by Brooks Riley

The Alps are much grander this morning. I like to think they tiptoed closer in the night, but it’s only an optical illusion created by a local high-pressure system called föhn, which magnifies them and everything else on the horizon. Sitting outside in the loggia, a spacious recessed balcony that resembles a box at the opera, I am audience to many forms of entertainment—weather theater, rainbow theater, sunrise theater, moonrise theater, but best of all, avian theater with its motley cast of bird species performing their life cycles like variations on a theme, in full view.

The Alps are much grander this morning. I like to think they tiptoed closer in the night, but it’s only an optical illusion created by a local high-pressure system called föhn, which magnifies them and everything else on the horizon. Sitting outside in the loggia, a spacious recessed balcony that resembles a box at the opera, I am audience to many forms of entertainment—weather theater, rainbow theater, sunrise theater, moonrise theater, but best of all, avian theater with its motley cast of bird species performing their life cycles like variations on a theme, in full view.

To really see, sometimes you must simply sit still. You sit still and let it come to you—a thought, an image, a realization, a metaphor, an epiphany, a living creature. High up in a fourth-floor aerie, I see things I never would have noticed in the thick of life when I bustled among my own kind in cities overwhelmingly populated by my own kind. Now I see birds. Watching their performances, I see their consciousness as clearly as I recognize my own. I don’t need to make eye contact to know that they see me too, like actors aware of an audience. It’s an empirical observation but there are stories to back it up. In the great debate over animal consciousness, sometimes less is more, sometimes what you see is what you get, not what you’ve gleaned from neurological mapping or fancy tests. Science and philosophy merely obfuscate the obvious.

Any view can become tiresome over time. The eye begins to explore the details. Up here in the loggia, it is the birds that came into focus, performing center stage on a ladder that runs up the side of a thick chimney across the street. There’s not one bird in the neighborhood who hasn’t perched atop that ladder for whatever reason—ravens, turtle doves, magpies, merles, even a great tit or two. They come with dramaturgy, poignant narratives of survival strategies and competition, of empathy and antagonism, of mutual need and sharing, of joy—the stuff of life no matter what species you belong to. Read more »

When one makes an artwork, something flows from artist to audience. The thing flowing is actually several: concepts, ideas, aesthetic experiences, duration itself, beliefs, attitudes, and probably much more. Artworks work in a similar way to language, although it would be foolish to believe that artworks are language. Their similarities to language end at the transmission from one to another of the things flowing. That’s how language works as well. But for art, as with something like emotion, the flow is vague in how it is sent and received. It seems to me that the best linguistic analogy for what artworks do is located in assertion. Artworks assert a position. Of course it is entirely possible, and even the norm, that their version of assertion is cryptic to the point of being sometimes unintelligible. But assertions don’t need to be crystal clear. One can assert their dominance over another through a series of non-linguistic subtle bodily movements. Likewise, artworks can make assertions through their physical presence.

When one makes an artwork, something flows from artist to audience. The thing flowing is actually several: concepts, ideas, aesthetic experiences, duration itself, beliefs, attitudes, and probably much more. Artworks work in a similar way to language, although it would be foolish to believe that artworks are language. Their similarities to language end at the transmission from one to another of the things flowing. That’s how language works as well. But for art, as with something like emotion, the flow is vague in how it is sent and received. It seems to me that the best linguistic analogy for what artworks do is located in assertion. Artworks assert a position. Of course it is entirely possible, and even the norm, that their version of assertion is cryptic to the point of being sometimes unintelligible. But assertions don’t need to be crystal clear. One can assert their dominance over another through a series of non-linguistic subtle bodily movements. Likewise, artworks can make assertions through their physical presence. Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

Most people see understanding as a fundamental characteristic of intelligence. One of the main critiques directed at AI is that, well, computers may be able to “calculate” and “compute”, but they don’t really “understand”. What, then, is understanding? And is this critique of AI justified?

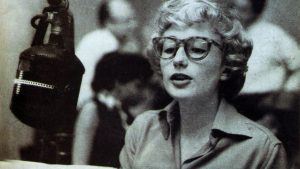

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

Blossom Dearie: incredibly, it was her legal name. The pianist and jazz singer was born Margrethe Blossom Dearie in 1924; all she had to do to get her stage name was to drop the Margrethe. The name perhaps overdetermines the voice. But you’ve got to hear the voice. Light and slim, with little to no vibrato, Dearie’s voice is ingenuous to such a degree that you begin to wonder whether it isn’t, in fact, the least ingenuous thing you have ever heard. It echoes with the four-square court—or was that the tomb? Imagine a sphinx posing her fatal riddle to Oedipus. Then ditch the immortal growl and try hearing, instead, a girl. That’s Dearie, singing her riddles of love and disaster. But unlike the sphinx, she wagers her own life, not other people’s. She knows the stakes, and still, that light, slim voice, with no vibrato, comes floating onto the air.

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature.

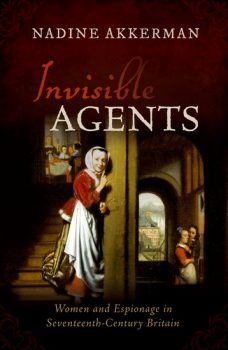

I don’t know how much you know about Petrarch. My guess is that you know him as a poet, primarily for his sonnets. Maybe you associate him with early Italian humanism and its reinvigorated dedication to the wisdom of classical Antiquity. Or perhaps you think of him as someone who expressed transcendental truths about the soul and its searching and wandering nature. History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events.

History has not always been fair to women: their contributions to history have been either marginalised or, not infrequently, unacknowledged. However, the three books, Nadine Akkerman’s (2018) Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth Century Britain, Nan Sloane’s (2018) The Women in the Room: Labour’s Forgotten History, and Cathy Newman’s (2018) Bloody Brilliant Women, are examples of excellent research and scholarship that documents many women’s contributions to historical events. A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

A friend asked me to write a column about Russian cursing a few months ago. I do try to be accommodating, so I looked at several sites to get a better handle on it. In case you were not familiar, cursing in Russian is rich, much more calorically dense than most of what we have in English, except in the rarest cases of accomplished cussers. The problem for me is the translation; it would be so much more gratifying for you to read and imagine the vile torrents of insults than to read a lumpen approximation in English. Therefore, I decided to open up this column to the more universal topic of cursing.

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann)

Step-by-step, breath-by-breath, thought-by-thought, our feet carry us toward our future. (How Things Find Us, Kevin Dann) impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

impermanence, I think anything I buy should last forever. (See this shirt?

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.

Like most people of a certain age, at any one time I have the unfortunate experience of knowing several people, some close, some not, who have cancer. It has become standard for the friend or spouse of the ill person to join one of the many message boards devoted to the subject and post updates to keep their friends and relatives informed. Others use Facebook to share information. Currently there are three people whose lives I follow, mostly from a distance, all with serious forms of cancer, one newly diagnosed but metastasized, two others who have been fighting for months and months.