Month: July 2018

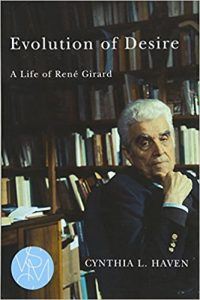

‘Evolution of Desire,’ by Cynthia L. Haven

Rhys Tranter in the San Francisco Chronicle:

Cynthia L. Haven’s “Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard” is the first full-length biography of the acclaimed French thinker. Girard’s “mimetic theory” saw imitation at the heart of individual desire and motivation, accounting for the competition and violence that galvanize cultures and societies. “Girard claimed that mimetic desire is not only the way we love, it’s the reason we fight. Two hands that reach towards the same object will ultimately clench into fists.”

Cynthia L. Haven’s “Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard” is the first full-length biography of the acclaimed French thinker. Girard’s “mimetic theory” saw imitation at the heart of individual desire and motivation, accounting for the competition and violence that galvanize cultures and societies. “Girard claimed that mimetic desire is not only the way we love, it’s the reason we fight. Two hands that reach towards the same object will ultimately clench into fists.”

Often a controversial figure, Girard trespassed into many different fields — he was, by turns, a literary critic, an anthropologist, a sociologist, a psychologist, a theologian and much else besides. Haven’s biography is the first book to contextualize Girard’s work within its proper historical, cultural and philosophical context. The book presumes no prior knowledge, and includes several useful primers of the texts that established his reputation: “Deceit, Desire, and the Novel” (1961), “Violence and the Sacred” (1972), “Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World” (1978), and his study of Shakespeare, “A Theater of Envy” (1991). But it is the author’s closeness to the man once described as the new Darwin of the human sciences” that brings this fascinating biography to life.

Haven was a friend of Girard’s until his death in 2015, and met with family members, friends and colleagues closest to him to prepare for the book.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

I Sing the Body Electric

…..— excerpt

4

I have perceiv’d that to be with those I like is enough,

To stop in company with the rest at evening is enough,

To be surrounded by beautiful, curious, breathing, laughing flesh

… is enough,

To pass among them or touch any one, or rest my arm ever so

… lightly around his or her neck for a moment, what is this then?

I do not ask any more delight, I swim in it as in a sea.

There is something in staying close to men and women and

… looking on them, and in the contact and odor of them, that pleases

… the soul well,

All things please the soul, but these please the soul well.

.

Walt Whitman

from I Sing the Body Electric

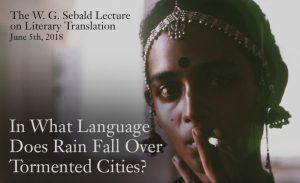

Arundhati Roy: In What Language Does Rain Fall Over Tormented Cities?

Text of The W. G. Sebald Lecture on Literary Translation by Arundhati Roy in Raiot:

At a book reading in Kolkata, about a week after my first novel, The God of Small Things was published, a member of the audience stood up and asked, in a tone that was distinctly hostile:

At a book reading in Kolkata, about a week after my first novel, The God of Small Things was published, a member of the audience stood up and asked, in a tone that was distinctly hostile:

Has any writer ever written a masterpiece in an alien language? In a language other than his mother tongue?

I hadn’t claimed to have written a masterpiece (nor to be a “he”), but nevertheless I understood his anger toward a me, a writer who lived in India, wrote in English, and who had attracted an absurd amount of attention. My answer to his question made him even angrier. “Nabokov,” I said. And he stormed out of the hall.

The correct answer to that question today would of course be “algorithms.” Artificial Intelligence, we are told, can write masterpieces in any language and translate them into masterpieces in other languages. As the era that we know, and think we vaguely understand, comes to a close, perhaps we, even the most privileged among us, are just a group of redundant humans gathered here with an arcane interest in language generated by fellow redundants.

Only a few weeks after the mother tongue/masterpiece incident, I was on a live radio show in London. The other guest was an English historian who, in reply to a question from the interviewer, composed a paean to British imperialism. “Even you,” he said, turning to me imperiously,

the very fact that you write in English is a tribute to the British Empire.

Not being used to radio shows at the time, I stayed quiet for a while, as a well-behaved, recently civilized savage should. But then I sort of lost it, and said some extremely hurtful things.

