by Marie Snyder

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

I started reading about burnout when I walked away from teaching earlier than expected. Suddenly, I couldn’t bring myself to open that door after over thirty years of bounding to work. A series of events wiped away any sense of agency, fairness, or shared values. Their wellness lunch-and-learns didn’t help me, and I soon discovered I’m not alone.

An article published in JAMA last June looked at rising rates of burnout in healthcare, where 40% of physicians surveyed intended to leave their practice. They suggest, “To prevent a health care worker exodus, experts argue that the emphasis needs to shift from individual resilience to broader system-level improvements.” They are looking for standardized methods to affect organizational management with “evidence-based interventions.”

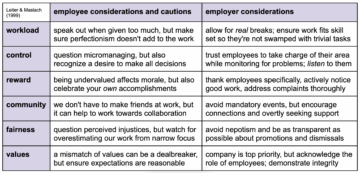

Over 25 years ago, Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach came to the same conclusion. They identified six areas of worklife affecting burnout and created a specific assessment for educators. They determined the cause to be a “mismatch” between employee expectations and employer behaviours leading workers to be closer to the bleak end of a continuum from burned out to engaged. They suggest that “the task for organizations and individuals is to achieve a resolution.” This is not just a matter of throwing wellness initiatives or resilience-speak into the mix, but addressing any reasonable expectations of employees with appropriate employer interventions in all six interrelating areas.

Feels vindicating, right?!

One problem with this solution and possibly a reason why it’s not widespread, however, is that it’s often the employees that hold the highest standards and care for the workplace who are the most affected by burnout, and they might make up a small minority of workers. People who show up to learn the right buzzwords and put in the least effort required to hit their hours without concern for the process and product of the company can feel unscathed, and those employees can make up enough of the workforce to provoke organizations to continue the micromanaging and questionable reward schemes for the many.

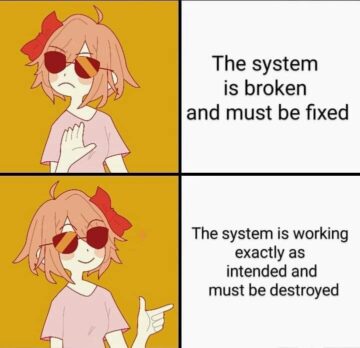

However, perhaps this uncomplaining majority just seems unaffected. It’s not just that we live in a time in which a woman can sit dead at her desk for days without notice, but that there’s an overarching sense of impotence in our lives. The shift of responsibility from workplaces to workers is still seen in the call for self-care measures provided to placate complainers and increase efficiency at work, which lets the company off the hook. But more essentially, the focus on individuals and corporations lets the larger system off the hook.

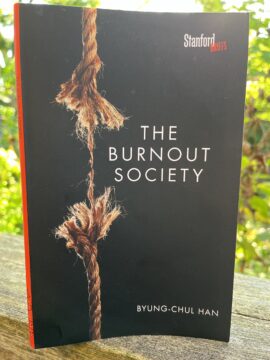

Ten years ago, the Korean-born German philosopher, Byung-Chui Han, discussed the larger system in The Burnout Society. It’s a very short book but dense and complex, and I’ll hardly do it justice here. Han’s next book, Spirit of Hope, is coming out in November, so this is a good time to review his previous work.

Han’s thesis is formed around his delineation of two ages: the bacterial age, which ended with the creation of antibiotics to fight infections, and the neuron age, which brought on a new landscape of pathologies that elude all attempts at combat. (Note that this was written pre-Covid, and now vaccines are less trusted or sought out, and anti-immigration sentiment has been re-ignited; regardless, the metaphor extending to our self-concept is the pivotal proposition.) In the former age, our enemies were external to us, and we made efforts to keep foreign invaders out at the smallest to largest scales: with pharmaceuticals or missiles. We eliminated the other in order to feel safe and secure. However, this “immunological paradigm” didn’t enable unfettered globalization and consumption.

