by David Kordahl

Peter Morgan has worked for decades to appreciate the underlying structures of physics. But can he convince others he is right?

When I receive unsolicited scientific communication, I bin writers into two crude categories: Possible Collaborators, and Probable Crackpots. Of course, these categories may overlap. Ted Kaczynski, after all, taught at Berkeley before he made those bombs.

When I first received a message from Peter Morgan, I wasn’t sure where to slot him. The fact that he was listed as a lab associate for the Yale University Physics Department pushed the needle of my prior judgment toward Collaborator. But the fact that he was cultivating journalists to promote his ideas about quantum theory…well, that swung my needle far the other way.

Morgan first contacted me on X.com (the website formerly known as Twitter) on December 9, 2024. I had posted the review of Escape From Shadow Physics: The Quest to End the Dark Ages of Quantum Theory that I had written for 3 Quarks Daily, and he posted a short comment in response. Seeing Morgan’s frequent physics posts, I followed him. Minutes later, he pitched me a column idea.

Morgan suggested that I write about his ideas:

I hope that if there are any of the ideas that deserve to go viral, they will do so sooner rather than later, then I can admire what better mathematicians and physicists than I am can do with whatever survives the winnowing. There are quite a few people who react positively to how different this is (for one thing it’s not a ToE, and the data and signal analysis aspect is met almost joyfully by some people), but I’m so far out in left field that nobody quite believes that I’m not making some obvious mistake. It’s always embarrassing to be the person who champions nonsense, right?

Right. I went to Morgan’s profile and watched one of the talks on his YouTube channel. After realizing I had no immediate way of assessing whether there was any there there, I sent him a polite but noncommittal reply, and placed a mental bookmark, thinking I might contact him again once I had time to spare.

I contacted Morgan again on June 3, 2025, after attempting to read some of his papers. What drew me back in was his promotion of “CM+,” a version of classical mechanics that, by adding additional structure, would accommodate outcomes typically called “non-classical” by people interested in quantum theory.

Before we first spoke, we exchanged messages back and forth on X. It was apparent that we shared at least some common readings. He sent me a talk he had recently given virtually to a group of students in Bangladesh. When we made plans to chat over Zoom, he prepared by commenting on several pieces I have posted on 3QD. He was unfailingly polite, but sometimes critical:

I’m not getting at you when I quote these two sentences from your [2022 essay, “What Entanglement Doesn’t Imply”]: “The important thing to understand about entangled particles is how they became entangled. Particles become entangled when they interact.” At least, I hope you won’t be offended. I suggest this beginning of a field and events alternative: “The important thing to understand about entangled events is that they cannot be straightforwardly attributed to a pair of ordinary particles. Instead, we can think of the events happening as they do because we have engineered a modulation of all the details of the noisy electromagnetic field that is contained by an experimental apparatus to be just so. It’s not easy to make it happen and to be sure that it’s happening, but it can be done and when it is done we can talk about a pair of ‘quantum particles’ as a concise way to say that ‘the noisy electromagnetic field is just so’.”

The first time we spoke, over Zoom, was on June 9. My opening question was whether Morgan considered himself physicist, or a math guy, or a philosopher of physics, or what. This was met diplomatically with the response that those who work in foundations of physics need to cross boundaries between the three, from math to physics to philosophy—but his last three publications have him primarily giving talks to physics departments, so he now calls himself a physicist.

Peter Morgan is an Englishman in his late 60s who has lived much of his life near international academic hubs. This puts me on guard—I take a perverse pride in having never set foot in any part of the Ivy League—but an unusual background has always positioned him just outside the center of action. After earning an undergrad math degree from Oxford, Morgan spent twelve years as a computer programmer before he “dropped out hard” from that career. He spent time teaching math, then selling home electronics. He had some acquaintance with physics from his math studies and his own reading, and he eventually ended up at Durham University, where he got an M.S. in Particle Physics…and met his wife.

Morgan’s wife is not just a footnote to the story. She is a successful classics scholar, and he became the trailing spouse, following his wife as she was appointed at University College London, then at Oxford, then at Yale, where they have remained since 2004. His employment has been spotty, ranging from grocery shelf-stocker to stay-at-home dad, but his proximity to world-class physics and philosophy departments has given him access to many leading lights.

This made talking with Morgan entertaining, as he had anecdotes about many figures who I had only read, and he had read many figures I’d never even heard of. But when we discussed CM+, I found myself confused.

The Morgan paper I most wanted to understand was “An Algebraic Approach to Koopman Classical Mechanics,” where he debuted the CM+ framework. Unfortunately, I was not in a great position to understand this. The Koopman-von Neumann formulation of classical mechanics was just one of the things I’d never heard of before Morgan recommended it to me. In the early 1930s, Bernard Koopman and John von Neumann published the first paper showing how classical mechanics can be put into the language of quantum theory—in the language, that is, of complex numbers, operators, and wavefunctions. This is not “new physics” so much as it is a reiteration of old physics in a slick new idiom, allowing classical and quantum descriptions to share a similar mathematical framework.

