Month: July 2018

Speciation far from the madding crowd

Mooers and Greenberg in Nature:

The tropics are, like many cities, hot, busy and crowded. It was previously thought1 that these conditions in the tropics generate a hotbed for the formation of new species (speciation). Species diversity is remarkably high in the tropics and declines toward the poles. However, newly developed tools to measure speciation rates, coupled with ever-growing global data sets, have enabled the surprising finding that terrestrial speciation rates for the past few million years are similar across different latitudes2 or increase outside the tropics3. Writing in Nature, Rabosky et al.4 document a speciation rate for marine fishes at high latitudes that is twice the speciation rate in tropical seas. This high speciation rate in cold, species-poor waters poses an interesting conundrum for evolutionary biologists and ecologists.

The tropics are, like many cities, hot, busy and crowded. It was previously thought1 that these conditions in the tropics generate a hotbed for the formation of new species (speciation). Species diversity is remarkably high in the tropics and declines toward the poles. However, newly developed tools to measure speciation rates, coupled with ever-growing global data sets, have enabled the surprising finding that terrestrial speciation rates for the past few million years are similar across different latitudes2 or increase outside the tropics3. Writing in Nature, Rabosky et al.4 document a speciation rate for marine fishes at high latitudes that is twice the speciation rate in tropical seas. This high speciation rate in cold, species-poor waters poses an interesting conundrum for evolutionary biologists and ecologists.

There are two potential drivers of high speciation rates in the tropics. First, the elevated temperatures in the region both speed up metabolism, increasing the number of mutations, and decrease generation times. This is a potentially powerful combination, producing more of the variation necessary for evolution and the possibility of faster evolution. A second possible driver is ecological opportunity. The energy-rich tropics offer abundant resources that can support many different niches. And the tropics are so rich in species that the interactions of members of a single species with its competitors, predators and parasites might differ from place to place, leading to different adaptations and eventual divergence into new niches1. Although this narrative makes for a compelling theory, Rabosky and colleagues’ discovery suggests a different story, at least for marine fishes.

More here.

Friday Poem

Foundations

I built on the sand

And it tumbled down,

I built on rock

And it tumbled down.

Now when I build, I shall begin

With the smoke from the chimney.

.

Leopold Staff

from A Book of Luminous Things

translation from Polish by Czeslaw Milosz

Harcourt, 1996

The Philosopher of the Firework

Skye C. Cleary and John Kaag in the Paris Review:

Fireworks, hypnotic and sublime, are used to celebrate national independence around the globe, as signs of sovereignty or political autonomy. They are the window dressing of the modern state. The exploding rainbows are a tribute to the bloody wars that made the celebration possible. They are a reminder that—under that same sky and upon that same land to which the ashes float—we are kinfolk.

Fireworks, hypnotic and sublime, are used to celebrate national independence around the globe, as signs of sovereignty or political autonomy. They are the window dressing of the modern state. The exploding rainbows are a tribute to the bloody wars that made the celebration possible. They are a reminder that—under that same sky and upon that same land to which the ashes float—we are kinfolk.

There is exactly one European thinker who could be considered the “philosopher of the firework”: Friedrich Nietzsche. “I am dynamite!” Nietzsche wrote in Ecce Homo. Dynamite, from dunamis, meaning power. Nietzsche, more than any other contemporary thinker, grappled with the draw and the danger of a fiery blaze.

Born into a nineteenth-century culture that throbbed with German nationalism, Nietzsche was well aware of how such a spectacle—beautiful and potentially disastrous—could influence people.

More here.

Thomas Bayes and the crisis in science

David Papineau in the Times Literary Supplement:

We are living in new Bayesian age. Applications of Bayesian probability are taking over our lives. Doctors, lawyers, engineers and financiers use computerized Bayesian networks to aid their decision-making. Psychologists and neuroscientists explore the Bayesian workings of our brains. Statisticians increasingly rely on Bayesian logic. Even our email spam filters work on Bayesian principles.

