by Ashutosh Jogalekar

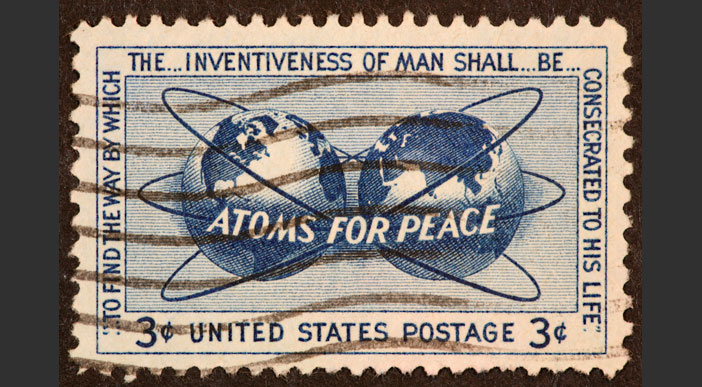

The visionary physicist and statesman Niels Bohr once succinctly distilled the essence of science as “the gradual removal of prejudices”. Among these prejudices, few are more prominent than the belief that nation-states can strengthen their security by keeping critical, futuristic technology secret. This belief was dispelled quickly in the Cold War, as nine nuclear states with competent scientists and engineers and adequate resources acquired nuclear weapons, leading to the nuclear proliferation that Bohr, Robert Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard and other far-seeing scientists had warned political leaders would ensue if the United States and other countries insisted on security through secrecy. Secrecy, instead of keeping destructive nuclear technology confined, had instead led to mutual distrust and an arms race that, octopus-like, had enveloped the globe in a suicide belt of bombs which at its peak numbered almost sixty thousand.

But if not secrecy, then how would countries achieve the security they craved? The answer, as it counterintuitively turned out, was by making the world a more open place, by allowing inspections and crafting treaties that reduced the threat of nuclear war. Through hard-won wisdom and sustained action, politicians, military personnel and ordinary citizens and activists realized that the way to safety and security was through mutual conversation and cooperation. That international cooperation, most notably between the United States and the Soviet Union, achieved the extraordinary reduction of the global nuclear stockpile from tens of thousands to about twelve thousand, with the United States and Russia still accounting for more than ninety percent.

A similar potential future of promise on one hand and destruction on the other awaits us through the recent development of another groundbreaking technology: artificial intelligence. Since 2022, AI has shown striking progress, especially through the development of large language models (LLMs) which have demonstrated the ability to distill large volumes of knowledge and reasoning and interact in natural language. Accompanied by their reliance on mountains of computing power, these and other AI models are posing serious questions about the possibility of disrupting entire industries, from scientific research to the creative arts. More troubling is the breathless interest from governments across the world in harnessing AI for military applications, from smarter drone targeting to improved surveillance to better military hardware supply chain optimization.

Commentators fear that massive interest in AI from the Chinese and American governments in particular, shored up by unprecedented defense budgets and geopolitical gamesmanship, could lead to a new AI arms race akin to the nuclear arms race. Like the nuclear arms race, the AI arms race would involve the steady escalation of each country’s AI capabilities for offense and defense until the world reaches an unstable quasi-equilibrium that would enable each country to erode or take out critical parts of their adversary’s infrastructure and risk their own.

With software now intimately embedded in the electrical grid, agriculture, transportation and other core parts of a country’s basic infrastructure, and with all these parts interdependent and interconnected through the Internet, AI could have a catastrophic effect on a country’s essential services, including hospitals and first responders, food and water supplies and the basic levers of government. Countries could potentially be brought to their knees overnight and turned into targets for coups and takeovers.

