, however, are those of the so-called ‘Second Culture’: “the world-view of many literary intellectuals and cultural critics”, who have been criticizing the Enlightenment specifically for its devotion to the sciences. Pinker devotes an entire chapter to this Second Culture and its “high-brow war on science” (mostly overlapping with this article in The Chronicle of Higher Education). Treatment of science in liberal-arts curricula is

“pernicious […]. Students can graduate with only a trifling exposure to science, and what they do learn is often designed to poison them against it.” (395)

Pinker complains that science gets blamed for all kinds of crimes, such as 19th-century racism – which, if anything, is “the brainchild not of science but of the humanities” (398). Also, students are made to read Thomas Kuhn. Kuhn famously coined the notion of ‘paradigms’ in order to make the case that the assessment of progress in science depends on a shared set of assumptions. This way of thinking leads to the cynical conclusion that science does not converge upon the truth at all, says Pinker.

Intellectually, this is far from the best part of Enlightenment Now: Pinker’s definition of the other side is imprecise, his supporting data uncharacteristically anecdotal and one-sided. (Kuhn had a PhD in physics, and it is hard to find in his work any hostile remarks about science.) The reason Pinker can get away with this is that he seems to be stating the obvious: the existence of a divide between the sciences and the humanities that is not institutional but cultural has been accepted wisdom in Western culture for decades. Read more »

The 2020s will have a name. In the nursing homes of the future, Millennials’ grandchildren will hear all about the coming decade. Gran will remove her headset, loaded out with VR-entertainment and the latest in biometric tech, and she’ll tell the kids about the world as it was in the third decade of the 21st Century. For now, we look ahead to the Twenties, a decade certain to be charged with meaning, roaring in one way or another.

The 2020s will have a name. In the nursing homes of the future, Millennials’ grandchildren will hear all about the coming decade. Gran will remove her headset, loaded out with VR-entertainment and the latest in biometric tech, and she’ll tell the kids about the world as it was in the third decade of the 21st Century. For now, we look ahead to the Twenties, a decade certain to be charged with meaning, roaring in one way or another. One of my favorite quotes about artificial intelligence is often attributed to pioneering computer scientists Hans Moravec and Marvin Minsky. To paraphrase: “The most important thing we have learned from three decades of AI research is that the hard things are easy and the easy things are hard”. In other words, we have been hoodwinked for a long time. We thought that vision and locomotion and housework would be easy and language recognition and chess and driving would be hard. And yet it has turned out that we have made significant strides in tackling the latter while hardly making a dent in the former. The lower-level skills seem to require significantly more understanding and computational power than seemingly more sophisticated, higher-level skills.

One of my favorite quotes about artificial intelligence is often attributed to pioneering computer scientists Hans Moravec and Marvin Minsky. To paraphrase: “The most important thing we have learned from three decades of AI research is that the hard things are easy and the easy things are hard”. In other words, we have been hoodwinked for a long time. We thought that vision and locomotion and housework would be easy and language recognition and chess and driving would be hard. And yet it has turned out that we have made significant strides in tackling the latter while hardly making a dent in the former. The lower-level skills seem to require significantly more understanding and computational power than seemingly more sophisticated, higher-level skills.

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked.

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked. This weekend, the New York Times’ print subscribers received something kind of crazy: A 66-page magazine with only a single article — and it’s on climate change. The long-form piece, written by Nathaniel Rich and titled “Losing Earth,”

This weekend, the New York Times’ print subscribers received something kind of crazy: A 66-page magazine with only a single article — and it’s on climate change. The long-form piece, written by Nathaniel Rich and titled “Losing Earth,”

Charlotte Higgins

Charlotte Higgins On a cool spring day in April 2014, Dayne Walling, the mayor of Flint, Mich., entered an old water-treatment plant and, amid cheers from a crowd of city officials and engineers, pushed a small black button on a cinder-block wall. With that gesture, the mayor switched Flint’s water supply from a tested and reliable source provided by the city of Detroit to a cheaper and untested one, the nearby Flint River. City officials defended the move as necessary cost-cutting for a bankrupt city. Like his colleagues, Walling — a Rhodes scholar who had a master’s degree in urban studies — believed that Flint, by deciding to rely on its own river for water, was taking control of its destiny. He called it “a historic moment.”

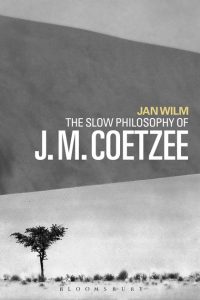

On a cool spring day in April 2014, Dayne Walling, the mayor of Flint, Mich., entered an old water-treatment plant and, amid cheers from a crowd of city officials and engineers, pushed a small black button on a cinder-block wall. With that gesture, the mayor switched Flint’s water supply from a tested and reliable source provided by the city of Detroit to a cheaper and untested one, the nearby Flint River. City officials defended the move as necessary cost-cutting for a bankrupt city. Like his colleagues, Walling — a Rhodes scholar who had a master’s degree in urban studies — believed that Flint, by deciding to rely on its own river for water, was taking control of its destiny. He called it “a historic moment.” Particularly since the publication of Elizabeth Costello (2003), a strong academic conversation on literature and philosophy has developed around the writings of J.M. Coetzee. As literary scholars and philosophers have approached this nexus, they have confronted questions about what counts as “philosophy” or “literature,” and what benefits are afforded by conversing across the disciplines. So, as this dialogue continues moving forward, there may be some benefit in also slowing down, pausing, and looking back at the one monograph to expressly locate Coetzee’s writings on a spectrum between literature and philosophy. Although not the most recent publication on the topic, Jan Wilm’s The Slow Philosophy of J.M. Coetzee (2016) merits renewed attention for its use of both literary and philosophical tools in explicating how Coetzee’s texts act upon their readers’ very modes of thinking.