More here.

Through self-experimentation and posting his genome online, Carl Zimmer learns what heredity really means — and why DNA and lineage are not one and the same

Cathryn J. Prince in The Times of Israel:

Born to an Ashkenazi Jewish father and mother of Irish and German descent, science and heredity has long fascinated Carl Zimmer.

Born to an Ashkenazi Jewish father and mother of Irish and German descent, science and heredity has long fascinated Carl Zimmer.

But when his wife became pregnant with their first child, heredity became a matter of urgency. He wondered what his child would inherit from him and how that inheritance would get passed down to future generations. Being a dedicated science journalist, Zimmer embarked on a quest to decipher the meaning of heredity.

To properly tell the story he knew he needed to delve into one person’s genome. And whose better than his own?

After he had it sequenced, he showed the results to several researchers and had them interpret the findings. He discovered he carries genes for two serious diseases and that he has many identical genes with a typical Nigerian and Chinese person. But perhaps most importantly, Zimmer learned heredity isn’t what we think it is.

More here.

A Sneaky Snapshot

Janet Malcolm at the NYRB:

In Diana and Nikon I reproduced four pictures from The Snapshot to illustrate the new aesthetic. Except that one of the pictures was not actually from the book, but from Gardner’s desk: the snapshot of the couple on the tennis court. The temptation was too great. The gates stood too wide open. When the book appeared, there on pages 70–71, illustrating the work of The Snapshot’s “sophisticated photographers,” was a spread of four pictures with the captions under them of Joel Meyerowitz, Untitled; Robert Frank, Untitled; Nancy Rexroth, Streaming Window, Washington D.C., 1972; and G. Botsford, Untitled, 1971.

The reader may be wondering how this act of mischief could have gone undetected. Didn’t anyone at David Godine, the book’s publisher, notice? Or was the estimable and amiable Godine in on the mischief? As an A.J. Liebling character once said, “memory grows furtive.” I no longer remember how it was done or whether Godine knew.

more here.

Stanley Cavell as Educator

Mark Greif at n+1:

Cavell, rather than being the type of all college professors, turned out to be unique. His tutelage at that time seemed the big experience of my life, and I can’t say that it wasn’t, even now. I was afraid of him, personally—afraid, I mean, of damaging the relation by something personal. I went in later years to his lectures on aesthetics, attended his screenings of operas and films, tried to focus on sessions on Wittgenstein, on language and epistemology.

Cavell, rather than being the type of all college professors, turned out to be unique. His tutelage at that time seemed the big experience of my life, and I can’t say that it wasn’t, even now. I was afraid of him, personally—afraid, I mean, of damaging the relation by something personal. I went in later years to his lectures on aesthetics, attended his screenings of operas and films, tried to focus on sessions on Wittgenstein, on language and epistemology.

I have often asked between then and now what I got myself in for, not that it was Cavell’s fault, not that I wouldn’t have gotten in for it anyway. Nietzsche, when young, advised the initiate, in “Schopenhauer as Educator,” which we read at Cavell’s direction, to cultivate an impersonal self-hatred in order to grow, hating that within yourself which is weak and inferior. It took me more years than it should have to learn that this advice wouldn’t work for me; hatred became personal. (This year, fourteen years later, I saw a note of Nietzsche’s set down when he was fourteen years older: “I wish men would begin by respecting themselves: everything else follows from that. To be sure, as soon as one does this one is finished for others: for this is what they forgive last: ‘What? A man who respects himself?’—”)

more here.

Doom and Gloom: The Role of the Media in Public Disengagement on Climate Change

Elizabeth Arnold at the Shorenstein Center of Harvard University:

In July of 2008, as a national broadcast correspondent, I reported on environmental conditions in Newtok, a remote community of roughly 400 Yup’ik people in Northwest Alaska. Newtok was losing forty to a hundred feet of coastline a year to erosion, and sinking because of “permafrost” that is no longer permanent, the direct result of a warming climate. Flooding threatened homes, the school, and the only supply of clean water. I chose to report on Newtok because the community was actively working on a relocation plan after voting to move to higher, more stable ground. My story compared the actions of Newtok with Kivalina, an Inupiaq community of the same size situated on a barrier island further north. Kivalina faced similar conditions and had filed suit that same year against ExxonMobil Corp. for damages caused by climate change.

