by Abigail Akavia

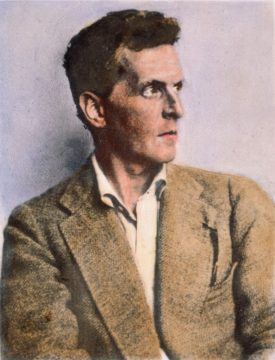

“I was surprised you didn’t start with Philoctetes,” my advisor tells me after my dissertation defense. In our institution, in the crowning moment of a student’s academic career, she is expected not only to publicly display sufficient knowledge in her research field, but also to narrate the ‘making of’ the dissertation topic. Indeed, Sophocles’ Philoctetes could be considered the play that brought me to graduate school to begin with. The dynamics of compassion, suffering, and language in this play are paradigmatic to the questions that shaped my research; a few years out of school, I still can’t (nor want to) get away from this play (and I even wrote about it here once before).

And yet, when presenting the retrospectively made-up timeline of how my research came together, the point where I claimed “it all started” was not Philoctetes, but Sophocles’ most famous play, Oedipus Tyrannus. I did so because I had the opportunity, while in grad school, to direct the play (we’ll call it OT henceforth), an experience that was quite unlike anything else I did as a student, and which was crucial for shaping my academic project. I knew I was interested in the Sophoclean chorus, but only through having to solve for myself the dramaturgical and choreographic ‘problem’ of putting a bunch of seemingly extra bodies onstage who lament Oedipus’ fate did I truly realize how dramatically pregnant this community of vocal witness-bearers is. Working on transforming the script into a performance was a turning point in my engagement with Sophocles, coalescing what I’d learned about his plays and my own interests and hunches about them into a tangible, clear perspective. I came to view the exploration of people’s (in)capacity to be with another person’s pain—or, in other terms, the community’s involvement and reaction to an individual’s tragedy—as one of the driving forces of Sophoclean drama. Read more »

It feels impossible this week not to talk about George Floyd, and yet it feels as if talk has become egregiously cheap, less a mechanism for change than a means of resting in paralyses of complacency, disbelief, or comfort. When rage, grief, frustration, and loss take over communities, states, and entire countries as they have this week, words feel at once like our most important tool and a frantic means of filling what could otherwise be a devastating silence. How do we address a racism so deeply ingrained in society that it feels woven into every fiber of our country’s foundation—and, indeed, was there at the United States’ genesis, when black bodies bolstered a white economy at the expense of their lives, health, and humanity, and in the process built what we so misguidedly call the land of the free, the world’s first great democracy?

It feels impossible this week not to talk about George Floyd, and yet it feels as if talk has become egregiously cheap, less a mechanism for change than a means of resting in paralyses of complacency, disbelief, or comfort. When rage, grief, frustration, and loss take over communities, states, and entire countries as they have this week, words feel at once like our most important tool and a frantic means of filling what could otherwise be a devastating silence. How do we address a racism so deeply ingrained in society that it feels woven into every fiber of our country’s foundation—and, indeed, was there at the United States’ genesis, when black bodies bolstered a white economy at the expense of their lives, health, and humanity, and in the process built what we so misguidedly call the land of the free, the world’s first great democracy? My father had an immensely fat friend whom I often glimpsed filling a plate alone at the buffet table of the King Eddie’s restaurant as I walked past that grand hotel. This man himself had a father even then in those days a nonagenarian, whom he saw daily, devotedly, taking him to the pool for a swim. It turned out that, obesity or no obesity, the friend would outlive my own father by twenty years. Because I liked the man very much, his longevity does not strike me as an injustice. He had a snuffling voice, small but piercing eyes, a gigantic nose and a fund of forgiving affection, the kind dispensed even in the awareness that what was being forgiven might have been awful. He preferred not to know, though his ignorance was (if I may venture a paradox) well informed. My mother played matchmaker for decades in his behalf, possibly because she found him appealing. Her stratagems did not avail. His marvellous acquitting heart remained unpaired.

My father had an immensely fat friend whom I often glimpsed filling a plate alone at the buffet table of the King Eddie’s restaurant as I walked past that grand hotel. This man himself had a father even then in those days a nonagenarian, whom he saw daily, devotedly, taking him to the pool for a swim. It turned out that, obesity or no obesity, the friend would outlive my own father by twenty years. Because I liked the man very much, his longevity does not strike me as an injustice. He had a snuffling voice, small but piercing eyes, a gigantic nose and a fund of forgiving affection, the kind dispensed even in the awareness that what was being forgiven might have been awful. He preferred not to know, though his ignorance was (if I may venture a paradox) well informed. My mother played matchmaker for decades in his behalf, possibly because she found him appealing. Her stratagems did not avail. His marvellous acquitting heart remained unpaired.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point.

There is a statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park. It is tucked in at the intersection of West and Bethesda Drives, massive and unmoving, implacable and forbidding. Despite its size, it goes largely unnoticed, except as a meeting point. I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

I’ve taught shittily these last two months. That’s nothing a teacher ever wants to admit and normally has no excuse for, but these are not normal times.

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that

Two months ago, COVID lockdown was still new; in the US it was horrific that