Brian Leiter in the Times Literary Supplement:

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) pursued two main themes in his work, one now familiar, even commonplace in modernity, the other still under-appreciated, often ignored. The familiar Nietzsche is the “existentialist”, who diagnoses the most profound cultural fact about modernity: “the death of God”, or more exactly, the collapse of the possibility of reasonable belief in God. Belief in God – in transcendent meaning or purpose, dictated by a supernatural being – is now incredible, usurped by naturalistic explanations of the evolution of species, the behaviour of matter in motion, the unconscious causes of human behaviours and attitudes, indeed, by explanations of how such a bizarre belief arose in the first place. But without God or transcendent purpose, how can we withstand the terrible truths about our existence, namely, its inevitable suffering and disappointment, followed by death and the abyss of nothingness?

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) pursued two main themes in his work, one now familiar, even commonplace in modernity, the other still under-appreciated, often ignored. The familiar Nietzsche is the “existentialist”, who diagnoses the most profound cultural fact about modernity: “the death of God”, or more exactly, the collapse of the possibility of reasonable belief in God. Belief in God – in transcendent meaning or purpose, dictated by a supernatural being – is now incredible, usurped by naturalistic explanations of the evolution of species, the behaviour of matter in motion, the unconscious causes of human behaviours and attitudes, indeed, by explanations of how such a bizarre belief arose in the first place. But without God or transcendent purpose, how can we withstand the terrible truths about our existence, namely, its inevitable suffering and disappointment, followed by death and the abyss of nothingness?

Nietzsche the “existentialist” exists in tandem with an “illiberal” Nietzsche, one who sees the collapse of theism and divine teleology as tied fundamentally to the untenability of the entire moral world view of post-Christian modernity.

More here.

In 1890, just over six thousand people lived in the damp lowlands of south

In 1890, just over six thousand people lived in the damp lowlands of south  EARLY IN THE MORNING

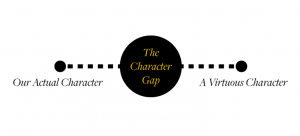

EARLY IN THE MORNING Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world. Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for. Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth.

Here is the predicament that most of us seem to be in. We are not virtuous people. We simply do not have characters that are good enough to qualify as honest, compassionate, wise, courageous, and the like. We are not vicious people either—dishonest, callous, foolish, cowardly, and so forth. Rather we have a mixed character with some good sides and some bad sides. This is the most plausible interpretation of what psychology tells us. It is also true to our lived experience in the world. Those are the facts as I see them. Now comes the value judgment—this is a real shame. It is very unfortunate that our characters are this way. It is a good thing—indeed, a very good thing—to be a good person. Excellence of character, or being virtuous, is what we should all strive for. Admittedly, the news is not all bad. It would be a lot worse if most of us were vicious people. Imagine what it would be like to live in a world full of mostly cruel, self-centered, dishonest, and hateful people. It would be hell on earth. What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.” Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them. Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage.

What strategies are there to try to develop a better character, and which of these strategies show substantial promise? In my book The Character Gap: How Good Are We?, I consider a number of different strategies. One I find quite interesting is what we might call “virtue labeling.” Suppose you come to believe, as I do, that most of the people we know do not have any of the virtues. So your friend, your boss, your neighbor … you need to change your opinion of all of them. Now here is the interesting idea—even with this new outlook firmly in mind, you should still go ahead and call them honest people next time you see them. You should still praise them for being compassionate. You should go out of your way to comment on their courage.