by Mark Harvey

A week before he died, I drove my good friend and ranch foreman, Rey Rodriguez, to Denver to catch a bus to Chihuahua, Mexico. He was taking a two-week vacation to visit his family there. On the three-hour drive to Denver, we practiced answering questions for the test given to immigrants applying for US citizenship. He had downloaded 100 potential questions onto his phone and had been studying for more than a year to take the test. I often wondered why he didn’t take the test sooner because he had the questions down. Most of the test is composed of the sort of useless memorization you’d find in an American high school in 1950.

Who was Benjamin Franklin? What do the fifty stars on the American flag represent? Where is the Statue of Liberty? Who wrote the Declaration of Independence?

I have no idea how this test ensures that an immigrant will make a good citizen other than ensuring that the applicant knows far more about American history than the complacent homeowner in Pasadena, California, going all red-faced about keeping “illegals” out of ‘America—between bites of avocado that the “illegals” planted, picked, and packed.

We probably went through 60 questions and Rey didn’t miss one. My suspicion is that Rey had very mixed feelings about becoming an official gringo. Like many Mexicans, he had done the Mexico-America dance for years. Traveling great distances from Chihuahua to places like Yuma, Colorado, to work on a giant feedlot, the Central Valley of California to harvest vegetables, or western Colorado to work on our ranch.

He liked America okay and admired certain things about gringos. But his heart and soul were in Mexico. America was a way to stay afloat financially. I asked him what the average wage of a ranch worker in Mexico was and I reckon American ranch workers make in the neighborhood of 10 times as much.

Rey was a tremendous rancher. He grew up on a ranch himself, one of fourteen kids. Many of his brothers and sisters were named from characters in the bible and one of his own sons was named Ezekiel. With so many kids, his parents probably had to run through a few chapters and verses to find enough names. Rey told me a few stories about his childhood and his family pretty much raised everything they ever ate except sugar and coffee. They planted and dried corn for tortillas, had milk cows, goats, and pigs, planted wheat for bread, and beans to eat with their chickens’ eggs.

Having done every aspect of ranching and farming since the age of about six, Rey really knew more about it than all of us. He had what I would call a literacy of the land and an understanding of livestock that bordered on animism. Many were the times that Rey found cattle deep in the mountains that the rest of us couldn’t find. He was a superb tracker and had a certain mind-meld with the way cattle think. His confidence about where stray cattle roamed actually annoyed me a few times because his reasoning made no sense to me. I was doubly annoyed when he was invariably right. I would compare it to a cosmopolitan city kid guessing just where his bros were partying one night in New York: they knew the hot bars, Rey knew the best salt licks and richest grass.

Like so many Mexicans making a go of it in America, Rey was thrifty and resourceful. He had an old Suzuki Jeep that didn’t have reverse and if you looked up the price for the car in a blue book, it would probably suggest salvage value. Rey called his car “The Hummer” and drove it with confidence to buy his groceries once a week. I asked him a number of times if he ever worried about getting in a bind without reverse. In his comforting fatherly way, he would say, “Of course not.”

I’ve always loved that about Mexicans: they lead with confidence no matter what problem you throw at them. When I was a child my parents took the entire family—all eight of us—on a month-long trip from Colorado to the tip of Baja California, and back. In those days there was literally not a single paved road south of San Felipe near the American border. We drove down in an old Willys Jeep and an International Harvester. With the rough roads, inevitably one of the vehicles needed major repairs. The Mexican mechanics were so adept at fixing our vehicles with no spare parts that my parents joked about them being able to do anything with a pair of pliers and a roll of wire. I told Rey that story and he said, “That’s nothing. Give us a pair of pliers and some wire and we’ll build you a spaceship.”

When I was in college studying International Studies, I came across a quote that I love. It was coined by the 19th century Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz and it goes: “Poor Mexico, so far from God. So close to the United States.” I told Rey that quote and he couldn’t stop laughing. Every morning for about a month he would come up to me and say, “Poor Mexico, so far from God. So close to the United States.”

About five years before Rey died, another one of my hired hands died suddenly and too young as well. His name was Romeo and he came from southern Mexico in the state of Chiapas. Romeo was a master fence builder and built a dozen miles of fence on the rockiest most difficult part of our ranch. He was the hardiest of souls with broad shoulders and an artistry with posts and wire. If you’ve ever carried an eight-foot pressure-treated fence post on your shoulder, you know how heavy and uncomfortable they are to carry. Romeo would carry two of those on his shoulders. One day he stopped to chat with me—two posts on his shoulders. We talked a good 10 minutes and he never set the posts down. I think I felt more pain in my shoulders vicariously than he did suffering the real thing.

