by Christopher Horner

When the legend becomes fact, print the legend. —The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (dir. John Ford)

No man is a hero to his valet. —proverb

The highest act of reason…is an aesthetic act. —Holderlin (attrib)

Sometimes it seems that growing up and learning things is one long process of disillusionment. Dis-illusion: we shed illusion, fantasy and myth, and so we disenchant the world. Somehow this is both a good and a bad thing. Good, because we cannot, must not, live on lies; bad because we cannot live on facts alone.

There are plenty of people ready to feed us lies, and plenty who want to believe them: about American Exceptionalism, about race, about the economy – about how global warming is nothing to worry about, when in fact it threatens our very lives. We really do need to find out what is happening and and how it came to be. In the UK, for instance, there seems to be the widespread vague sense that the empire was a sort of outdoor relief programme, all about building railways and schools for the lucky natives, and not at all about exploitation and oppression. So who are all these brown skinned people and what have they to do with us? In the USA we have seen the effects of nurturing lies about race and nation, lies that go all the way back to the the founding: the denial of a history of slavery, genocide and subjugation. And our heroes have feet of clay: Gandhi, Wollstonecraft, Lincoln, Churchill, Jefferson, all were flawed. Indeed, the last three in that list can be indicted of racism. And because of their actions, people died.

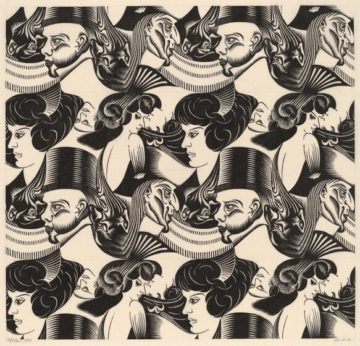

And yet there is more to be said about myth, legend and facts. Sometimes the facts can lead us towards error, and the myth can convey something true, as when an event or person inspires us to reach for something higher and better. Moreover, the desire to debunk and find the dirty laundry can generate its own smell: it can be motivated less by a desire to get at the truth than what Nietzsche called ressentiment: half suppressed feelings of hatred and envy that find a brief satisfaction in bringing down anything noble or good. Sometimes, too, something of the truth is to be grasped in the very illusion it engenders – as Hegel says, appearances both conceal and reveal the essential thing. Let me try to explain with some examples. Read more »

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though. Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.