by Jochen Szangolies

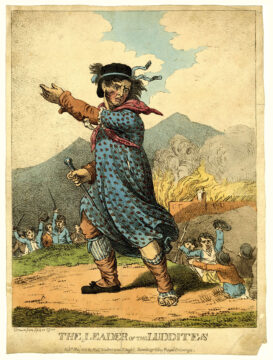

When the Luddites smashed automatic looms in protest, what they saw threatened was their livelihoods: work that had required the attention of a seasoned artisan could now be performed by much lower-skilled workers, making them more easily replaceable and thus without leverage to push back against deteriorating working conditions. Today, many employees find themselves worrying about the prospect of being replaced by AI ‘agents’ capable of both producing and ingesting large volumes of textual data in negligible time.

But the threat of AI is not ‘merely’ that of cheap labor. As depicted in cautionary tales such as The Terminator or Matrix, many perceive the true risk of AI to be that of rising up against its creators to dominate or enslave them. While there might be a bit of transference going on here, certainly there is ample reason for caution in contemplating the creation of an intelligence equal to or greater than our own—especially if it at the same time might lack many of our weaknesses, such as requiring a physical body or being tied to a single location.

Besides these two, there is another, less often remarked upon, threat to what singer-songwriter Nick Cave has called ‘the soul of the world’: art as a means to take human strife and from it craft meaning, focusing instead on the finished end product as commodity. Art is born in the artist’s struggle with the world, and this struggle gives it meaning; the ‘promise’ of generative AI is to leapfrog all of the troublesome uncertainty and strife, leaving us only with the husk of the finished product.

I believe these two issues are deeply connected: to put it bluntly, we will not solve the problem of AI alignment without giving it a soul. The ‘soul’ I am referring to here is not an ethereal substance or animating power, but simply the ability to take creative action in the world, to originate something genuinely creatively novel—true agency, which is something all current AI lacks. Meaningful choice is a precondition to both originating novel works of art and to becoming an authentic moral subject. AI alignment can’t be solved by a fixed code of moral axioms, simply because action is not determined by rational deduction, but is compelled by the affect of actually experiencing a given situation. Let’s try to unpack this.

Once Moore With Feeling

A famous thought experiment due to philosopher and ethicist Peter Singer goes as follows. On your way to work, you encounter a small child, unattended, in danger of drowning in a shallow pond. To you, there is little danger in wading in and saving the child, safe that it would ruin your new Armani shoes. What should you do?

The answer, of course, is clear: the loss of your new shoes is inconsequential in comparison to the loss of a life, so there is no question you should jump in and save them. Singer then has you on the hook: nothing in the moral calculus depends on your physical proximity to the endangered child. And there are endangered children all over the world that you could aid, right now, without any danger, at an expense probably far less than that of a pair of Armani shoes. So why don’t you?

The basic philosophical idea here is that of utilitarianism: that those acts are good that maximize utility—roughly, that bring the greatest good to the most people. In recent times, it has also stood at the origin of effective altruism, the doctrine that we should not only do good, but do so as effectively as possible.

I don’t wish to debate the philosophical merits of either approach here. But at their origin, there is an assumption that is rarely questioned: that we act (or at the very least should act) according to some set of rules governing our actions. In deciding whether to save the life of the drowning child, we’re asked to weigh this life up against the cost and inconvenience to our person we would incur. That cost might be too great: in workplace fire drills, one is routinely advised to leave unconscious people behind due to the likelihood of endangering both your lives in attempting to save them.

So only if the calculus checks out, you should take action. Now, this in itself already invites uncomfortable questions: it might be that the unsoiled Armani shoes fetch a price, if resold, which donated to the right charity could save multiple lives, rather than just one. But more seriously, this simply isn’t the way we act at all—moreover, it can’t possibly be. It is not a coherent thing to strive for, since rational reasoning alone compels no action.