In July of 2008, as a national broadcast correspondent, I reported on environmental conditions in Newtok, a remote community of roughly 400 Yup’ik people in Northwest Alaska. Newtok was losing forty to a hundred feet of coastline a year to erosion, and sinking because of “permafrost” that is no longer permanent, the direct result of a warming climate. Flooding threatened homes, the school, and the only supply of clean water. I chose to report on Newtok because the community was actively working on a relocation plan after voting to move to higher, more stable ground. My story compared the actions of Newtok with Kivalina, an Inupiaq community of the same size situated on a barrier island further north. Kivalina faced similar conditions and had filed suit that same year against ExxonMobil Corp. for damages caused by climate change.

In the decade since my report aired on National Public Radio, news outlets from all over the world visited Newtok, Kivalina, Shishmaref, Shaktoolik and a dozen other Alaska Native communities forced to consider relocation because of the effects of climate change. The national stories all fit the same narrative pattern. With images of houses tipping precariously off cliffs, and phrases such as “impending doom,” and “cultural extinction,” the reporting paints a picture of tragedy and hopelessness, framing community members as victims to sell the urgency of mitigation to the public. As a CNN correspondent unabashedly reported, “a trip here is like a trip into a disturbing future.”

The repetition of this narrow narrative in national and international media for more than ten years has not resulted in a groundswell of support for mitigation or adaptation. Nor has it resulted in public policy at the state or federal level. It may have even undermined the ability of these coastal communities to help themselves.

More here.

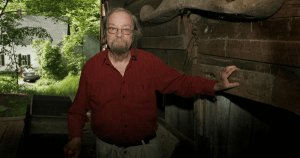

Donald Hall on Eagle Pond

Donald Hall at The American Scholar:

Old houses are full of holes. Creatures sneak into the living room. A summer ago, a garter snake entered and slithered across my living room. I stepped on its head and threw it outside. The same year, I discovered a visitor who became my favorite for persistence. A chipmunk took up residence and remained on the first floor for two or three months. Every day I would hear chirping, at first sounding like an electronic signal. Then the chipmunk came into sight, pausing with its paws tucked or folded before it, I suppose sustained by my cat’s kibble and water. As for my cat, she stared at it intently, fascinated. My housekeeper, Carole, bought a tiny Havahart trap and baited it with whatever we imagined was a chipmunk treat. Every morning the bait was gone, but so was the chipmunk. One morning the creature skittered from the kitchen into the toolshed, where the door showed a wide space at its bottom, and never appeared again. I felt abandoned. When autumn descended into winter, I walked into the cluttered dining room, never used in old age, and smelled something rotten in a box of unsorted snapshots. Under a layer of pictures I found the small body of our chipmunk. It had not escaped after all. With a paper towel I picked it up, rigid and almost weightless, and threw it from the door as far as I could. Next morning when I opened the door to pick up the newspaper, half of his small mummified corpse lay beside the door.

Old houses are full of holes. Creatures sneak into the living room. A summer ago, a garter snake entered and slithered across my living room. I stepped on its head and threw it outside. The same year, I discovered a visitor who became my favorite for persistence. A chipmunk took up residence and remained on the first floor for two or three months. Every day I would hear chirping, at first sounding like an electronic signal. Then the chipmunk came into sight, pausing with its paws tucked or folded before it, I suppose sustained by my cat’s kibble and water. As for my cat, she stared at it intently, fascinated. My housekeeper, Carole, bought a tiny Havahart trap and baited it with whatever we imagined was a chipmunk treat. Every morning the bait was gone, but so was the chipmunk. One morning the creature skittered from the kitchen into the toolshed, where the door showed a wide space at its bottom, and never appeared again. I felt abandoned. When autumn descended into winter, I walked into the cluttered dining room, never used in old age, and smelled something rotten in a box of unsorted snapshots. Under a layer of pictures I found the small body of our chipmunk. It had not escaped after all. With a paper towel I picked it up, rigid and almost weightless, and threw it from the door as far as I could. Next morning when I opened the door to pick up the newspaper, half of his small mummified corpse lay beside the door.

more here.

Sean Carroll’s New Mindscape Podcast: Episode Zero

More details about this exciting project here.

