by Thomas Larson

I want to be an honest man and a good writer. —James Baldwin

1. My affinity for language is a given. But how it was given—and revealed more than other affinities that may have had it out for me as well—is a mystery I’m trying to solve. My hunch is that an affinity for words was present at birth, then snapped-to early on by seductive teachers who assigned adventure narratives and lyric poems, and later the stories of Stephen Crane, the novels of Thomas Hardy, the poetry of Robert Frost and Edna St. Vincent Millay (her marquee name was a poem in itself). The tenderly implied coupling in the woods Tess endured with Alec D’Urberville unfolded so shadily that I had no idea she was being forced against her will otherwise I would have crawled into the novel and run the rapist off in the midst of the act. In such moments, this affinity for the book manifested—a transcendent sense that prose and poetry recognized me as its completion, that I was felt by the writing, meaning that without my moral participation literature was meaningless.

But that wasn’t the well-bottom of my artistic predilection. The inner beacon that called me to be a reader and eventually a writer was also calling me to play music. The entwining of writing and music commingles linear sense and sounded shape, to me, nothing surprising. Which is to say there’s an overlap, an equivalency, and a separation with which these two similarly spirited and self-assertive arts run together in my blood. My artistic sensibility was tuned to language; but some rapacious gnome within, also stirred in childhood, kept using music to mystify and impugn my word bent and its stays, the rebel cause to desacralize my confidence, my expressive facility, my destiny (even in an essay like this).

After all, on the music road, at age eight I first heard a Methodist church choir and I badgered my mother to go for a tryout, which I did and got in; at fourteen, because I saw Benny Goodman swing with a quartet on TV, I took up the clarinet and went right into junior high band; in high school, I was a self-taught guitarist, songwriter, and leader of a Dylanesque folk-rock group; at thirty-three, I earned a bachelor’s degree in music composition, my senior thesis, a knockoff of Morton Feldman’s “Rothko Chapel”; finally, on the strength of a performance art-piece for pianist, electronics, and theater, “Kandinsky’s ‘Several Circles,’” I entered the Ph.D program in avant-garde composition at the University of California, San Diego. Along the journey my synchronous affinities for writing and music developed concurrently, journal writer and piano student, hand-in-hand, double fallbacks, fraternal twins. Read more »

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

Of all the secondary discomforts imposed by the pandemic, the most treacherous may be inertia. Life, interrupted, can be characterized as an absence of movement, like a stream that stops running, stagnating as the surface begins to cloud with algae and other still-standing detritus. Inertia that stems from the current situation can quelch any creative impulse. Even cinema, that paradigm of life in motion—the moving picture—isn’t much help if we expect our own lives to keep moving as well as movies do. They don’t, at least not right now.

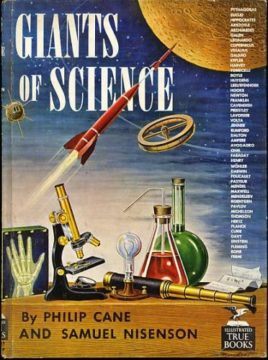

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

In many ways, the story of my life is the story of books that I have read and loved. Books haven’t just shaped and dictated what I know and think about the world but they have been an emotional anchor, as rock solid as a real ship’s anchor in stormy seas. As the son of two professors with a voracious appetite for reading, it was entirely unsurprising that I acquired a love of reading and knowledge very early on. The Indian city of Pune that I grew up in was sometimes referred to as the “Oxford of the East” for its emphasis on education, museums and libraries, so a love of learning came easy when you grew up there. For 35 years until their mandatory retirement, my parents both taught at Fergusson College in Pune.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though.

At the 100th anniversary of John Rawls’ birth back in February, some of the most generous op-eds, whilst celebrating the brilliance of his thought, lamented the torpor of his impact. ‘Rawls studies’ are by no means the totality of political philosophy, but they are one of its most significant strands, and his approach has been dominant for the past 50 years. I’m an admirer of political philosophy, having happily spent much time and energy studying it, specifically looking at theories of deliberative democracy, an area with important connections to Rawls’ thought. That political philosophy does not have much to say that is of direct practical concern does not bother me, the sense that it is not just uninfluential, but is disconnected from the reality of the present moment does though. Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

Anderson Ambroise. Rubble Sculpture.

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

I don’t think I saw an actual daffodil until I was 19, although I had admired the many varieties I saw pictured in bulb catalogs and even—I hesitate to admit this—written haiku about daffodils (at 14, in an English class). When my first husband and I drove through Independence, Missouri, early in our marriage, I saw my first daffodils, a large clump tossing their heads in a sunshiny breeze. Wordsworth flashed upon my inner ear, and as I remember it, I recited “And then my heart with pleasure fills, and dances with the daffodils!” (If I did in fact say that, I’m sure I added the gratuitous exclamation point.) My husband, who was driving, gently asked me to return my attention to the map (I was navigating).

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.

In 1887 Ludwik Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and amateur linguist, published in Warsaw a small volume entitled Unua Libro. Its aim was to introduce his newly invented language, in which ‘Unua Libro’ means ‘First Book.’ Zamenhof used the pseudonym ‘Doktor Esperanto’ and the language took its name from this word, which means ‘one who hopes.’ The picture shows Zamenhof (front row) at the First International Esperanto Congress in Boulogne in 1905.