In our current age, we’ve knocked down walls to embrace otherness and increase consumerism to the point of deactivating foreignness as a trigger for attack. “Otherness is disappearing, we are living in a time that is poor in negativity” (5). There are no more bad guys to fight off, but the absence of enemies hasn’t led to a sense of security. Instead of feeling attacked from externals, we are attacked from within in a “violence of positivity”. The harm we experience now is from our own neural activity – from sameness instead of difference. Inoculating ourselves with more of the same doesn’t provoke any defence. Globally, this is seen in excessive production, communication, and consumption. Individually, this looks like excessive positivity in a quest for unlimited achievement and an inability to experience contentment. We’ve been indoctrinated to believe we can have it all and be all that.

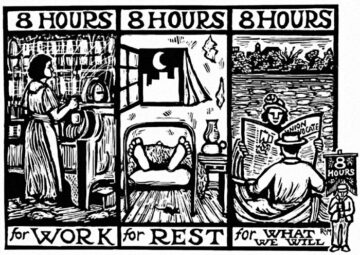

It’s a brilliant system to keep people striving to work faster and for longer hours and to struggle to produce continuously without needing to lock them up. Convince people their potential is limitless, and they’ll unceasingly strive to fulfill it, working as fast as humanly possible to beat a standard, or clocking 100 hours each week in salaried positions, all the while smirking at the efforts of old labour activists to ensure a more reasonable working life as if they’re now somehow beating the system.

Han explains that we used to live in a disciplinarian society as described by Foucault in which we were oppressed by punishment. Now our achievement society oppresses us with self-loathing. Violence from positivity (you should shoot for the stars, you can be anything you can dream up…) doesn’t require hostility, so we haven’t developed any type of defenses against it. Instead of an infection, Han calls it an infarction (6), an internal blockage that saturates and exhausts us. Instead of an external SHOULD that we are inspired to question, reject, and fight against both individually and in groups, we have an unlimited CAN that we desperately want to believe, which doesn’t feel like a problem. It’s Aristotle’s vice of excess from a rejection of containment of any kind, and we’ve been warned about it over thousands of years from Ezekiel, Plato, Seneca, Jesus and so many political philosophers. We need limits.

We buy into this rejection of boundaries in part because recognizing our limitations means acknowledging our finitude. We will age. We will slow down. And we were never that great at basketball in the first place. Striving helps us avoid accepting our own death, but it also ensures we avoid our own life.

We still have prisons and factories, of course, and factories in prisons, but that’s just for a few. The rest of us are affected by “another regime, namely a society of fitness studios, office towers, banks, airports, shopping malls, and genetic laboratories. . . . The drive to maximize production inhabits the social unconscious” (9). Instilling a fear of punishment hit a limit, and it’s much more cost-effective to convince workers they’ll be rich or famous one day than to threaten them. We’re like a donkey chasing a carrot that’s always just out of reach.

Burnout isn’t just from the exhaustion of constantly trying to measure up, but from “an impoverished attachment, which is characteristic of the increasing fragmentation and atomization of life in society” (10). In competition, we are kept apart from one another, all of us believing we’re somehow above the masses instead of being part of humanity. We have individual conditions instead of a human condition. We’ve been set up to rise above each other in a continuous struggle that benefits corporations. We’re not becoming sovereign, über-men with dramatic freedom over ourselves, but Nietzsche’s “‘last man,’ who does nothing but work” (10). We’re willingly exploiting ourselves in a system that doesn’t value us but merely gives us the illusion of freedom.

Burnout “leads to destructive self-reproach and auto aggression” from a fight with ourselves over overinflated expectations of what we should be able to do, which creates an internal war with ourselves. We’ve taken ownership of the problem as if it’s from a lack of willpower while surrounded by distractions, but we can’t bring ourselves to do the work because we’re unable to give up this quest to reach our full potential.

