by Rafaël Newman

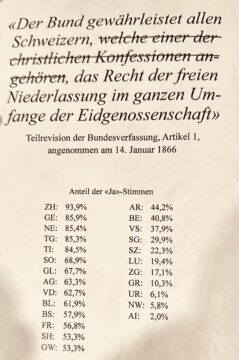

One hundred and sixty years ago this month, in a national referendum held on January 14, 1866, Jews were given the official right to reside throughout Switzerland. Jewish people, whether of foreign provenance or Swiss-born and already living on Swiss territory, had been explicitly forbidden to establish residency in Switzerland in its constitution of 1848, the year modern Switzerland was founded. Since the Middle Ages, when they were re-admitted following the pogroms and expulsions of the 14th century, such permanent domicile as was permitted to Jews among the Swiss had been confined to the two villages of Endingen and Lengnau, in the canton of Argovia. It was only under economic pressure from its main trading partners, the US and France, which threatened the young state with punitive tariffs, that Switzerland—in the form of contemporary Swiss suffrage: in other words, exclusively Christian men—agreed to make the change. Even so, rates of approval in 1866 were drastically unequal across the country, with 93.9% of voters in the populous canton of Zurich favoring Jewish residency, and the tiny, remote half-canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden, which would continue to deny women, whether Christian or otherwise, the right to vote until the late 20th century, rejecting the measure by 98%.

Seventy-five years later, with World War encroaching on its frontiers, the Swiss establishment saw this enforced tolerance tested anew, as Jews fled the Third Reich for asylum within Switzerland’s neutral borders. Although they accepted some of these refugees, Swiss officials notoriously sent many back, their passports marked with a “J”, and placed restrictions on the professional and political activities of those they did admit (such as the poet and philosopher Margarete Susman, on whom see here and here), both to protect “native” Swiss from competition, and to avoid provoking the Nazi authorities, with whom clandestine relations were being maintained.

Nevertheless, in January 1941, a group of Jewish residents in Zurich, several foreign-born, was able to join the musician Marko Rothmüller in founding Omanut, an association for the promotion of Jewish art. The Swiss organization was created in memory of the original Omanut, which Rothmüller, a Yugoslav immigrant, had founded in 1935 in Zagreb, but which had since vanished under the Nazi occupation of Croatia.

I first heard of Omanut in 1998, in Zurich, when I met Nina Zafran-Sagal, the daughter of Vladimir Sagal, one of the founders of the Swiss Omanut in 1941, who would herself go on to serve as the association’s president for a decade, from 2001 to 2011. I had come to Zurich from Berlin, where I had participated in a DAAD Summer Seminar for postdocs at the Einstein Forum. Sander Gilman, the leader of the course, was at the time the general editor of a series of books devoted to the contemporary Jewish literature of various countries. The series, published by the University of Nebraska Press, already comprised annotated anthologies of writing by Jews in Austria, Germany, South Africa, and the UK. When Sander asked me to edit the Swiss volume, I said yes, with equal measures pleasure and trepidation.

Gilman’s brief was simple: identify a collection of living Swiss-Jewish writers, assemble excerpts from their literary work in English translation, and write an introduction, setting the texts in historical and literary-critical context. My work on the project proved a little more complicated, since, until I moved to Switzerland, I had only known vaguely of Elias Canetti and Albert Cohen as writers with Swiss and Jewish affiliations—and they were both deceased. So I would be obliged to scout out these putative Swiss-Jewish authors myself, somehow, without aimlessly (and ominously) asking Swiss writers I met whether they also happened to be Jewish.

Hence my interview, in the fall of 1998, with Nina Zafran, recommended to me as a likely informant. And indeed, Nina—who maintained that Switzerland was the only country in the world where Germanophone Jews could in good conscience still speak their native language—was able to direct me to a number of Swiss-Jewish authors of her acquaintance. I went on to assemble 18 such writers, among them Jean-Luc Benoziglio, Luc Bondy, Sergueï Hazanov, Gabriele Markus, and Stina Werenfels, and to present my translations of their work (from the German and the French) alongside my critical assessment of “Jewish literature” in the Swiss context.

