by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Earlier this week, European investigators concluded that the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny had been killed with epibatidine, a toxin unknown in Russia’s natural environment and ordinarily found only in the skin of small, brilliantly colored frogs native to the rainforests of South America. If that conclusion is correct, a molecule shaped in one of the most intricate ecosystems on Earth has completed a journey that ends not in the forest, nor in the laboratory, but in a prison cell. For Putin’s Russia, this is one more marker on the road to political assassination using chemical and biological weapons.

Long before laboratories named it, indigenous communities of the Amazon understood through long experience that certain tiny, extraordinarily bright and beautiful frogs carried extraordinary power in their skin. The knowledge was practical and restrained. It served hunting, survival, and continuity. It was part of a relationship with the living forest in which danger and respect were inseparable. Nothing in that knowledge pointed toward geopolitics or assassination. The molecule existed only within a web of life that had shaped it.

Centuries later, science encountered the same substance and read it differently. At the National Institutes of Health, the chemist John Daly devoted decades to the study of amphibian alkaloids, following faint chemical traces through repeated expeditions, careful collections, and patient analysis. His work was not driven by persistence, by the belief that small natural molecules could reveal deep biological truths. From thousands of specimens and years of attention emerged epibatidine, a molecule isolated from the skin of a poison dart frog endemic to Ecuador and Peru: a structure modest in size yet immense in biological effect, binding human receptors with an affinity evolution had refined without intention. Daly turned into something of a folk hero whose findings resonated beyond the halls of chemistry. Paul Simon even memorialized epibatidine in his song, “Senorita with a Necklace of Tears”:

Nothing but good news

There is a frog in South America

Whose venom is a cure

For all the suffering that mankind must endure

More powerful than morphine

And soothing as the rain

A frog in South America

Has the antidote for pain.

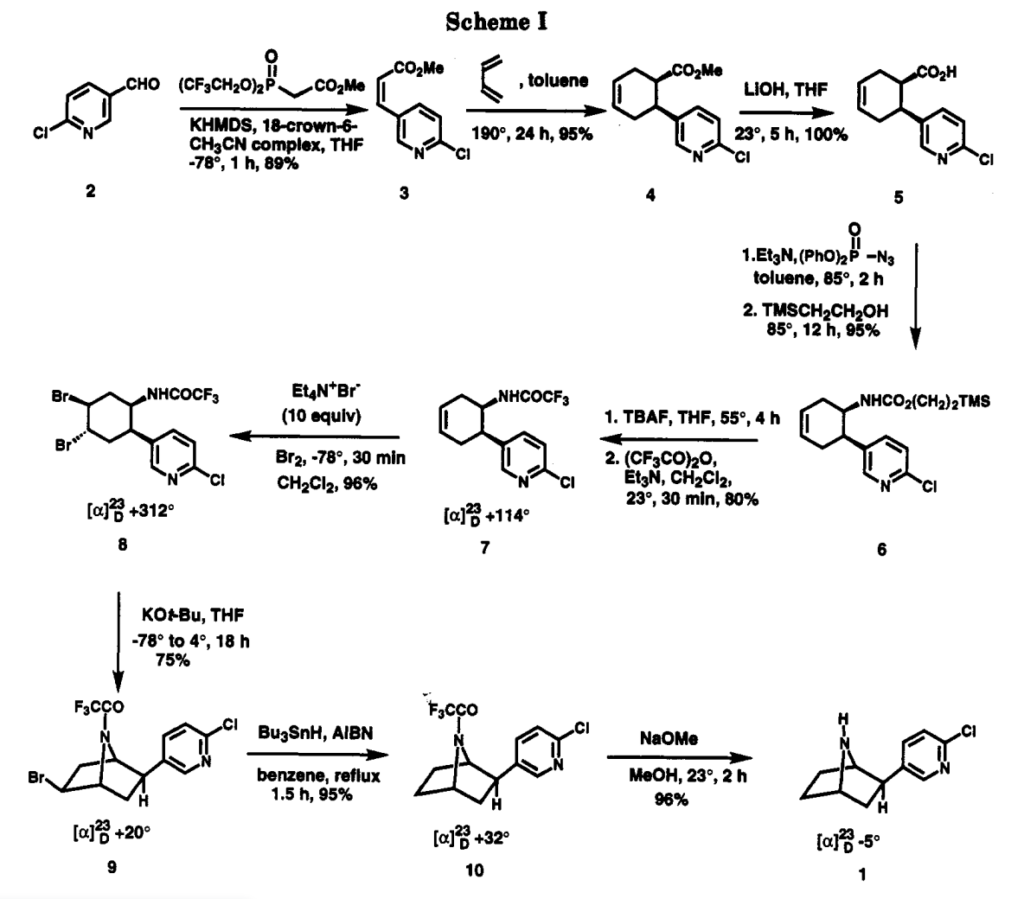

Chemists soon learned to divine the knowledge of the forest away from it. Through complex, multi-step synthesis, most notably in the 1993 work of Harvard chemist E. J. Corey and his collaborators, epibatidine passed fully into human knowledge. In a tradition that has been perfected by chemists to the level of a fine art, rare, exotic naturally occurring compounds no longer need be harvested from fragile ecosystems but can be synthesized from scratch, from cheap, easily available molecules. Epibatidine’s compact geometry, rigid form, and precise interaction with biological receptors revealed how a very small molecule could exert overwhelming physiological force. Based on its mechanism of action, pharmacologists imagined powerful, non-addictive, non-opioid analgesics for severe pain.