We react to being trapped by Others with a fight, but now we’re trapped by ourselves and don’t know how to rage against that machine except by shutting down. We can’t effectively disconnect and recharge. We’re living like animals forever collecting food and defending our territory, annoyed by moments of solitude. Han says,

***”Deep boredom is the peak of mental relaxation. A purely hectic rush produces nothing new. It reproduces and accelerates what is already available. . . . In the contemplative state, one steps outside oneself, so to speak, and immerses oneself in the surroundings” (13-14).

We can’t really listen or feel heard when we’re all achieving-machines that have lost the ability to “marvel at the way things are” without any product that can prove our time is valuable. Our thoughts, actions, and very being are only as valuable as the commodities produced. We’re driven to find certainty as a means toward efficiency, refusing to choose a movie to watch or a book to read without first scrutinizing the reviews to make sure it’s worth our time, despite having scrolled mindlessly through social media for hours in that quest.

I’d argue that the shift from philosophy to psychology, in a move from exploring the self to creating an illusion of some certainty of the self, may also have played a part in this. Nothing is durable or substantive in our current culture in which the wisdom of elders is seen as ignorant of novelty. When the mysteries of old are lost, we renounce sacred boundaries and become insensitive to joy and indifferent to suffering until every achievement provokes mere relief instead of triumph. Loren Eiseley’s “The Star Thrower” touched on this loss 50 years ago.

Han relates this self-exploitation to the rise of mental health diagnoses, equating burnout with the Muselmänn in concentration camps who became too apathetic to follow orders:

“The reaction to a life that has become bare and radically fleeting occurs as hyperactivity, hysterical work, and production. . . . . The master himself has become a laboring slave. In this society of compulsion, everyone carries a work camp inside. One exploits oneself. It means that exploitation is possible even without domination. . . . The loss of the ability to contemplate . . . is also responsible for the hysteria and nervousness of modern society” (19-20).

His solution is to learn to cast a long, slow gaze, quoting Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols, p. 57,

“One must not respond immediately to a stimulus; one must acquire a command of the obstructing and isolating instincts. . . . All lack of intellectuality, all vulgarity, arises out of the inability to resist a stimulus:—one must respond or react, every impulse is indulged.”

Blindly following every whim feels like freedom, but it’s really a different form of self-imprisonment in which we’re unable to act from our choices. We’re being driven by Plato’s appetite or Freud’s id or living like de Beauvoir’s “serious people” who turn themselves into children to evade responsibility, not realizing that they’ve renounced their own agency in the process. Han suggests we need to reestablish a capacity for contemplation by overcoming all the achievement training.

However I wonder if this capacity of contemplation is open to everyone or if this solution is yet another form of striving. There have always been cave-dwellers who scramble from one pleasure to the next. Aristotle described this most popular group as the “vulgar” and noticed some more concerned with the rules and justice, and just a very, very few willing or able to live contemplatively. This doesn’t seem like a new problem, but possibly an age-old problem that gets re-discovered repeatedly, maybe necessarily. Although one thing that is markedly different from the past is the glorification of meritocracy. As Michael Sandel suggests, we’ve put our faith in a sorting machine that provides the illusion that we each deserve to rise to the status of Kings. Any former perception of limitation has been blown wide open, and our only barrier is our will. Our belief in a fair system of evaluation breeds a very useful complacency and eggs on any shameful instinct to sit still and think a bit.

Han returns to the problem that we have a desire to fight off an enemy but are impotent to act. Our rage has turned to annoyance and anxiety. Positivity weakens the negative emotions like dread and mourning, which can lead to action, but, without a spark under them, turn into depression. Potency comes in the ability to refrain from acting by saying “No”. But burnout creates a different type of inaction: “The preponderance of positivity, only permits anticipation and thinking ahead. . . . Hyperactivity represents an extremely passive form of doing, which bars the possibility of free action” (24). He illustrates this with Melville’s Bartleby in which the character listlessly refuses to act from a void of will that culminates in his death from starvation. We try to overcome this with caffeine or mindfulness exercises to achieve more and more with less intentional effort, but that quest for efficiency and focus plays into the system. From the ancient philosophers, the answer is to restrain our desires or we’ll forever spin in circles putting out as much effort as we can in order to be fully miserable.