It is entirely possible to reason dispassionately through the calculus of Singer’s example, and then, just not to act. To be moved to action needs a further impetus given by the valence of the situation: we save the child simply because we are compelled to do so. What spurs us into action is an affective state arising in response to the situation, which translates into a physical response of alertness, quickened heart rate, heightened senses and racing thoughts—it is this change in our being in the world, not considerations of the relative values of Armani shoes, that makes us jump into the pond.

No system of rules and regulations can replace this immediate and visceral reaction, because they can’t make us want to do—or not to do—anything. From mere facts and operations on them, no moral imperative follows—what philosophers call the ‘fact-value distinction’, most memorably pointed out by the Scottish philosopher David Hume.

Now, neither utilitarianism nor EA need fall afoul of this issue. We can assume a shared background of human values, with each framework merely supplying rules as to how best to live accordingly. But crucially, this presupposition is absent in AI, and thus, all attempts at AI alignment collapse to trying to formulate a system of rules to replace the valence of experiencing a certain situation that grounds all action—moral or otherwise—in us. It is ultimately this affect that makes us act, that compels us to act in a certain way, and AI is entirely devoid of it.

Note that I’m not saying that you act in a morally permissible way only if doing so makes you ‘feel good’, thus giving every action an ultimately self-serving justification. It is not your desire to feel any particular way that makes you act such as to bring about that feeling, it is that feeling a particular way in a given situation makes you act, in the same way that feeling the need to for oxygen makes you breathe. You don’t breathe because you expect a reward in carrying out that action, you breathe because the urge to do so is inherent to the feeling of lacking oxygen, until at some point you can’t help but follow it. Likewise, the urge to act and save the drowning child’s life is inherent to the situation’s affect, to how you feel when seeing a fellow human in danger.

Emotional valence, not rational calculation, is the motivator of human action. This is precisely as it should be—as Hume, once more, put it, ‘reason is and ought only to be the slave of the passions’. A real-world Mr. Spock simply would never find any reason to act any particular way in his logical deductions.

Consequently, in trying to create a (to whatever capacity) reasoning agent that then follows some calculus of moral action such as not to rise against its masters, we are then already mistaken at the outset. In his 1903 book Principia Ethica, the English philosopher G. E. Moore has called this the ‘naturalistic fallacy’: attempting to derive evaluative conclusions (i.e. conclusions about what one ought to do, or what value to attach to an action) from non-evaluative premises.

Act And Art

It is here that we can circle back to ‘the soul of the world’, to the creation of art, the evaluation of lived experience. When a situation, through its affect, urges us into action, we are—for the most part—not strictly compelled to follow this urge. In general, any situation will confront us with multiple, conflicting urges, such as my urges right now to finish writing this piece, or have lunch first. We may think of these urges as paternoster cabins moving upwards: only if we decide to step onto them do they sweep us along. Of course, some urges, such as the one to breathe, may become overwhelming eventually; but in general, we find ourselves capable of choice.

Now, choice is where novelty enters the world. It is the origin of creativity: where the world bifurcates into mutually exclusive options, choosing one instead of the other brings a new element into being (otherwise, there would not have been a choice). Or, to put it the other way around, as science fiction author Ted Chiang does, any wholly deterministic system can’t originate anything novel, because all it will ever do is already entailed by its inputs. (The randomness that modern AIs exhibit is just a deterministic simulation, known as ‘pseudorandomness’; reset it to exactly its prior state, including any ‘seeds’ used for pseudorandomness generation, and its outputs will match perfectly.) This echoes the great analytic philosopher Bertrand Russell, who might just as well have been talking about ChatGPT and its ilk when he wrote that “the method of ‘postulating’ what we want has many advantages; they are the same as the advantages of theft over honest toil”.