Hence my interview, in the fall of 1998, with Nina Zafran, recommended to me as a likely informant. And indeed, Nina—who maintained that Switzerland was the only country in the world where Germanophone Jews could in good conscience still speak their native language—was able to direct me to a number of Swiss-Jewish authors of her acquaintance. I went on to assemble 18 such writers, among them Jean-Luc Benoziglio, Luc Bondy, Sergueï Hazanov, Gabriele Markus, and Stina Werenfels, and to present my translations of their work (from the German and the French) alongside my critical assessment of “Jewish literature” in the Swiss context.

In addition to the volume in the UNP series, I also published a German-language version of the book, with translations of the French excerpts, and of my own contribution, by Inge Leipold. That work was supported by the Schweizerischer Schriftstellerverein (SSV), one of the two Swiss writers’ unions in operation at the time. In 2001 the SSV was in the process of reorganizing itself and uniting with Gruppe Olten, its rival association, and was keen to use our co-publication as a token of remorse for its collaboration with the Swiss authorities during the period of the Third Reich, and for its connivance in making life difficult for those few Jewish writers who were granted refuge in Switzerland.

The German-language volume, published by Limmat Verlag in Zurich, appeared as Zweifache Eigenheit, or “double singularity”. My title for the Swiss edition was a reference to remarks made by Hermann Levin Goldschmidt, the German-born Jewish philosopher who lived in Zurich from 1938 until his death in 1998 and who served as president of Omanut from 1948 to 1956. During that period, in 1954, Goldschmidt assessed the status of Swiss Jews thus:

We find ourselves in a special relation to the rest of the world’s Jewry, a relation defined by our Swiss situation; but we find ourselves also in a special relation to the other population groups of Switzerland: that of the Jewish segment of the Swiss population. It is only on the basis of this double singularity [zweifache Eigenheit] that questions of Jewish cultural activity in Switzerland can be correctly addressed—that is, we must determine our actual problems, and we must emphasize our particular accomplishments.

In the aftermath of the Shoah, being both Jewish and Swiss meant that Goldschmidt’s compatriots were distinguished by a twofold peculiarity: set apart from the majority culture into which they had been integrated, under duress, less than a century before, they were also set apart from the world community by virtue of their citizenship in a country that had been spared the recent conflagration, and whose existence had for some time already been predicated on the Great Powers’ need for a “neutral” buffer zone in which to transact their business, whether commercial or political.

A general reckoning with official Switzerland’s role in the 20th century’s disasters, and with its ambivalent attitude to its Jewish citizens, was not yet possible in the immediate postwar period. But during my research on the anthology, from 1998 into the new millennium, times had changed, and I pursued my work during an upheaval in Swiss-Jewish affairs. Switzerland had been under pressure from the World Jewish Congress (WJC) since 1996 to come clean about the massive involvement of its banking establishment with the Nazis, charged with purchasing gold looted from Jewish victims as well as with retaining so-called “dormant” accounts belonging to Jews murdered by the Nazis. Among the people I interviewed for my project was Daniel Wildmann, a young Swiss-Jewish historian who was working with the Bergier Commission, established by the Swiss government to respond to the WJC’s charges, and who also served, with Stina Werenfels, as a member of the board at Omanut.