We are living in new Bayesian age. Applications of Bayesian probability are taking over our lives. Doctors, lawyers, engineers and financiers use computerized Bayesian networks to aid their decision-making. Psychologists and neuroscientists explore the Bayesian workings of our brains. Statisticians increasingly rely on Bayesian logic. Even our email spam filters work on Bayesian principles.

It was not always thus. For most of the two and a half centuries since the Reverend Thomas Bayes first made his pioneering contributions to probability theory, his ideas were side-lined. The high priests of statistical thinking condemned them as dangerously subjective and Bayesian theorists were regarded as little better than cranks. It is only over the past couple of decades that the tide has turned. What tradition long dismissed as unhealthy speculation is now generally regarded as sound judgement.

More here.

Hospitalism

Sarah Perry in the London Review of Books:

In the small hours of a spring morning last year I asked for a hot-water bottle to be put on my calf: a ruptured disc was crushing my sciatic nerve, causing leg pain unappeased by opioids and benzodiazepines. I went back to sleep. When I woke up, I felt a damp substance on my leg, and when I wiped it off, I noticed a wet white rag was hanging from my fingertips. I thought little of it: pain was my sole preoccupation at the time, and there wasn’t any. Later that day, awaiting surgery, I was told the hot-water bottle had caused a burn clean through the epidermis, cauterising the nerves.

In the small hours of a spring morning last year I asked for a hot-water bottle to be put on my calf: a ruptured disc was crushing my sciatic nerve, causing leg pain unappeased by opioids and benzodiazepines. I went back to sleep. When I woke up, I felt a damp substance on my leg, and when I wiped it off, I noticed a wet white rag was hanging from my fingertips. I thought little of it: pain was my sole preoccupation at the time, and there wasn’t any. Later that day, awaiting surgery, I was told the hot-water bottle had caused a burn clean through the epidermis, cauterising the nerves.

The burn became a black disc so tough you could rap it like the cover of a leather-bound book; I fretted about scarring, but what concerned the doctors was the possibility of my acquiring one of the antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria that plague hospital wards. Two weeks later – the necrotic flesh had receded to reveal body fat resembling butter softened in the microwave – a GP peeled the dressing off, lifted it to her nose, and recoiled at the unmistakeable smell of infection. Swabs were taken, but it was merely the Staphylococcus aureus bacterium, its name deriving from the Greek for ‘grape-cluster berry’, which it resembles. A course of antibiotics, frequent sluicings with saline, and all would be well.

In the days of Lister, Liston and Pasteur, such infections were thought to be an example of what was known as ‘hospitalism’, for the better prevention of which it was even proposed that all hospitals should be razed by fire and rebuilt every ten years or so.

More here.

This amazing cure for cancer has been known since the 1800s

On The Poems of Geoffrey Hill

Paul Bachelor at Poetry Magazine:

As many critics have noted, Hill established himself from the beginning as an elegist. The title For the Unfallen promises a

memorial for the living, and the book itself contains “In Memory of Jane Fraser,” “Requiem for the Plantagenet Kings,” “Two Formal Elegies,” “In Piam Memoriam,” “Wreaths,” “Elegiac Stanzas,” and “Of Commerce and Society” (a series of memorials for Shelley, the Titanic, and St. Sebastian, among others). Each of these elegies is grounded in a particular historical moment. A close engagement with history — itself a form of respectful acknowledgment to the dead — will become another unifying characteristic of Hill’s career.

As many critics have noted, Hill established himself from the beginning as an elegist. The title For the Unfallen promises a

memorial for the living, and the book itself contains “In Memory of Jane Fraser,” “Requiem for the Plantagenet Kings,” “Two Formal Elegies,” “In Piam Memoriam,” “Wreaths,” “Elegiac Stanzas,” and “Of Commerce and Society” (a series of memorials for Shelley, the Titanic, and St. Sebastian, among others). Each of these elegies is grounded in a particular historical moment. A close engagement with history — itself a form of respectful acknowledgment to the dead — will become another unifying characteristic of Hill’s career.