The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading by Edmund White

Rachel Cooke in The Guardian:

Books are so intimate, somehow, and perhaps this is one reason why so many of the current glut of reading memoirs leave me cold. Even as they strain for this sense of disclosure – don’t you feel like this, too? they ask – their tone is proprietorial, hellbent on exceptionality (I love the Brontës even more than you). You would, I think, accept this from a lover, but not from a writer you’ve never met – unless, I will now add, that writer happens to be Edmund White, the tone of whose new book, The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading, quite often resembles the gentle whisper of a sweetheart. Ownership, you see, is not at all his style. In fact, he doesn’t claim always to understand the books that he loves most. “I’ve read it 10 times, though I’m none the wiser for it,” he writes of Anna Karenina, the novel he believes to be the greatest in all of literature.

Books are so intimate, somehow, and perhaps this is one reason why so many of the current glut of reading memoirs leave me cold. Even as they strain for this sense of disclosure – don’t you feel like this, too? they ask – their tone is proprietorial, hellbent on exceptionality (I love the Brontës even more than you). You would, I think, accept this from a lover, but not from a writer you’ve never met – unless, I will now add, that writer happens to be Edmund White, the tone of whose new book, The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading, quite often resembles the gentle whisper of a sweetheart. Ownership, you see, is not at all his style. In fact, he doesn’t claim always to understand the books that he loves most. “I’ve read it 10 times, though I’m none the wiser for it,” he writes of Anna Karenina, the novel he believes to be the greatest in all of literature.

White’s book is a collection of essays, each connecting the seemingly thousands of books he has read – I find it impossible to imagine anyone better read than White, though with typical modesty he insists he knows lots of people who are – to his long writing life (the author of A Boy’s Own Story is now 78). This is done in loose fashion; like any passionate reader, he hops “from one lily pad to another”. Colette cosies up to Jean Cocteau, and Penelope Fitzgerald to Henry Green, and you must therefore concentrate quite hard, particularly in the matter of writers with whose work you are not familiar (in my case, these included two of his favourites, Jean Giono and Pierre Loti). But it’s wonderful, too: wisdom and a certain kind of tenderness are to be found on every page.

More here.

How Long Can We Live? The Limit Hasn’t Been Reached

Carl Zimmer in The New York Times:

Since 1900, average life expectancy around the globe has more than doubled, thanks to better public health, sanitation and food supplies. But a new study of long-lived Italians indicates that we have yet to reach the upper bound of human longevity. “If there’s a fixed biological limit, we are not close to it,” said Elisabetta Barbi, a demographer at the University of Rome. Dr. Barbi and her colleagues published their research Thursday in the journal Science. The current record for the longest human life span was set 21 years ago, when Jeanne Calment, a Frenchwoman, died at the age of 122. No one has grown older since — as far as scientists know. In 2016, a team of scientists at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx made the bold claim that Ms. Calment was even more of an outlier than she seemed. They argued that humans have reached a fixed life span limit, which they estimated to be about 115 years. A number of critics lambasted that research. “The data set was very poor, and the statistics were profoundly flawed,” said Siegfried Hekimi, a biologist at McGill University. Anyone who studies the limits of longevity faces two major statistical challenges. There aren’t very many people who live to advanced ages, and people that old often lose track of how long they’ve actually lived. “At these ages, the problem is to make sure the age is real,” said Dr. Barbi.

Since 1900, average life expectancy around the globe has more than doubled, thanks to better public health, sanitation and food supplies. But a new study of long-lived Italians indicates that we have yet to reach the upper bound of human longevity. “If there’s a fixed biological limit, we are not close to it,” said Elisabetta Barbi, a demographer at the University of Rome. Dr. Barbi and her colleagues published their research Thursday in the journal Science. The current record for the longest human life span was set 21 years ago, when Jeanne Calment, a Frenchwoman, died at the age of 122. No one has grown older since — as far as scientists know. In 2016, a team of scientists at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx made the bold claim that Ms. Calment was even more of an outlier than she seemed. They argued that humans have reached a fixed life span limit, which they estimated to be about 115 years. A number of critics lambasted that research. “The data set was very poor, and the statistics were profoundly flawed,” said Siegfried Hekimi, a biologist at McGill University. Anyone who studies the limits of longevity faces two major statistical challenges. There aren’t very many people who live to advanced ages, and people that old often lose track of how long they’ve actually lived. “At these ages, the problem is to make sure the age is real,” said Dr. Barbi.