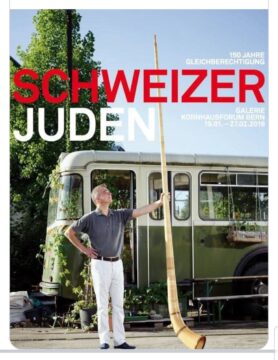

My association with Omanut, which thus began during this ferment as a tangential connection, but which taught me a great deal about the complex relations between Jews and Switzerland, has been strengthened over the past quarter century. In the years since my first meeting with Nina Zafran in 1998 I have taken part in many Omanut events, whether as audience member or participant. In 2007 I contributed to Ein gewisses jüdisches Etwas (A certain Jewish something), an exhibition at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich organized by Michael Guggenheimer and Katharina Holländer under the aegis of Omanut; in 2010 I moderated an appearance by Daniel Mendelsohn, who presented The Lost:A Search for Six of Six Million, his family memoir of the Shoah, by invitation of Omanut; in 2015 I was asked by Omanut to moderate a panel, featuring Anne-Marie Kenessey, Gabriele Markus, and Sergueï Hazanov, to launch a new issue of the journal orte devoted to Jewish literature in Switzerland; in 2018 I delivered a presentation entitled “Hegel, Schlegel, Bagel,” on the social history of the renowned Jewish bakery product, as part of the Woche der jüdischen Kultur Zürich festival organized by Omanut; in 2023 I read poetry and prose texts and participated in a podium discussion of polyglot literature at Omanut’s Lesefest zum mehrsprachigen Schreiben; and, just this past weekend, I attended the premiere, co-hosted by Omanut, of Hirschfeld—Unbekannter Bekannter, a film by Stina Werenfels and Samir about the career of Kurt Hirschfeld, the theater director who was among the generation of Jewish refugees from the Shoah, who made Zurich into a center of culture in the 1940s and into the postwar period, and who was an early collaborator with Omanut as it had been reborn in Switzerland.

This month, of course, Omanut also celebrated its 85th anniversary, with a day-long event held at the Beijz, since 2024 the association’s headquarters in a former restaurant in Zurich’s Seefeld neighborhood. The name of the clubhouse is a clever reminder of the ancient interaction of Jewish culture with the Swiss quotidian: The Yiddish word beijz, from the Hebrew בַּיִת (bayit), meaning an inn or restaurant, has found its way into various southern German dialects, including the Swiss varieties, where it has become the standard term for a humble place to eat and drink, unremarked by speakers of Schwyzerdütsch as a “foreign” loan word.

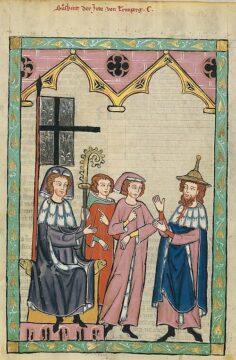

But just how foreign can Jewish culture be to Switzerland anyway? Jews have lived on Swiss territory, albeit with significant and painful interruptions, since Roman times. The Codex Manesse, a canonical manuscript of medieval German song collected in 14th-century Zurich, features contributions by Süsskind von Trimberg, who may have been a Jewish troubadour. “Joggeli wott go Birli schüttle,” a popular Swiss nursery rhyme, was likely inspired by “Chad gadya,” the song with which Passover services often close. Kurt Guggenheim (1896-1983), for whom a central Zurich street is named, was the Swiss-Jewish author of Alles in allem, a seminal chronicle of life in Switzerland during the first half of the 20th century. Lazar Wechsler (1896-1981), a Russian-born Jewish immigrant to Zurich and the founder of Praesens-Film in 1924, produced some of the best-known examples of Swiss cinematic folklore. Ruth Dreifuss, a Swiss Jew from St Gallen, resident in Geneva and with roots in the Argovian villages of Endingen and Lengnau, has served as president of the Confederation. And when, this past January 11, I attended “Visions of Tomorrow,” the brainstorming event organized by Karen Roth, Omanut’s current, exceptionally active president, to celebrate the 85th anniversary of the Swiss association’s founding, I was surrounded at the Beijz by what looked and sounded like a group of Swiss burghers—who just happened to be Jewish.