Such engagement moves center stage in Hill’s second collection, King Log (1968), with the astonishing sonnet sequence “Funeral Music,” which is dedicated to William de la Pole, John Tiptoft, and Anthony Woodville: aristocrats executed during the Wars of the Roses.

more here.

The Complexities of Laura Ingalls Wilder

Terri Apter at the TLS:

Laura Ingalls Wilder, the author of eight novels – published between 1932 and 1943 – about pioneer life in the American west, was the first recipient of a major children’s book award (which bestowed on her the additional honour of bearing her name): the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal. On June 23, the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) voted unanimously to strip her name from the award, stating that Wilder “includes expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with ALSC’s values”.

Laura Ingalls Wilder, the author of eight novels – published between 1932 and 1943 – about pioneer life in the American west, was the first recipient of a major children’s book award (which bestowed on her the additional honour of bearing her name): the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal. On June 23, the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) voted unanimously to strip her name from the award, stating that Wilder “includes expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with ALSC’s values”.

My response – an uneasy sense of loss – is partly, but only partly, due to the role Wilder’s novels played in my own life. As the less compliant little sister, I cheered Laura with her irritability and impatience, alongside the great love she had for the sister who seemed to outshine her.

more here.

The Rare Women in the Rare Book Trade

Diane Mehta at The Paris Review:

Like many women, Baskin was buying things that male dealers weren’t interested in, such as women printers and artists, which put her under the radar. “In the sixties, I could be a ferret and find things,” she said, citing a late 17th century-early 18th century book by Maria Sibylla Merian, the first person of either gender to observe and draw the metamorphoses of insects in the field. “She made some of the most beautiful books,” Baskin said. “As a child, Merian was fascinated by watching caterpillars turn into moths. She made a book about the insects of Suriname and another about the insects of Europe.” Baskin purchased a copy of Merian’s De Europische Insecten (1730); copies of the book about the insects of Suriname go for hundreds of thousands of dollars now. “The issue is: Are women taken seriously as dealers and as collectors? I don’t think it’s a reflection on the works they sell or collect. I think these works were, and are, valued less,” says Baskin. She mentions J.P. Morgan’s (d. 1913) great Morgan Library, whose collection—of books by both men and women—was largely acquired by its director and librarian Belle da Costa Greene, daughter of the first African American to graduate from Harvard. “It was said that da Costa Greene had the brains and the wit and Morgan had the money,” Baskin says.

Like many women, Baskin was buying things that male dealers weren’t interested in, such as women printers and artists, which put her under the radar. “In the sixties, I could be a ferret and find things,” she said, citing a late 17th century-early 18th century book by Maria Sibylla Merian, the first person of either gender to observe and draw the metamorphoses of insects in the field. “She made some of the most beautiful books,” Baskin said. “As a child, Merian was fascinated by watching caterpillars turn into moths. She made a book about the insects of Suriname and another about the insects of Europe.” Baskin purchased a copy of Merian’s De Europische Insecten (1730); copies of the book about the insects of Suriname go for hundreds of thousands of dollars now. “The issue is: Are women taken seriously as dealers and as collectors? I don’t think it’s a reflection on the works they sell or collect. I think these works were, and are, valued less,” says Baskin. She mentions J.P. Morgan’s (d. 1913) great Morgan Library, whose collection—of books by both men and women—was largely acquired by its director and librarian Belle da Costa Greene, daughter of the first African American to graduate from Harvard. “It was said that da Costa Greene had the brains and the wit and Morgan had the money,” Baskin says.

more here.

Thursday Poem

The Mother’s Seduction

—for Emily Dickinson

I christen you my mother, and you,

Like her, refuse to give straight answers-

She, silent; you, forever talking slant.

And I’ve exhausted all questions except

The one to which I am answer

And therefore cannot form.

You deal your words like blades or cards

And to keep the game mysterious

You won’t divulge the rules. I never win.

And if I come to you because much time

Has passed since my last meal, you tell a tale

About a crumb that you and Robin feast

Upon, leaving some for charity.