Particularly since the publication of Elizabeth Costello (2003), a strong academic conversation on literature and philosophy has developed around the writings of J.M. Coetzee. As literary scholars and philosophers have approached this nexus, they have confronted questions about what counts as “philosophy” or “literature,” and what benefits are afforded by conversing across the disciplines. So, as this dialogue continues moving forward, there may be some benefit in also slowing down, pausing, and looking back at the one monograph to expressly locate Coetzee’s writings on a spectrum between literature and philosophy. Although not the most recent publication on the topic, Jan Wilm’s The Slow Philosophy of J.M. Coetzee (2016) merits renewed attention for its use of both literary and philosophical tools in explicating how Coetzee’s texts act upon their readers’ very modes of thinking. I am staring

I am staring  April 13, 1947, holds little significance in the American historical memory, and yet that day was one in a long series that led to the legal desegregation of American schools. On that morning, Marguerite Daisy Carr, a 14-year-old black girl from Washington, D.C., attempted to enroll at Eliot Junior High School, the all-white middle school closest to her home. Carr’s efforts to integrate the school, which were supported by her family and local black community, preceded the landmark Supreme Court decision in

April 13, 1947, holds little significance in the American historical memory, and yet that day was one in a long series that led to the legal desegregation of American schools. On that morning, Marguerite Daisy Carr, a 14-year-old black girl from Washington, D.C., attempted to enroll at Eliot Junior High School, the all-white middle school closest to her home. Carr’s efforts to integrate the school, which were supported by her family and local black community, preceded the landmark Supreme Court decision in  4:30 Movie, then, is a book about the general ambience of film, although Masini does invoke specific titles—most notably, the original drive-in version of The Blob (1958), which screened in the 4:30 slot during Masini’s childhood and inspired the title of her book. In the film’s final scene, the hero—“his name was Steve in the movie and Steve in real life,” Masini writes, referring to lead actor Steve McQueen—and the police douse the blob with fire extinguishers to freeze it. A police officer observes that the gelatinous creature can’t be killed but can be stopped. The Air Force drops the blob into the Arctic, and then The End? appears on screen, a playful hint that perhaps the terror isn’t over. Masini is bemused by how hokey and silly the film is, the blob “mindless, deadly, malignant. Amorphous, devouring monster. / Why didn’t we laugh?” But by the end of the poem, she asks herself, “Why am I so frightened?” The whiplash of the question mimics the way viewers abruptly surrender to the magic of film.

4:30 Movie, then, is a book about the general ambience of film, although Masini does invoke specific titles—most notably, the original drive-in version of The Blob (1958), which screened in the 4:30 slot during Masini’s childhood and inspired the title of her book. In the film’s final scene, the hero—“his name was Steve in the movie and Steve in real life,” Masini writes, referring to lead actor Steve McQueen—and the police douse the blob with fire extinguishers to freeze it. A police officer observes that the gelatinous creature can’t be killed but can be stopped. The Air Force drops the blob into the Arctic, and then The End? appears on screen, a playful hint that perhaps the terror isn’t over. Masini is bemused by how hokey and silly the film is, the blob “mindless, deadly, malignant. Amorphous, devouring monster. / Why didn’t we laugh?” But by the end of the poem, she asks herself, “Why am I so frightened?” The whiplash of the question mimics the way viewers abruptly surrender to the magic of film. On almost every page, The Five Quintets praises conversation’s endless interplay—“those evenings when time’s rigid arrow bends,” as we dance from one topic to another. So it’s appropriate that, when I came into New York to discuss the book with O’Siadhail (pronounced “O’sheel”), I first spotted him on a street corner, leaning into a conversation. The seventy-one-year-old O’Siadhail is hard to miss. He has published more than a dozen volumes of poetry, including his eight-hundred-page Collected Poems in 2014, and he looks every inch the poet: tall and handsome, with a craggy face, deep-set eyes, and a hawk-like nose. And there he was, a few blocks from Commonweal’s offices, where we’d agreed to meet, asking a woman where he might grab a bite to eat. He was “feeling a bit peckish,” he later told me, and was thinking about getting a snack. He wasn’t sure if I wanted to talk first and then eat or have lunch and then talk.

On almost every page, The Five Quintets praises conversation’s endless interplay—“those evenings when time’s rigid arrow bends,” as we dance from one topic to another. So it’s appropriate that, when I came into New York to discuss the book with O’Siadhail (pronounced “O’sheel”), I first spotted him on a street corner, leaning into a conversation. The seventy-one-year-old O’Siadhail is hard to miss. He has published more than a dozen volumes of poetry, including his eight-hundred-page Collected Poems in 2014, and he looks every inch the poet: tall and handsome, with a craggy face, deep-set eyes, and a hawk-like nose. And there he was, a few blocks from Commonweal’s offices, where we’d agreed to meet, asking a woman where he might grab a bite to eat. He was “feeling a bit peckish,” he later told me, and was thinking about getting a snack. He wasn’t sure if I wanted to talk first and then eat or have lunch and then talk.