by Dick Edelstein

According to today’s newspaper, Spain is expected to lose some 30% of its population over the next 75 years, based on current birth rate projections, a loss of over eight million inhabitants—too great to cover through the influx of migration (La Vanguardia, 17 May). And what about other European countries? The study cited above predicts a still greater per capita drop in Italy’s population. So why aren’t people more worried about who will supply the labor power that we will need to secure future social benefits, rather than heeding absurd declarations by right wing populists like Meloni and Trump on the supposed dangers of migration?

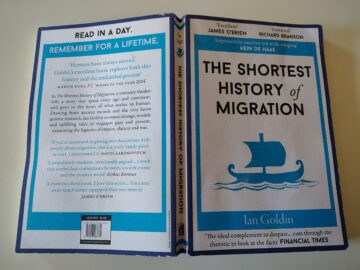

At a time when it is essential to be able to separate the facts and realities of migration from the myths and lies, author Ian Goldin offers us timely assistance in a brief book entitled The Shortest History of Migration, an indispensable guide when the facts of migration are obscured by a baseless hysteria whose effects span the political spectrum, influencing the attitudes of groups and individuals on the left as well as the right. This is an opportune moment to take a good look at those facts. The author, with a gift for synthesizing detailed material, has produced a concise book, with an apt cover blurb that says: “Read in a day. Remember for a lifetime.” Goldin takes a very long view, explaining to readers how migration has always been an intrinsic part of the evolution and development of the human race as he traces the phenomenon throughout all of the eras of human history.

As a migrant myself, and someone whose recent ancestors migrated from Europe to the New World for some of the reasons succinctly described in this book, for me this is a personal as well as a social question, although most people have some personal interest in migration as well as their own viewpoint. So, when separating the facts from the myths of migration seems like a Sisyphean task akin to picking the fly shit out of the pepper, Goldin comes to our aid with a brief, thoughtfully traced and schematic view of a phenomenon that remains a burning issue even though it has been with us since our beginnings. As a European resident, I know that Western Europe is expected to need some 50 million migrants over the next few decades to meet labor needs, and I worry that the African share of that migration might not be large enough to truly help kick-start that continent’s economic development.

In the early chapters of his book, Goldin follows the traces of the first migrants, the Homo sapiens who roamed the African continent from Morocco to South Africa, and he charts their eventual migration to Europe and beyond. He shows how our ability to migrate and adapt to new challenges is an intrinsic part of what makes us human, an important driver of the early development of humanity. And we learn about the effect of the invention of the wheel on human migration. Succeeding chapters examine the population of the planet by humans, later voyages of discovery and conquest in both the eastern and the western hemisphere, the role played throughout history by slavery, the rise of empires, and eventually—in Chapter 7—“the age of mass migration”.

Goldin highlights the fact that the era from the mid-nineteenth century to the start of the First World War was like no other in terms of the number of people who moved or were displaced and the distances they covered. Mass emigration to the New World was driven by a search for a better life, but also by rapid population growth, political upheaval and the flight from the land due to higher taxes, loss of rights to common land and hunger. For example, famine stalked poor rural populations in Europe who were dependent on the potato when the crop was destroyed by blight over a number of decades, particularly in Ireland. By the middle of the nineteenth century steamships were providing a cheaper, safer and faster route for ocean crossing. And, by the end of the century the rise in antisemitic movements and the chilling effect of pogroms in Eastern Europe were generating significant migratory flows to both North and South America.

The rise of nationalism in the newly configured Europe in the decades leading up to the global conflict in 1914 led to stricter control of borders, the advent of passports and eventually the end of people’s freedom of movement. These changes were consolidated by the divisive effect of the war; and by the middle of the century, passports and visas had become the norm, creating a new set of problems for migrants fleeing conflicts, genocide, misery and ethnic cleansing. A brief history of the partition of India illustrates how the lives of millions can be affected by colonial conquest and political upheaval. Goldin also cites the story of the betrayal of the Caribbeans encouraged to come to Britain to live and work in 1948 on the Empire Windrush passenger ship, who, over 60 years later, were denied their rights as British citizens, a disturbing example that puts the question of migration in a contemporary perspective.

The second part of the book deals with the present reality and the future of migration. Here we learn that migrants who left their home countries after the Second World War made up a far higher number than today’s 3 million migrants crossing the ocean. The second great migration of the 20th Century was composed of the 5 million African Americans whose ancestors had arrived in slave ships, when they themselves migrated from the American South to the industrial Northwest and Midwest, often to take up work in factories. Other contemporary topics discussed include digital nomads, the impact of migration on economic and social development in destination and sending countries, the pain of exile, the power of the diaspora, and migration as the great disruptor of our times.

Readers might well wonder what advice Goldin offers to help us deal with the many migration-related social problems that affect most citizens in every country in the world. The answer is that he offers none since those issues are outside the scope of this book, and a very thick book would be needed to even broach that subject. But Goldin has done very well to circumscribe the purpose of his book in order to make it sufficiently concise to attract a broad readership and make a contribution to the Augean task of clearing up the fog surrounding migration in order to elucidate many of the pertinent facts.

This is a book that you can actually read in a day. It relates details familiar to some readers that will be new and surprising to others, and it is organized in a way that avoids boring readers with pedantry when the author reviews territory that may be somewhat familiar. Above all, the book is concise, easy to read and eminently timely.