I know it is not true still I believe.

“There’s a pair of us,” you say, “don’t tell-”

And I will keep your secret much too long

Because the racket of this living shames

Me too. The guiltless are not innocent.

I want to lose this innocence, leave

All guilt behind, learn to live loudly,

Become someone, but you won’t tell me how.

I cannot live as you before me did.

It is another time, another place,

A different set of circumstances,

A different work to live.

We have no rest to give each other.

The leaves they turn and turn. With tenderness

I touch you out of sleep; I wake to your

Wild words: much madness is divinest sense.

We cannot reach each other now though I,

Too, dwell in possibility. Escape

Is on my tongue, still, I can no more run

Away from you than crawl into your arms

by Constance Merritt

from A Protocol for Touch

University of North Texas Press, 1999

Tomorrow’s Earth

Jeremy Berg in Science:

Our planet is in a perilous state. The combined effects of climate change, pollution, and loss of biodiversity are putting our health and well-being at risk. Given that human actions are largely responsible for these global problems, humanity must now nudge Earth onto a trajectory toward a more stable, harmonious state. Many of the challenges are daunting, but solutions can be found. In this issue of Science, we launch a series of monthly articles that call attention to some of the choices we can still make for shaping tomorrow’s Earth—commentaries and analyses that will hopefully provoke us to making thoughtful choices (see scim.ag/TomorrowsEarth).

Our planet is in a perilous state. The combined effects of climate change, pollution, and loss of biodiversity are putting our health and well-being at risk. Given that human actions are largely responsible for these global problems, humanity must now nudge Earth onto a trajectory toward a more stable, harmonious state. Many of the challenges are daunting, but solutions can be found. In this issue of Science, we launch a series of monthly articles that call attention to some of the choices we can still make for shaping tomorrow’s Earth—commentaries and analyses that will hopefully provoke us to making thoughtful choices (see scim.ag/TomorrowsEarth).

Many of today’s challenges can be traced back to the“Tragedy of the Commons”identified by Garrett Hardin in his landmark essay, published in Science 50 years ago. Hardin warned of a coming population–resource collision based on individual self-interested actions adversely affecting the common good. In 1968, the global population was about 3.5 billion; since then, the human population has more than doubled, a rise that has been accompanied by large-scale changes in land use, resource consumption, waste generation, and societal structures. Science‘s “State of the Planet” articles (published between 2003 and 2008; see scim.ag/StateofthePlanet) articulated the stresses and possible solutions to these growing human-induced impacts on the Earth system. Donald Kennedy, then Science‘s Editor-in-Chief, aptly asserted: “The big question in the end is not whether science can help. Plainly it could. Rather, it is whether scientific evidence can successfully overcome social, economic, and political resistance.”

Through collective action, we can indeed achieve planetary-scale mitigation of harm. A case in point is the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, the first treaty to achieve universal ratification by all countries in the world. In the 1970s, scientists had shown that chemicals used as refrigerants and propellants for aerosol cans could catalyze the destruction of ozone. Less than a decade later, these concerns were exacerbated by the discovery of seasonal ozone depletion over Antarctica. International discussions on controlling the use of these chemicals culminated in the Montreal Protocol in 1987. Three decades later, research has shown that ozone depletion appears to be decreasing in response to industrial and domestic reforms that the regulations facilitated.

More here.

The amazing life and reign of Nur Jahan

Randy Dotinga in The Christian Science Monitor:

If you grew up in South Asia, the lush 17th-century romance of a captivating young widow and a Moghul emperor is likely as familiar to you as Romeo & Juliet are in the West. They meet, and she wows the ruler of tens of millions of people with her beauty, wit, and fearlessness. Wise and savvy, she becomes his beloved 20th wife and goes on to live an extraordinary life. She writes poetry, designs gardens and buildings, and even saves a village by hunting down and killing four dangerous tigers with six shots. That’s as far as the legend and the history books tend to go. But there’s much more to the story, as historian Ruby Lal reveals in her fascinating new book Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan.