Needless to say, governments around the world worry about such existential scenarios, but there has been a relative lack of transparency and joint efforts in mitigating such catastrophes. How do we ensure that AI is developed responsibly and that we reap its maximum benefits while avoiding the kind of dangerous arms race that was set up between the nuclear powers? The Cold War taught us that the answer lies in common security enabled by cooperation and open exchange; you can only feel secure when your adversary feels secure. The treaties and frameworks for reducing the threat of nuclear weapons provide a blueprint for reducing the threat of AI.

What would an “AI treaty” look like? At the outset, it should be importantly realized that unlike arms control treaties which emphasize control over things like the number of warheads, delivery systems etc., because of the ubiquitous existence of AI models in both the public and the private sector, an AI treaty would focus on access rather than control. This mirrors the access for inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) enshrined in several arms control treaties. An AI treaty would focus mainly on two things: sharing data and models, and restricting applications. Since every country possesses legitimate economic and national security secrets that add value to its economy and keep its citizens safe, the exact details of how much to share and what applications to restrict could be worked out by representative national and international committees. Here is a potential framework that lays out the terms and conditions that might be involved in an AI treaty between two countries, say the United States and China.

1. Requiring Transparency and Disclosure

- Inspection and Verification: An international body could conduct regular audits on AI labs and development facilities, ensuring adherence to safety protocols and testing criteria. Inspections would help verify compliance with treaty standards while preserving intellectual property and confidentiality.

- Algorithm and Dataset Disclosure: The “black box” nature of many AI models creates risks of hidden biases, unethical behavior, or unintended outcomes. To address this, countries could agree to share certain details about their AI algorithms and datasets—perhaps not the full code but key aspects that reveal how they operate and mitigate risks. This might include outlining data sources, model training processes, and intended usage to build international trust. There are specific techniques like zero-knowledge proofs, used for warhead verification for instance, which could potentially be applied to assessing equivalence of AI models, or adherence to a particular benchmark, without sharing the underlying data.

2. Limiting Military Applications

- Ban on Autonomous Lethal Weapons: The use of AI in autonomous weapons poses severe ethical and existential risks. The kind of drone warfare that we have seen in the Russo-Ukraine war could easily turn exponentially lethal once AI starts controlling drone behavior in a self-catalyzing, autonomous manner. The treaty could therefore mandate a ban on fully autonomous lethal weapons—those able to make decisions on using force without human oversight. Such provisions could cover drones, robot soldiers, and autonomous naval or aerial attack systems, requiring a human “in the loop” for any decision to use lethal force.

Beyond autonomous weapons, the treaty could restrict AI’s role in offensive operations, including cyberattacks, disinformation, and electronic warfare. Nations might be required to declare and register any AI system used in defense to ensure compliance, with some applications restricted to non-combat, humanitarian, or defensive-only roles.

3. Implementing Ethical and Fair Use Guidelines

- Prohibition of AI for Mass Surveillance or Repression: AI-powered surveillance, like facial recognition and biometric tracking, has been used in ways that infringe on human rights. A treaty could limit these applications, especially for mass surveillance or social scoring, as seen in some nations, and could encourage transparency on data collection. Only law-enforcement applications that meet strict standards on privacy and legality might be permitted.

- Bias Auditing and Correction: Many AI systems reflect biases present in the data they’re trained on, leading to unfair treatment of certain groups. Treaty terms could require countries to audit their AI systems regularly, particularly those used in sensitive areas like law enforcement, hiring, banking and education. Bias correction protocols would guide developers on identifying biases in data and applying corrective algorithms.

4. Adopting R&D Safety Standards

- Risk Assessment Protocols: High-risk AI developments, especially in areas like artificial general intelligence (AGI) or advanced autonomous systems, carry unique risks. A treaty could mandate that any research surpassing certain levels of AI capability undergo preemptive risk assessments submitted to the regulatory body. Thresholds beyond which AI models’ capability becomes concerning could be defined by mutually agreed upon training benchmarks, or a step change in computing power utilization or electricity consumption by AI data centers. These assessments would ensure that developers consider worst-case scenarios and implement necessary safeguards.

