by Timothy Don

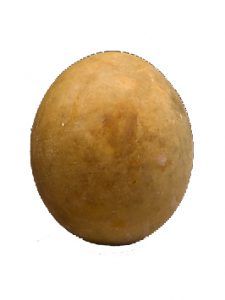

Speak the word “discovery” and familiar images of explorers, scientists, ships, and treasure chests come to mind. To look into the visual record of “discovery” over the past 50,000 years, however, is to witness the concept expand, swell, and overwhelm the imagination. There is a wonder that arises in the wake of one’s research with the realization that the deeper and closer one looks, the wider, richer, and more capacious the topic at hand becomes. Consider the egg.

A simple egg. The familiarity of its shape is unnerving, even disarming. Hovering there, alone in space, it has the weight of a moon or a planet. A red planet. A symbol of discovery in its expansive, exploratory sense: to discover is to reach out into space, to land on the moon, to plan for Mars. But…this object is not Mars. It is an egg. It is an ostrich egg, more than 5,000 years old, from the predynastic period of Northern Upper Egypt, dug out of a tomb. Mars remains undiscovered. This is an artifact from an era now lost to us, uncovered by a forgotten Egyptologist from the 19th century. It belongs to the past. This is an actual discovery. And it is wonderful. It is pure potential. It has been discovered, but it remains uncracked. Full of mystery, this old egg from the past, it fills you with wonder. At that moment a gestalt switch gets thrown, and one realizes that discovery’s arrow points not only forward and outward to unexplored planets, but backward and inward to things lost, buried, and forgotten. To discover a thing is also to discover the past, and the act of discovery is about the recovery of the past just as much as it is about the probing of the future. And so a planet (symbol of the undiscovered future) becomes an artifact (material expression of the discovered past), and the artifact (the egg) becomes a mystery, a wonder, a promise. To be an egg is to promise discovery. Every egg, from this one (c. 3400bc) to the one you opened into a frying pan this morning, contains and shelters something utterly familiar and utterly unique, something waiting for you to find it. Every egg is a discovery.

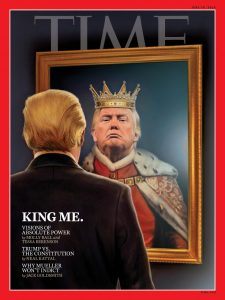

There are certain artists who seem to have something to say about everything and whose work as a result appears regularly in the pages of the journal at which I serve as visual curator. Hieronymus Bosch is one. Caravaggio is another. Paul Klee and William Kentridge make the list. The genius of these artists (and many others) makes their work ever-contemporary, as immediate and compelling today as it was when they made it. The density of their work allows it to absorb the assault of time, so that its meaning can shift and apply itself to any period without diluting the purity of its original conception and execution. Read more »

Little Miracles 2:

Little Miracles 2:

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

A number of scenes in Eugene Zamyatin’s dystopian novel

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The link to Charles McGrath’s ‘No Longer Writing, Philip Roth Still Has Plenty to Say’ which appeared in the New York Times in January, only a few months prior to Roth’s death in May this year, was forwarded to me by a friend who thought I might find the article interesting. How indebted I am to my friend that he thought of me in those terms, for the sending of that article rekindled my acquaintance with Roth; life’s events and circumstances had left my reading of his work to the margins.

The past years have seen many debates about the limits of science. These debates are often phrased in the terminology of scientism, or in the form of a question about the status of the humanities. Scientism is a

The past years have seen many debates about the limits of science. These debates are often phrased in the terminology of scientism, or in the form of a question about the status of the humanities. Scientism is a  The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

The career of Kenneth Widmerpool defined an era of British social and cultural life spanning most of the 20th century. He is fictional – a character in

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car.

It’s a Saturday in May. I’m 17, and I’ve spent the morning washing and waxing my first car, a 1974 Gremlin. I’m so delighted that I drive around the block, windows down, Chuck Mangione playing on the radio. Feels so good, indeed. I’ve successfully negotiated a crucial passage on the road to adulthood, and I’m pleased with myself and my little car. Times change, though, and sometimes even people change. Forty years later, with, I hope, many miles ahead of me, I sold what I expect to be my last car. I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”

I like playing Scrabble, and part of the reason is creating new words. That and the smack talk. I played a game with the swain of the day decades ago, and he challenged my word, which was not in and of itself surprising. As you may recall, if you lose a challenge, you lose a turn. With stakes so stupendously high, you mount a vigorous defense. I ended up losing the battle (and probably won the war) and thought no more of it. The ex-boyfriend brought it up a few years ago; I think he has put that on-the-spot coinage next to a picture of me in his mind. It is a shame that the word he will forever associate with me is “beardful.”