If you grew up in South Asia, the lush 17th-century romance of a captivating young widow and a Moghul emperor is likely as familiar to you as Romeo & Juliet are in the West. They meet, and she wows the ruler of tens of millions of people with her beauty, wit, and fearlessness. Wise and savvy, she becomes his beloved 20th wife and goes on to live an extraordinary life. She writes poetry, designs gardens and buildings, and even saves a village by hunting down and killing four dangerous tigers with six shots. That’s as far as the legend and the history books tend to go. But there’s much more to the story, as historian Ruby Lal reveals in her fascinating new book Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan.

While some historians dismiss the idea that Nur Jahan was anything but a royal consort, Lal contends that she served as co-sovereign with her husband while living in a harem. In a culture of male dominance, Lal writes, “a new kind of power was on display.” “The basic facts,” Lal said in a Monitor interview, “are pretty astounding. To put it plainly, she was the one woman we can count among the great rulers of India.”

Q: What drew you to Nur Jahan, a Shiite Muslim from an immigrant Iranian family who marries a Sunni Muslim who is half-Hindu?

This is a woman who was clearly bold, independent, and very inventive in challenging the norm in quite extraordinary ways. For me as a historian of India, the empress is not an add-on. She is the story of India. Once you know about people like her, you turn your head and see things differently. You see a place of creative, living, dynamic, influential women.

More here.

The Irrepressible Human Voice of Stanley Cavell

Jonathan Tran at The Marginalia Review of Books:

Inasmuch as he had a specialization, Cavell’s was our human life in words and he, along with Cora Diamond and James Conant, is credited with giving second life to a hitherto expiring mode of thought known as ordinary language philosophy. Cavell was fascinated by how language proves constitutive of what it means to be human, and was further fascinated by how much we humans want to deny that—probably, he thought, because of what the implications would demand of us. In a characteristically exquisite passage from the legendary fourth part of The Claim of Reason, Cavell wrote, “There is no assignable end to the depth of us to which language reaches; that nevertheless there is no end to our separateness. We are endlessly separate, for no reason. But then we are answerable for everything that comes between us; if not for causing it then for continuing it; if not for denying it then for affirming it; if not for it then to it.”

Inasmuch as he had a specialization, Cavell’s was our human life in words and he, along with Cora Diamond and James Conant, is credited with giving second life to a hitherto expiring mode of thought known as ordinary language philosophy. Cavell was fascinated by how language proves constitutive of what it means to be human, and was further fascinated by how much we humans want to deny that—probably, he thought, because of what the implications would demand of us. In a characteristically exquisite passage from the legendary fourth part of The Claim of Reason, Cavell wrote, “There is no assignable end to the depth of us to which language reaches; that nevertheless there is no end to our separateness. We are endlessly separate, for no reason. But then we are answerable for everything that comes between us; if not for causing it then for continuing it; if not for denying it then for affirming it; if not for it then to it.”

There is an emancipatory tone to Cavell’s writing, licensing in his readers intellectual possibilities they did not know existed. The somewhat religious devotion of his academic followers, including the many religious ones, can in part be explained by how his work reconciles them to the impulses that drove them to take up teaching and writing in the first place.

more here.

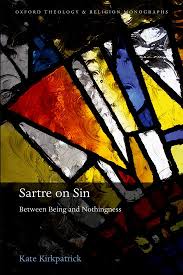

Sartre on Sin

Kate Kirkpatrick at Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews:

Kate Kirkpatrick’s provocative interdisciplinary study argues that Sartre’s conception of nothingness in Being and Nothingness (BN) can be fruitfully understood as an iteration of the Christian doctrine of original sin, “nothingness” being synonymous with sin and evil in the Augustinian tradition. Hence, Sartre in BN presents us with “a phenomenology of sin from a graceless position” (10). For readers used to understanding Sartre through the lens of German phenomenology, this will come as a surprise. However, the book should be welcomed by all readers as it breathes life into the field of Sartre studies, offering a fresh perspective from which to judge the magnum opus of French existentialism.