This system is genius for getting people to care more about work than themselves.

Instead of being fired up by negativity, positivity has unleashed a lethargy, which “in achievement society is solitary tiredness; it has a separating and isolating effect. . . . Tiredness of this kind proves violent because it destroys all that is common or shared, all proximity, and even language itself: ‘Doomed to remain speechless, that sort of tiredness drove us to violence.'” (31). It’s exacerbated by the feeling of being worthless for being behind in the race. You don’t belong here if you can’t keep up. Han describes we-tiredness as bringing us together in moments of playfulness or calm. By contrast, I-tiredness “annihilates all reference to the Other in favor of narcissistic self-reference” (36).

Han explains the old understanding of the good person: “The Kantian subject pursues the work of duty and represses its ‘inclinations.’ . . . The moral subject represses all pleasurable inclinations in favor of virtue” (37). Can is the new should. Instead of duties or values, our maxims are our wants: “freedom, pleasure, and inclination” (38). We think we’ve freed ourselves from a set of obligations, but that’s an illusion:

“Freedom from the Other switches into narcissistic self-relation, which occasions many of the psychic disturbances affecting today’s achievement-subject.” Without a duty to fulfill, “it is impossible to reward oneself or to acknowledge oneself. . .. The achievement-subject feels compelled to perform more and more. . . . Self-absorption does not produce gratification, it produces injury to the self; erasing the line between self and other means that nothing new, nothing ‘other,’ ever enters the self; it is devoured and transformed until one thinks one can see oneself in the other–and then it becomes meaningless. . . . The feeling of having achieved a goal never occurs” (38-39).

We are agents of consumption and production.. Without a consideration of our character, what we accept and reject after contemplation, and an effort to align our behaviour with our values in order to demonstrate integrity, we lose any sense of self. Furthermore, often being good is at odds with being best at one end and being unfettered at the other. We have developed peak individuality over community with an unspoken mantra that nobody should ever stop us from doing whatever we want, but without any profound exploration of what that want looks like beyond perpetual striving.

We don’t struggle from an inability to say no from a sense of character, but from a desire to be able to do everything, and then are paralyzed by the unending options. This lack of character allows us to be flexible enough to fit any role and any requirement of the system. We’re interchangeable and continuously competing, which heightens both consumption and production.

“Entirely incapable of stepping outward, of standing outside itself, of relying on the Other, on the world, it locks its jaw on itself; paradoxically, this leads the self to hollow and empty out. . . . The function of ‘friends’ is primarily to heighten narcissism by granting attention, as consumers, to the ego exhibited as a commodity.” (42-43).

Depression is from excess positivity as it lacks the “conclusive power of decision” (44). The self “liberates itself into a project” (46). We want to be the best product on the shelf but know that’s impossible, which saps our will, and then our attempts at recovery by collecting copious things and events are never quite enough to feel rested. We are simultaneously our own perpetrator and victim, master and slave.

Han’s book is more revelatory than I can convey, and it left me with an abject disappointment that we have amassed so much knowledge over millennia, yet we’re still subject to a nature that is so remarkably short-sighted that we will destroy ourselves in hopes of winning some imaginary competition. Our challenge seems to be to somehow detach from the outcome of our efforts without losing our job! It’s not enough to convince our company to treat us like human beings; we have to become human by rediscovering our capacity for wonder and a sense of character and integrity instead of tracking reps, calories, scores, ratings, likes, salaries, trips, trinkets, or whatever metric that’s trying to put a number on our value as a mere commodity. We’re more than that. We’re enough.