But biology is indifferent to hope. The same precision that made the molecule promising made it dangerous. Toxicity narrowed the distance between remedy and harm until the therapeutic path closed. Corey’s own paper contains a small but haunting observation, easy to overlook amid the triumph of synthesis. Reflecting on laboratory exposure, the authors noted:

Unfortunately, toxicity can be detected at ca. five-fold higher concentration. We have noticed that exposure to very low levels of 1 and the enantiomer (for example when eluting a few mg from a TLC plate) in ambient air caused nasal irritation and congestion in both students and researchers who have worked with these substances.

The sentence is clinical and typical of the language of science, almost understated, yet it reveals something profound. Even in the controlled calm of an academic laboratory, far from politics or violence, the molecule’s power announced itself. The boundary between intellectual beauty and biological danger was already present, quietly, in the air above a chromatography plate. Epibatidine’s toxicity is extraordinarily high, higher in fact than cyanide; only other favorite Russian instruments of assassination, poisons like ricin or VX, approach its LD50 (the dose at which fifty percent of a sample of test animals dies).

The medical promise receded, but the knowledge remained. And in the modern world, knowledge travels farther than forests. A molecular structure once published is no longer local. A synthesis once achieved cannot be confined. While epibatidine proved too toxic for therapeutic use, it proved to be a potent tool for pharmacologists to study pain pathways. Corey’s synthesis, and those of others, made possible the commodification of the molecule so that it’s now available from any number of chemical vendors who can sell it to qualified laboratories.

But a molecule shaped by evolution, noticed by indigenous hunters, pursued by patient scientists, and admired by creative chemists may now have entered the machinery of state violence. To those who ask why the state might have used such an exotic poison, at least one explanation can be simply stated – standard toxicity screens would not detect a substance that has not been used to perfect the art of killing before.

But if the conclusions about Navalny’s death are sustained by evidence, epibatidine’s path will mark a characteristically unsettling trajectory in the history of modern science. At the risk of oversimplification it can be stated pithily: From beauty; to knowledge; to ingenuity; to hope; to death and woe. No step intended the next, yet together they form a coherent and troubling history. Within this single molecule now reside three truths: the memory of forests and native wisdom, the achievement of science, and the reality of human suffering. None erases the others. All persist.

Chemistry itself remains indifferent. Atoms obey physical law, not moral judgment. Meaning arises only in the uses to which knowledge is put. Modern history has repeatedly shown how the same understanding can yield both healing and destruction – fertilizers and explosives, energy and annihilation, medicines and poisons emerging from identical principles. If epibatidine has entered political violence, it joins a lineage in which scientific brilliance and human cruelty coexist without contradiction.

For those who endure loss, such reflections provide little comfort. Grief does not admit molecular explanation. Yet to the chemist, epibatidine’s structure remains what it has always been: precise, elegant, and intellectually compelling. Here lies an unease seldom spoken aloud – the recognition of what might be called the terrible beauty of science. A chemist will always have to sustain the uneasy paradox that substances which he or she finds beautiful can be put to the most terrible use. But to perceive elegance in a toxic molecule is not to excuse its use. It is to acknowledge that the patterns revealed by nature exist independent of human intention. The same understanding that illuminates a toxin also makes possible the design of medicines. To turn away from that understanding would not undo harm; it would only diminish the knowledge through which suffering might someday be relieved.

The terrible beauty of chemistry is the terrible burden of knowledge itself. For the scientist must live with a realization that cannot be set aside: discoveries pursued in curiosity, discipline, and the hope of alleviating human suffering may, in other hands, become instruments of harm. Knowledge once revealed cannot be recalled, and intention offers no protection against misuse. The history of science has made this truth unavoidable. What is learned in the service of life may be turned, without warning, toward death. Scientific understanding is morally agnostic. It carries within it no command for mercy and no prohibition against cruelty. Those who extend its reach must therefore bear a responsibility unlike that of most other professions: the responsibility of seeing clearly what their work makes possible, even when they cannot control how that possibility is used. As the physicist Freeman Dyson once simply stated, “We are human beings first and scientists second, because knowledge implies responsibility.”

A humane society must hold both truths at once: the illumination provided by science and the suffering that misused knowledge can bring. Chemistry reveals what is possible. What follows remains, as it always has been, a human choice. And in that choice, made again and again across generations, lies the distance between the beauty of a living forest and a voice silenced in a prison cell.