…But that’s not what Dr. Barbi and her colleagues found. Among extremely old Italians, they discovered, the death rate stops rising — the curve abruptly flattens into a plateau. The researchers also found that people who were born in later years have a slightly lower mortality rate when they reach 105.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Barbarians

They do not come with furred caps

Smelling of maresmilk, scimitared,

Dour, as tellable as kites.

They live quietly next door,

Speak almost the same language,

Wear almost the same clothes.

Inside the walls. But

Do not think they lack

Precisely the same intentions.

.

John Fowles, 1973

from Poems, John Fowles

Ecco Press, 1973

Tyrants Aren’t Smarter Than Democrats, Just More Evil

by Thomas R. Wells

Tyrants like Vladamir Putin and Kim Jong Un seem to win a lot of their geopolitical contests against democratic governments. How do they do it?

A common explanation is that these tyrants are better at playing the game. They are strategic geniuses leading governments with decades of experience in foreign affairs and characterised by single-mindedness and a long-term horizon. Of course they are going to make better geopolitical moves than democratic governments riven by political factionalism and only able to think as far ahead as the next election.

This explanation is wrong. Tyrants don’t succeed because they are especially skilled at the game of geopolitics, but because they are baddies. Tyrants make bold moves because they are willing to subject their country (and the whole world) to more risk. They can do that because they care less than democrats, and hence worry less, about bringing harms to their people. Like a hedge fund manager, they can afford to take big risks because they are not playing with their own money. When tyrants win it is because of luck, not brilliance. This is easier to see when tyrants lose – as they nearly all do in the end, when their luck runs out.

I. The Clownish Incompetence of Tyranny

The myth of the strategic brilliance of tyrants is driven by cognitive biases. There is the assumption that significant events must have significant agency behind them (the same bias that drives conspiracy thinking). And there is the tendency to fill in the murky mysteries of tyrants’ decision-making by projecting our own worst fears. But if you actually think it through it is rather unlikely that tyrannies would be more competent than democracies, let alone bastions of brilliance. Read more »

Monday Poem

Brevity

I need a good poem

lifespan-short, one

I can shoe-horn between instants

which in that pinch says so much

I’ll understand long and short

by the depth of calluses

they leave on my brain

but it’s not happening

I’m already up to nine lines

so it’s too late for brevity

what I’d like is

one that says something

without rolling on forever

Amazon-like with the

topographical detours

of rivers and streams

or the cul de sacs

of human flaw

but now I see

this is impossible

and won’t end here

in brute summation

like a dead fish

wrapped in newsprint

warning of impending

but once-avoidable

consequence

no, it’ll go on

(who knows why or how long)

until all nouns,

verbs, conjugations,

& absolute clauses

have been spent

until this mine of

memory and metaphor

is no more complete

than the stored meanings,

dragged inside-out

in a flow of pregnant clauses

of blood & breath & bone

that led to others & others & others

like cups spilled into the flow

of the sea-bound flood of

sisters and brothers

Jim Culleny

7/1/18

Means, Medians and Percentiles: Common Statistics Through an Optimization Lens

by Hari Balasubramanian

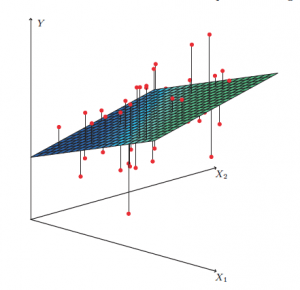

Optimization – the search for the best among many – is at the heart of the statistical and machine learning models that get used so extensively these days. Take the simple concept that underlies many of these models: fitting a mathematical curve to data points, better known as regression. In the simplest two-dimensional case, the curve is a line; in three dimensions, it is a plane, as seen in the figure. Among all possible planes – there are infinitely many of them, obtained by changing the angle and orientation: imagine rotating the plane every which way – we would like the one that passes ‘closest’ to as many of the data points (shown in red) as possible. Thus regression, often called the workhorse of machine learning, is really an optimization problem.