Kate Kirkpatrick’s provocative interdisciplinary study argues that Sartre’s conception of nothingness in Being and Nothingness (BN) can be fruitfully understood as an iteration of the Christian doctrine of original sin, “nothingness” being synonymous with sin and evil in the Augustinian tradition. Hence, Sartre in BN presents us with “a phenomenology of sin from a graceless position” (10). For readers used to understanding Sartre through the lens of German phenomenology, this will come as a surprise. However, the book should be welcomed by all readers as it breathes life into the field of Sartre studies, offering a fresh perspective from which to judge the magnum opus of French existentialism.

Kirkpatrick is not the first to address Sartre’s relation to theology or to note similarities between Sartre’s ideas in BN and the doctrine of original sin. Her forerunners include Merold Westphal’s Suspicion and Faith: The Religious Uses of Modern Atheism (1998), Stephen Mulhall’s Philosophical Myths of the Fall (2005), and several articles by John Gillespie published in Sartre Studies International. She is, however, the first to pursue the topic in depth. Kirkpatrick’s earlier book, Sartre and Theology (2017), which examines Sartre’s engagement with theology more broadly, could be a useful background resource for readers of this one.

more here.

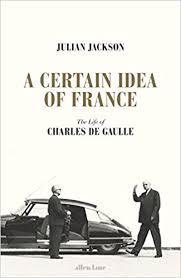

The Life of Charles de Gaulle

Richard Viven at Literary Review:

Who was Charles de Gaulle? Stop the clock in 1939 and he was an eccentric army officer. Stop it in July 1940, after he had flown to London, and he was claiming to represent France against the Vichy regime – though some Englishmen admired this right-wing Catholic because they thought of him as almost as much of an opponent of the Third Republic as he was of the Vichy state. Stop the clock in 1945 and he was head of the French government, supported by republicans and even communists. Stop it a year later and he had resigned in a huff; his career was apparently over. The British ambassador to Paris wrote: ‘On … the eve of the anniversary of Louis XVI’s execution, General de Gaulle cut off his own head and passed into the shadow-land of politics.’ In 1958 he was back in power, mainly because the army hoped that he would preserve French Algeria. Four years after this, he withdrew French forces from Algeria, claiming that this was what he had always intended to do. Some of his numerous right-wing enemies responded to his ‘treason’ with a succession of assassination attempts. By the mid-1960s, he was presiding over a prosperous and stable country. Then, in May 1968, faced with a student uprising, he seemed to totter on the edge of the abyss before restoring his grip on power by presenting himself as a defender of order. However, perhaps because he never felt comfortable as a conventional conservative, he resigned the following year.

Who was Charles de Gaulle? Stop the clock in 1939 and he was an eccentric army officer. Stop it in July 1940, after he had flown to London, and he was claiming to represent France against the Vichy regime – though some Englishmen admired this right-wing Catholic because they thought of him as almost as much of an opponent of the Third Republic as he was of the Vichy state. Stop the clock in 1945 and he was head of the French government, supported by republicans and even communists. Stop it a year later and he had resigned in a huff; his career was apparently over. The British ambassador to Paris wrote: ‘On … the eve of the anniversary of Louis XVI’s execution, General de Gaulle cut off his own head and passed into the shadow-land of politics.’ In 1958 he was back in power, mainly because the army hoped that he would preserve French Algeria. Four years after this, he withdrew French forces from Algeria, claiming that this was what he had always intended to do. Some of his numerous right-wing enemies responded to his ‘treason’ with a succession of assassination attempts. By the mid-1960s, he was presiding over a prosperous and stable country. Then, in May 1968, faced with a student uprising, he seemed to totter on the edge of the abyss before restoring his grip on power by presenting himself as a defender of order. However, perhaps because he never felt comfortable as a conventional conservative, he resigned the following year.

more here.

What Did the Founding Fathers Eat and Drink as They Started a Revolution?