- Fail-Safe Mechanisms: The inclusion of fail-safe mechanisms in advanced AI systems would add a layer of control to prevent unintended escalation or harmful decisions. These might include manual shutdown processes, emergency stop buttons, or controlled shutdown protocols triggered by specific conditions. Developing these standards internationally could help prevent catastrophic failures or unintended harm. AI models which cannot progress beyond a certain threshold without a human in the loop would lend themselves to safer development.

5. Implementing Data Privacy and Security Protocols

- Personal Data Protection Standards: AI is heavily reliant on personal data, making privacy and security essential. This provision would establish international standards on how personal data is collected, stored, and used by AI systems, requiring adherence to strict privacy principles. Nations could agree on certain rights to personal data ownership, such as the right to be forgotten, data minimization, and robust data encryption methods. This framework would be especially critical in the use of AI models in healthcare or law enforcement.

- Cross-Border Data Sharing Agreements: Countries might want to share data for collaborative AI projects while respecting privacy laws. A treaty could establish a framework for safe data sharing, focusing on anonymization, encryption, and clear boundaries on data usage to prevent misuse. Such agreements would promote collaborative development while safeguarding privacy and security.

6. Establishing an AI Incident Response Network

- Rapid Response to AI Failures or Accidents: One of the ways in which countries deal with the risk of nuclear proliferation is to implement rapid response teams like NEST which can be deployed speedily at the site of action of a nuclear accident, whether intentional or unintentional. AI systems occasionally fail or behave unpredictably, which can lead to accidents, financial losses, or other forms of damage. A global AI incident response network would allow nations to coordinate rapidly in such cases. This network could share information on incidents, provide shared resources for containment and investigation, and offer support to affected parties.

- Crisis Communication Channels: In cases of suspected AI misuse or potential threats (like an AI-driven cyberattack), predefined, hardened communication channels would allow immediate information sharing between countries. This could help mitigate damage, prevent the escalation of tensions, and allow quick remedial action, reducing potential fallout from malicious or accidental AI misuse.

7. Ensuring Global Equity and Access Provisions

- Resource and Knowledge Sharing for Developing Nations: Many developing nations lack the resources to keep up with rapid AI advancements, putting them at a potential disadvantage. An AI treaty could facilitate knowledge sharing, including open-source code, data sets, training modules, and resources to help these nations develop their AI capabilities safely and responsibly, thereby preventing global inequities from deepening.

- Preventing Economic Exploitation by Advanced AI Systems: Powerful nations could use AI to manipulate markets, extract resources, or gain economic control over weaker states. Treaty terms could prohibit exploitative AI practices, ensuring that AI is used ethically in global trade and economic transactions. Provisions may also encourage shared economic benefits from AI developments, fostering a collaborative approach to growth.

8. Implementing Accountability and Enforcement Mechanisms

- Sanctions for Non-Compliance: To ensure adherence, the treaty would include a mechanism for imposing sanctions on countries that violate its terms, whether through economic penalties, technology restrictions, or other punitive measures. These sanctions would incentivize compliance and create real consequences for unauthorized or reckless AI development.

- International AI Court or Tribunal: Given the unique nature of AI-related disputes, an international tribunal would provide a neutral forum for resolving conflicts arising from AI use, misuse, or treaty violations. This court could mediate cases involving malicious AI development, ethical violations, or harm caused by cross-border AI applications, creating accountability while promoting adherence to treaty terms.

Ultimately, every treaty is only as good as the will of the countries that want to adopt it. But what countries need to realize, as they did during the Cold War, is that by adopting internationally recognized safeguards and standards for AI, they will be able to spend their human and economic capital on the benefits of AI while being assured of an international community and framework that can absorb the shocks and unexpected risks of AI development. They will be able to spend almost all their time working on the good instead of worrying about the bad. In the safety of one lies the safety of everyone. In common security lies opportunity.