I had to beg off the first talk early to take care of my kids, but I said I would think about something in all this that could be written about for a non-technical outlet like 3QD. Not long afterward, Peter Morgan sent me an email:

I’ve been trying to think of a slightly provocative title and hook. One possibility might be to point out that although stochastic processes have become quite popular recently (Barandes, Carcassi, Oldofredi, Khrennikov, Wetterich, …, and, much earlier, since the 60s, there have been Stochastic ElectroDynamics, Nelson, …), they haven’t convinced physicists.

I didn’t recognize the names he had listed, so this seemed like a dead end. Over email, we agreed to chat again the next week. I would have my work cut out for me just trying to make sense of his particular point of view. By the time we talked again on June 17, I had spent time combing through his publications. By the end of the conversation, I had a better idea about what he was trying to achieve.

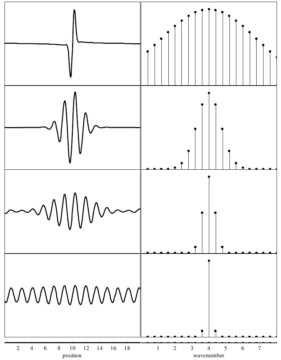

To understand Morgan’s approach, I needed to start with the basics. What makes quantum physics different from classical physics? To answer this, physicists often point to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle—the idea that the more precisely you know a quantum object’s position, the less precisely you can know its momentum, and vice versa. But another way to look at this is that position and momentum in quantum theory are non-commutative—which has a mathematical definition, but for the purposes of this discussion, roughly means that the order of various measurements is important. Another way to say this is that there’s something incompatible about questions we might ask about non-commuting variables.

This brings us to Morgan’s central insight. Quantum non-commutativity has sometimes been seen as a liability, but Morgan would like to flip that on its head. He thinks classical mechanics should be modified to make it more like quantum theory, rather than the other way around. The Koopman-von Neumann formulation gets it partway there, but to fully match quantum theory’s flexibility, classical mechanics also needs non-commutativity. Morgan proposes a way to introduce non-commutativity into classical systems, which he claims should provide a way to go between classical and quantum descriptions.

During our second conversation, I again felt unsure whether I would be able to do justice to Morgan’s scheme. To be frank, I found myself agreeing with nearly everything he said on a philosophical level, but I couldn’t see what this had to do with the usual pragmatic applications of classical and quantum theory. The back half of “An Algebraic Approach to Koopman Classical Mechanics” discusses a specific experiment, but the analysis at that point seemed to be exactly what one would expect from quantum theory—with nothing “classical” in the picture.

Happily, Morgan let it slip during that talk that he had himself written a few popular expositions of these ideas when his paper was published, which I realized let me off the hook. (I now dutifully link to these essays—here, here, and here.) Still, as my every-two-months column deadline for 3QD drew near, I began to wonder how these conversations with Peter Morgan could be summarized.

While washing dishes one evening, I listened to a conversation with Jacob A. Barendes, one of the young hotshots of stochastic processes who Morgan had mentioned in his earlier email. Barendes was a guest on Theories of Everything with Curt Jaimungal, defending his ideas against Scott Aaronson, the quantum computer scientist. At the beginning of the show, Barendes defended his idea that quantum theory should be written in the statistical language of random variables. Aaronson, while not totally dismissive, positioned himself as a “potential customer” who was going to pass. Why should he bother with an approach that seems to be “adding additional ontology without adding an additional story”?

That gave me pause. What, exactly, was CM+ giving me that I needed? I reached out to Morgan again, and we agreed to speak again on July 10.

This time, I came with a list of firm questions. I wanted to know how the specific mechanism that Morgan proposed for introducing non-commutativity into classical mechanics made a difference for experimental analysis. I wanted to know how CM+ could work in situations with well-defined initial conditions and dynamical change, since his paper’s expository example was only defined in a static thermal state. I wanted to know how CM+ might gel with those famous historical examples that textbooks routinely list as the final assassins of the classical paradigm (e.g., the hydrogen atom, the Stern-Gerlach experiment, etc).

I wanted to find out if I would become a customer.

Peter Morgan and I had another lovely conversation, but to my mind he was not able to answer any of these questions. He admitted that the harmonic oscillator analysis in the early parts of the paper had little to do with the experimental analysis of the later parts, but hoped that the experiment would look different once framed in the context of classical non-commutativity. On other questions, he was frank about not having a full explanation—but what was he to do? Wait another few decades? He may not have that much time left to work.

The sense that time was running out haunted the end of our discussion, as Morgan passionately walked me through his frustrations at getting others to accept his recent work on renormalization. Was there anything to it? I was unqualified to answer. I had not quite become a disciple of CM+, but I had learned many useful things from Peter Morgan in our brief correspondence, and I wished him well.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.