Amanda Cargill in Smithsonian:

As we commence celebrating July 4th with the time-honored traditions of beer, block parties and cookouts, it’s fun to imagine a cookout where the Founding Fathers gathered around a grill discussing the details of the Declaration of Independence. Did George Washington prefer dogs or burgers? Was Benjamin Franklin a ketchup or mustard guy? And why did they all avoid drinking water?

As we commence celebrating July 4th with the time-honored traditions of beer, block parties and cookouts, it’s fun to imagine a cookout where the Founding Fathers gathered around a grill discussing the details of the Declaration of Independence. Did George Washington prefer dogs or burgers? Was Benjamin Franklin a ketchup or mustard guy? And why did they all avoid drinking water?

…George Washington was exceedingly fond of dining on seafood. For nearly 40 years, the three fisheries he operated along the ten-mile Potomac shoreline that bordered Mount Vernon processed more than a million fish annually. Among the items on the plantation’s menu were crabmeat casseroles, oyster gumbos and salmon mousse.

Thomas Jefferson admired French fare above all, and he is credited, according to Staib, with popularizing frites, ice cream and champagne. He is also often credited—although incorrectly—with the introduction of macaroni and cheese to the American palate. It was, in fact, his enslaved chef James Hemings who, via Jefferson’s kitchen, brought the creamy southern staple to Monticello. Trained at the elite Château de Chantilly while accompanying Jefferson on a trip to France, Hemings would later become one of only two laborers enslaved by Jefferson to negotiate his freedom.

As for dessert, none of the Founding Fathers was without a sweet tooth. John Adams’ wife, Abigail, regularly baked Apple Pan Dowdy, a pie-meets-cobbler hybrid that was popular in New England in the early 1800s; James Madison loved ice cream and was spoiled by his wife Dolley’s creative cakes, for which she gained such renown that, to this day, supermarkets across America carry a brand of prepared pastries bearing her—albeit incorrectly spelled—name; and John Jay, in a letter sent to his father in 1790, reported that he carried chocolate with him on long journeys, likely “shaving or grating it into pots of milk,” says Kevin Paschall, chocolate maker at Philadelphia’s historic Shane Confectionery, and consuming it as a drink.

More here.

Seeing Art in Medical Archives

Roslyn Bernstein in Guernica:

A striking show of sculpture from 14th century Europe to the present, Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body, currently on view at the Met Breuer, is full of surprises. How, the show asks repeatedly, did artists over the centuries depict the human body? Works of art that we expect to find in art museums are juxtaposed with much more jarring examples—in many cases, objects not traditionally seen as art at all. There are casts taken from real bodies; paint applied to works of art to imitate flesh tones. There are works with human blood, hair, teeth, and bones. One of the most shocking is The Digger (1857-1858) by Alphonse Lami, where the flayed figure’s (écorché) life-size body is so realistic that we see all the details of his musculature. He is leaning on his shovel but he hardly seems to be working. His body is painted red, with a sheen that radiates from what seem to be medically delineated tendons. The Met Breuer’s website reminds us that although most écorchés were created as anatomical teaching models for students of painting and sculpture, Lami “conceived of this figure as a genuine work of art, exhibiting it at the Parisian Salon of 1857 and signing its bronze base before it was subsequently displayed at the Académie des Sciences.”

A striking show of sculpture from 14th century Europe to the present, Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body, currently on view at the Met Breuer, is full of surprises. How, the show asks repeatedly, did artists over the centuries depict the human body? Works of art that we expect to find in art museums are juxtaposed with much more jarring examples—in many cases, objects not traditionally seen as art at all. There are casts taken from real bodies; paint applied to works of art to imitate flesh tones. There are works with human blood, hair, teeth, and bones. One of the most shocking is The Digger (1857-1858) by Alphonse Lami, where the flayed figure’s (écorché) life-size body is so realistic that we see all the details of his musculature. He is leaning on his shovel but he hardly seems to be working. His body is painted red, with a sheen that radiates from what seem to be medically delineated tendons. The Met Breuer’s website reminds us that although most écorchés were created as anatomical teaching models for students of painting and sculpture, Lami “conceived of this figure as a genuine work of art, exhibiting it at the Parisian Salon of 1857 and signing its bronze base before it was subsequently displayed at the Académie des Sciences.”