One spring he told me he wasn’t feeling well. He showed up at work pale and sweating and weak. I sent him home thinking it was the flu. He showed up again the next day, still weak and pale. I bought him a juicer with the best of Gwyneth-Paltrow intentions but it didn’t cure what was later determined to be Leukemia. A week later he died, still in his thirties with two young sons.

A huge number of people came out for Romeo’s funeral and we walked a mile from the Church on a Colorado hillside to the cemetery carrying his coffin, with a Mariachi band playing songs by request. His coffin and that rugged fencer inside weighed a ton and it hurt my shoulders as much as those heavy fence posts in the bit I acted as a pallbearer. My request for the Mariachis was “Entierrame Cantando (bury me singing).

The thing about the unexpected death of someone you love is that it hits you in the chest with brutal force. Even those of us wildly out of touch with our feelings can connect the figures. When we wake up sad, moping, scared, and kind of teetering on the edge of the bright universe—looking into the void—we know it’s because a living, breathing, joking, irreverent friend left us and our living worlds forever. It’s sharp and it’s awful. None of the palliative “he died doing what he loved” helps a bit.

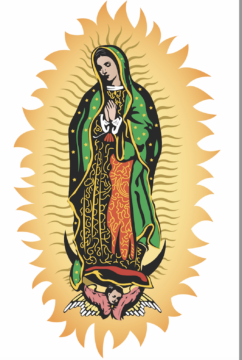

When Romeo died, Rey said that he was in the sky building fence for God. The verb he used was one of those Spanglish words as in “fenciando.” Rey and I often talked about God and he was always surprised that I didn’t believe in his God or his Catholicism. But it was not a proselytizing thing, just a real surprise as if I didn’t know what the fifty stars on the flag stood for or who Thomas Jefferson was. Rey had a sweet spot for the Virgin of Guadalupe, always calling her La Virgin and asked me if I at least believed in her. Again, he was flabbergasted when I confessed ignorance.

I loaned Rey a bit of money one summer and it took him two years to pay me back. When he finally did pay me back, I dropped to my knees and said, “Now I believe in La Virgin.”

Rey was tack sharp. But I would call it a native intelligence born of years of fixing tractors, riding horses, irrigating, branding cattle, welding and the like. I don’t know what level he reached in school but his written Spanish was horrendous. He would glue several words together in the Germanic style and it would take my best Wordle skills to untangle what he meant in his texts. Sometimes I would literally stare at his texts for several minutes, sounding them out phonetically, thinking of the context and then when I’d finally figure it out (“we need more hay” or some such) it would feel like I had solved the Sunday crossword.

When Rey first came to our ranch, he was heartbroken from losing his mother, his father, and his wife, all in the period of about a year. He was obviously struggling with it internally but he was also a stoic and never let those fast losses break him. After some mourning, he remarried had another son, and returned to the joys of his life.

Rey died of a heart attack. His brother told me that he was in the midst of working on his ranch in Mexico, cutting and drying corn. He never stopped working, but I don’t think that’s what caused his heart attack. I genuinely think he loved ranching. As active as he was, I assumed he’d have another 25 years of hard work in him. But with matters of the heart, you never know.

Rey and I were in some ways of opposite disposition. He was far more spontaneous; I sometimes overthink things. He had a supreme confidence in his trajectory and embracing life; I can go a little cynical when things aren’t working out for me. But we were fast friends, loyal to each other, rode hundreds of miles side-by-side on horseback, and talked about everything under the sun.

His spirit, way of being, greeting the mornings and cheering others up reminds me of a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson:

A happy man or woman is a better thing to find than a five-pound note. He or she is a radiating focus of goodwill; and their entrance into a room is as though another candle had been lighted. We need not care whether they could prove the forty-seventh proposition; they do a better thing than that, they practically demonstrate the great Theorem of the Liveableness of Life.

Though I’m not religious, I will concede this: Rey is somewhere in the sky riding a horse searching for those celestial cattle. Goes without saying he’ll find them. Vaya con Dios, Compadre.