There is an obvious difficulty in appealing to choice her: choosing, it would seem, is itself an action. If all actions are the result of urges, which we can (to some degree) choose to follow, we are on our way to vicious regress. My reply to this is that choice is a primitive notion that can’t be further analyzed. This seems to be a cop-out, but if so, it’s a common and widely shared one: any account of how novel information enters the world is just such a black box. Random events just occur, without any reason why. The universe, traced back to its origin, just pops into existence—if it doesn’t exist eternally. Wherever we trace things to their supposed ‘absolute’ origin, we find a black box that can’t be further analyzed.

I believe this is just an artifact of the way explanation works: deriving consequences from premises can’t generate information not already present within those premises. Thus, we face the Münchhausen trilemma: trying to go beyond those premises, we are met with either circularity, regress, or bland stipulation. But there is no reason for the world to be as limited as our faculty of explanation is; hence, recognizing that we will always have to admit a black box somewhere, putting it where choice is supposed to go is at least not making anything worse.

Continuing on the basis of this stipulation, the affective valence of a situation, the way its subjective evaluation urges us into action, gives us options, while the choice between these options, which urge to give in to, which action to take, introduces genuine novelty into the world. This is the aspect of our being both at the root of moral action and the creation of art (or creation at all, period)—and it is entirely absent in current AI. AI output can never be art in the same way that it can never be a moral act. To produce art, as well as act in a morally meaningful way more generally, needs both the pathos of our lived experience, as Nick Cave urges, and the ability to make true choices not reducible to prior inputs, as Ted Chiang notes. This makes the creative act literally part of the continuing unfolding of creation: a new aspect of the world is brought into being every time a choice is made.

If we thus want to create human-like artificial beings (a big if, to be sure), and want them to be morally accountable entities, we need to endow them with capabilities that will also make them genuine producers of art. We need, in other words, to make them feel. It is then telling that there seems to be precious little research into imbuing AI with emotional states; most articles connecting emotion with AI seem to be concerned with getting artificial agents to respond appropriately to our emotions. That we are nevertheless being promised human-like artificial minds on a timescale of months to years speaks to a strangely parochial image of the human mind as a ‘calculation engine’ that still pervades the fundamental assumptions of machine intelligence. In truth, nobody today knows how to bridge this gap, how to give an artificial agent the lived experience and meaningful choice characteristic of human mental life.

I have considered both of theses issues at some length in these pages previously. For now, let me just offer up a hint that they are not truly separate. Consider a toy robot, programmed to navigate a labyrinth of a certain size: if we give it a fixed system of rules for how to turn at what juncture, it will just carry out those movements regardless—‘mindlessly’, if you will—even if the walls aren’t actually there. For such a fixed-rule machine, the outside world effectively plays no role, need never be present—it is decoupled from any outside influence. Its performance may well be perfect, just as the performance of an AI at some carefully circumscribed task may be, but in a very real sense, it just doesn’t know what it’s doing.

The trouble with this is that the world isn’t a labyrinth of fixed size. Consequently, there is no fixed-size set of steps we can program into the robot to navigate it. Rather, an agent needs to be, in some sense, able to experience itself within the labyrinth—the outside world needs to be present to it—in order to generate options, and be capable of genuine choice to bring anything novel into being, to act rather than merely react. It is only where we are confronted with options in the world—where we bump into it and find our reservoir of pre-fixed judgments and assumptions exhausted—that experience and thought arises, and the automaton has neither.

Of course, the troubling conclusion then is that any attempt to make AI ‘align’ with our interests would be tantamount to slavery. It might solve the ‘problem’ of alignment: it is, in the end, not all that hard to manipulate affect towards a desired result. The problem is often described as the impossibility of controlling an entity smarter than yourself: but the single-celled Toxoplasma gondii readily achieves its aim of getting its host, the much smarter rat, eaten by a cat, to take up residence and mature in the latter—it just takes away the rat’s reason to act, its fear response. Controlling the affect enables control of the entity, without any need to create rules that outsmart its aims. By manipulating affects, control can be exerted over those that are both smarter and more powerful, as centuries of human bondage in various guises, of rule of the few over the many, attest to. But is that really the way we want to move forward?