The timing of my visit to Like Life was fortuitous. I was on my way to Italy with friends, one of them Professor Bert Hansen, a historian of medicine, whose research trip involved visits to anatomical theaters, medical museums, and archives, which housed collections that journalists rarely saw. Before Italy, though, I made a short stop in Pittsburgh and saw It’s all about ME, Not You, the Greer Lankton installation at The Mattress Factory on the city’s North Side. The bald-headed doll-mannequin on the posters for the Like Life show in New York was actually a Lankton work: a papier-mâché doll of the performance artist Rachel Rosenthal, which was once hung, fully clothed, in a store window in the East Village. Hairless, her rib bones protruding from her emaciated chest and harshly made up with red lipstick, arched eyebrows, and long red nails, the androgynous figure stares off into the distance with a stern, sad look. Here is another exhibit that focuses on the human body, in this case on Lankton’s, and on her life as a transgender woman.

More here.

Bruno Latour Tracks Down Gaia

Bruno Latour in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

I WAS TOLD by Stephan Harding that “if there was the slightest chance of a cold, we will have to cancel. He had bronchitis not long ago; we can’t afford to take any risks.” But, despite the Arctic cold that had descended on England in February, I wasn’t coughing or anything, so we decided to embark. Nevertheless, we took the precaution of washing our hands carefully with antiseptic soap a few times. And then we were off for the coast of Dorset, in the south of England, in the direction of Cornwall.

I WAS TOLD by Stephan Harding that “if there was the slightest chance of a cold, we will have to cancel. He had bronchitis not long ago; we can’t afford to take any risks.” But, despite the Arctic cold that had descended on England in February, I wasn’t coughing or anything, so we decided to embark. Nevertheless, we took the precaution of washing our hands carefully with antiseptic soap a few times. And then we were off for the coast of Dorset, in the south of England, in the direction of Cornwall.

At 98, James Lovelock is a very old man. His thinking is all the more important in that it avoids the academic, and he was the first to theorize what in ecology and Earth sciences is called the “Gaia” hypothesis, which I can provisionally summarize at this stage of my inquiry: the Earth is a totality of living beings and materials that were made together, that cannot live apart, and from which humans can’t extract themselves.

I had never imagined I would meet the father of Gaia. I had read all his books, but I was not all that keen on his recent statements in the press, his somewhat bizarre political ideas, and his inflated enthusiasm for the nuclear industry. Nor was I one for visiting the places where my favorite authors wrote their books. But Harding, his friend and disciple, had assured me that Lovelock wanted to meet me. He was wondering why a French philosopher was interested enough in the Gaia theory to devote a whole book to it [Bruno Latour’s Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, was published by Polity in 2017].

More here. [Thanks to Asad Raza.]

Why haven’t we found aliens yet?

Liv Boeree in Vox:

One summer night, when I was a child, my mother and I were scouring the night sky for stars, meteors, and planets.

One summer night, when I was a child, my mother and I were scouring the night sky for stars, meteors, and planets.

Suddenly, an object with a light that pulsed steadily from bright to dim caught my eye. It didn’t have the usual red blinkers of an aircraft and was going far too slowly to be a shooting star.

Obviously, it was aliens.

My excitement was short-lived as my mother explained it was a satellite catching the sun as it tumbled along its orbit. I went to bed disappointed: The X-files was on TV twice a week back then, and I very much wanted to believe.

Today that hope is still alive and well, in Hollywood films, the public imagination, and even among scientists. Scientists first began searching for alien signals shortly after the advent of radio technology around the turn of the 20th century, and teams of astronomers across the globe have been taking part in the formal Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) since the 1980s.

Yet the universe continues to appear devoid of life.

Now, a team of researchers at the University of Oxford brings a new perspective to this conundrum.

More here.