Of course, among the items on the agenda that day was a quintessentially Jewish issue: or rather, a quintessentially Jewish issue in its Swiss form. For the Beijz, the cozy little restaurant in which we were assembled that day, is available to Omanut—in a fashion typical of Zurich, where a speculation and building boom has been underway for some time—only temporarily, as its provisional home, while the valuable inner-city property awaits rezoning and development. In other words, Omanut, Switzerland’s association for the promotion of Jewish art and culture for the past 85 years, founded in the same month, three-quarters of a century later, as the 1866 referendum granting Jews the right to settle permanently on Swiss territory, will soon be obliged to up stakes and seek a new residence.

What makes this next phase in Omanut’s existence quintessentially Swiss is its replication of the very conditions of Switzerland’s national identity. Switzerland, a confederation of linguistic regions, is, in 19th-century terms, a Willensnation, not a Kulturnation: the product of rational design, rather than ethno-nationalist sentiment; a political corporation formed by commercial interests, rather than by tribal affections; a microcosmic, multinational conglomerate, rather than a nation-state. It is inordinately dependent on its place, situated as it is at the vital but challenging Alpine crossroads between north (the Germanic world) and south (the Roman world), and thus able to control the passes (both transmontane and subterranean). It is valuable to the culturally hegemonic, militarily powerful, resource-rich world around it for its strategic utility as a trans-shipment center (Umschlagplatz) for goods and people. It owes its existence, more than most other “nations,” to its location—and is thus especially hostile to interlopers and would-be foreign residents, despite (or perhaps precisely due to) the fact that it serves as a site of transit, through which strangers are by necessity forever passing.

All of this has made life peculiarly difficult for Jews on Swiss territory, susceptible as they have been to the suspicions of the settled population, which has been affronted by their mobility and apparent rootlessness, and which has reified those suspicions by refusing them the right to settle, and then, once they had been obliged, by economic circumstances, to permit their settlement, by restricting their activities.

Yuri Slezkine, in The Jewish Century, an eccentric history of modernity, identifies an anthropological category he calls “service nomads,” small and distinct socio-ethnic groups that live among larger cultures and perform clearly defined roles and rituals. These groups Slezkine terms “Mercurians,” for their emulation of Hermes, with the Greek god’s penchant for communication, trade, and trickery; and he details how they are both integrated into the general “Appolonian” societal system—the majority population of settled food-producers, peasants, and warriors—while remaining self-consciously separate from it. Slezkine examines a broad array of such groups around the world, including the Parsis of India, the Lebanese of Latin America, and the Chinese of Southeast Asia. The two “Mercurian” populations he returns to most often, however, and who emerge as paradigmatic of the phenomenon his book describes, are the various Roma and Sinti peoples, whom he refers to as “Gypsies,” and of course the Jews.

In addition to Jews, Switzerland has also been familiar with the other paradigmatic type of “service nomad”—the Yenish, or Fahrende (“travelers,” the Swiss-German term for all “vagrants,” including Roma and Sinti), who live on Swiss territory and who may be a branch of the Romani peoples—and it has, over the course of its history, attempted to deal with the two groups in two different, opposed fashions. In the case of the Fahrende, the Appolonian Swiss tried to manage that group of Mercurians through enforced assimilation, with a notorious campaign of kidnapping known as Kinder der Landstrasse (Children of the Road), which from 1926 until 1973 took Yenish children away from their families and placed them in foster homes, while institutionalizing their parents. As for Jews, who in distinction to the “travelers” had a clearly stated desire to settle among the majority population, the opposite tactic was necessary for the hygienic preservation of the Appolonian “blood and soil”: expulsion.