It turns out that optimization is fundamentally connected to even basic statistical quantities. Common statistics we we now reflexively use to summarize data – means, medians and percentiles – are themselves answers to certain optimization questions. We are not used to looking at them in this way.

Let’s take the average or sample mean, which, despite its obvious limitations, everyone turns to first. Suppose we have five numbers in a sample: 3,4,5,8 and 12. The sample mean is given by the straightforward calculation:

(3+4+5+8+12)/5 = 6.4

But there is another way to think of the sample mean: as the optimal answer to the following problem. We seek to find the x that minimizes (produces the lowest value of) the sum of the squared difference between x and each observation in the sample. Mathematically, we can write the function as:

(x-3)2 + (x-4)2 + (x-5)2 + (x-8)2 + (x-12)2

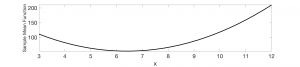

At what value of x does the function have its lowest value? In the figure below, the horizontal axis shows the values that x can take (I restricted myself to the range of the data points, 3 to 12). The vertical axis shows value of the sum of squares function corresponding to each value of x.

We see that the function follows a U-shape with the lowest/best value, x=6.4, occurring at the bottom of the U. Simple high school calculus – finding that point on the continuous curve at which the derivative is 0 – will yield the same answer. In fact, the formula for the mean, adding up all the sample values and dividing by the total number in the sample, can be derived using such calculus. Read more »

Perceptions

Why do people care about sport?

by Emrys Westacott

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

Of course, it’s also true that hundreds of millions don’t give a damn about sport. I know the type: I’m closely related to a disproportionate number of them. To these people, the passion aroused by twenty-two men in shorts trying to force a ball between two sticks is a great mystery, and not something they find it easy to respect. In their view, even if they don’t say this out loud, getting all worked up over a soccer match is a) dumb, and b) good evidence that one needs to get a life. And they may be right. But that still leaves the phenomenon of sport-induced passion unexplained.

Since it is arguably the sporting event that occasions the most consuming passions, let’s focus on the world cup (although many of the points made will naturally apply to other sports also). And let’s distinguish, at the outset, between enjoyment and passion.

Why is soccer entertaining?

It isn’t so hard to understand why soccer provides enjoyable entertainment. First, and most obviously, a good match is dramatic; it has a compelling narrative. But unlike a play or a film, it is unscripted, which means the outcome is not determined in advance, and that makes a game genuinely exciting. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Behind the Oxygen Mask

by Holly Case and Lexi Lerner

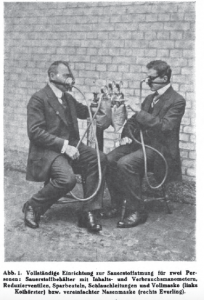

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the oxygen mask—to reveal how our everyday, recorded interactions can acquire extraordinary historical momentum.

“Among the various exploits, vital or destructive, which oxygen can perform, we varnish makers are interested above all in its capacity to react with certain small molecules such as those of certain oils, and of creating links between them, transforming them into a compact and therefore solid network.” —Primo Levi, The Periodic Table (1975)

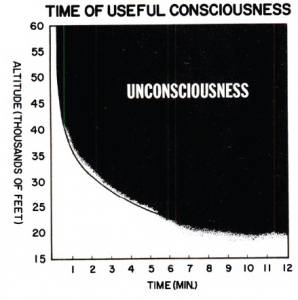

“[A]t 40,000 ft, people have as little as 18 seconds of ‘useful consciousness’ time if they are starved of oxygen. […] [T]he risks of hypoxia–oxygen starvation–are all the greater as people may not realise they are suffering until they can no longer breathe and fall unconscious …” —Lizzie Porter, “What happens when a plane loses cabin pressure?” The Telegraph (Feb. 3, 2016)

“‘Put on your own mask before helping someone else.’ […] I believe this is a metaphor for life.” —Paul Dodd, “The Metaphor of the Airplane Oxygen Mask,” Modern Enlightenment [blog] (May 16, 2015)

***

“Before the oxygen apparatus was used I used to suffer a great deal from flying at high altitudes. […] I used to get this palpitation of the heart and headache when I would fly over 16,000 feet; I would also feel ‘rotten and done up,’ […]” Air Service Medical, War Department, Air Service Division of Military Aeronautics (1919) Read more »