But Slezkine’s global grand theory has a crucial second movement, for which his identification of various Appolonian and Mercurian societies, and the tensions between them, over a longue durée is the preparation. “Modernity”, he writes, “was about everyone becoming a service nomad: mobile, clever, articulate, occupationally flexible, and good at being a stranger.” The transformation, over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, of empires into national states, the replacement of religion by language and culture as the chief determinant of national belonging, the process of industrialization and the concomitant migration of settled, food-producing populations from the land to an urban labor context, as well as, importantly, the rise of globalization—all of this has required European Appolonians to adapt in a new way: by means of neither assimilation nor expulsion of their Mercurians, but by emulation of them. Or rather, by emulation of the most vitally useful, most egregiously other group of Mercurians, a group that was, however, also the most uncannily familiar to European Christians, since their religion, still culturally central if now on the wane, was manifestly an outgrowth of Judaism. As Europeans have been “painfully transformed” into Jews during the modern period, Slezkine maintains, the Jews themselves have emerged “from legal, ritual, and social seclusion” to join the ranks of the various majority populations among whom they have already been living for generations. Now as full-fledged members, however uneasily, and repeatedly required to declare their allegiance to the new national culture and forever under latent suspicion of ulterior loyalties.

Such a transformation is strikingly obvious in Swiss modernity, as anomalous as Switzerland’s particular form of statehood may be in the European context. Although the Swiss long ago declared their independence from the empires surrounding them, their “nation” has famously differed from the ethno-national entities that have grown up around it in the early modern period, and from which it has, by choice or obligation, remained aloof. Now, however, over the course of the past century and a half, Switzerland, which had until recently been an exporter of its “human resources,” has transformed a predominantly agricultural economy into a thoroughly modern member of the present global capitalist regime, offering services based on information (financial, medical, pharmaceutical, technological), which Slezkine identifies as historically Mercurian, and becoming a net importer of a wide range of foreigners eager to share in the lucrative Swiss brand of modern “Jewishness”.

Thus, as Switzerland’s geographical location becomes less relevant, in an increasingly dematerialized, digitalized, globalized world economy, so too has it become easier for it to accommodate the “others” who have long constituted the vanguard of the Mercurian, networked mobility to which Appolonians (must) now aspire. Of course, there is still a virulent strain of anti-immigrant xenophobia current in Swiss politics, just as there is, mutatis mutandis, in the politics of the Jewish ethno-nationalist state: but both of these baleful developments are part of another, if related chapter in the history of liberal capitalism.

In the midst of this evolution, Swiss Jews continue to search for a way to preserve their cultural heritage while remaining fully integrated into the larger, non-Jewish, but by no means still entirely Christian society of Switzerland. And as the once nomadic Omanut celebrates its 85th birthday, and begins the search for a new “home” in Switzerland, perhaps it can help the country at large recognize, not the double singularity of its Jewish citizens, but its own singular duality: as an ancient nation with a thoroughly modern constitution; a geographically crucial, settled location, at least one-quarter of whose population is comprised of immigrants; a mixture of Appolonian and Mercurian traits and skills.

In La Réserve des Suisses morts (The Reserve of Dead Swiss), Christian Boltanski (1944-2021) drew a connection between Switzerland, whose population at the time the French-Jewish artist created the work, in 1990, was roughly six million, the canonical number of Jews murdered by the Third Reich. The piece, which comprises photographs, mounted on stands and boxes, of recently deceased Swiss people taken from the obituary section of a small cantonal newspaper, thus constitutes an oblique meditation on the Shoah, as well as a statement regarding the arbitrary nature of human ethnic divisions and animosities. In an interview about La Réserve, Boltanski implicitly cites the famous Weimar-era joke about the two antisemitic motorists stalled in traffic: One exclaims in outrage, “All of our problems are caused by the Jews and the bicycle riders!” To which the second responds, “But why the bicycle riders?!” Boltanski’s remark foregrounds the ostensible naturalness of a central presence in the European narrative for the Jews, whether as villains or as victims, by replacing them with another, apparently “neutral” population: “Working on dead Swiss people,” Boltanski noted, “elicits the question: ‘Why the Swiss?’ That’s what interests me. The Swiss also die, because they are human.”

_____________________________________________

I have profited greatly in my research from Katarina Holländer, DIE FRAGE NACH DER JÜDISCHEN KUNST: 60 Jahre «OMANUT, Verein zur Förderung jüdischer Kunst in der Schweiz» (Jüdische Rundschau: Zurich, 2001).