by Marie Snyder

Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother’s Hands came highly recommended. The title refers to the effect that being enslaved had on his grandmother, and Menakem traces the violence of racism through the specific perspectives of people on either end of racial conflicts. Beyond just explaining how racism affects all of us in variable ways, he provides specific exercises for overcoming our past. The book contains some excellent and unique ideas about healing from trauma and responding to pain within the context of ongoing racial oppression, but it takes some liberties with explanations of neuroscience and might be better approached as philosophy.

Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother’s Hands came highly recommended. The title refers to the effect that being enslaved had on his grandmother, and Menakem traces the violence of racism through the specific perspectives of people on either end of racial conflicts. Beyond just explaining how racism affects all of us in variable ways, he provides specific exercises for overcoming our past. The book contains some excellent and unique ideas about healing from trauma and responding to pain within the context of ongoing racial oppression, but it takes some liberties with explanations of neuroscience and might be better approached as philosophy.

I’ve previously written about healing advice from Gabor Maté focusing on trauma as the cause of all our ills, Viktor Frankl finding a purpose for himself in order to cope in a concentration camp and advocating for the courage to have an authentic experience of the self and world, Mark Solms reworking Freud to better understand the process of tracing emotional experiences to the past, and the use of Buddhism to stop seeking something outside ourselves in order to find slivers of peace between our thoughts. All of them, more or less, aim to get to something akin to this point:

“Once we can find the spaces between the cacophony of thought, in that tiny gap between trigger and reaction, we can reclaim our agency to decide how to act. When we focus on the nothingness instead of following our personal thoughts and feelings, then we’re no longer dragged along by the drama in our lives.”

Menakem’s book is no different in that respect. This quest has been repeated for thousands of years in various ways and shows up over and over because there’s something to it. It works.

In current psychodynamic terms, we’ve developed maladaptive behaviour patterns that were established to meet some need at a time when we were too young or too overwhelmed to act otherwise. Now we need to become aware of behaviours that don’t work for us, go back to find our error, and reintegrate it all. Menakem goes further than just our personal experiences to look at generational experiences, explaining that,

“traumatic retentions may have served a purpose at one time–provided protection, supported resilience, inspired hope, etc.–but generations later, when adaptations continue to be acted out in situations where they are no longer necessary or helpful, they get defined as dysfunctional behaviour” (39)

I’ve written before about definition creep around “trauma,” and sometimes Menakem stretches the definition: “when something happens to the body that is too much, too fast, or too soon.” Much of what we now use the term to mean was once called baggage. Like the term “abuse,” if we use it too loosely, for instance if we use it to mean any time someone raises their voice in irritation, then two conflicting things might happen: it reduces the power of the word, rendering it less effective when needed, and it makes minor issues feel more harmful, effectively making them more painful and unmanageable. It might make us fearful of approaching a necessary conflict with someone, avoiding speaking up when our boundaries have been crossed for instance, not because it would put us in any potential danger, but because conflict itself has become traumatizing, with a perceived potential to cause longterm damage.

A 2018 study described by Lambert Strether corroborates my concerns:

“They compared rates of PTSD across 24 countries against an index of vulnerability to traumatic events. They expected to find that more vulnerable countries would have higher rates of PTSD, but instead they found the opposite: Countries with higher vulnerability had less PTSD. . . . They hypothesize that PTSD may be a product not just of a life-threatening event itself, but of the degree to which it collides with our expectations. In other words, trauma is the product not only of our subjective experience of an event, but of its interplay with our understanding of the world itself, and of our place in it.”

We can be rattled or overwhelmed by an experience without it being trauma. We need a wider variety of words to express our experiences.

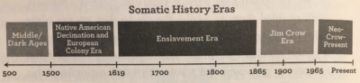

That being said, much of what is discussed in the book aligns all too well with the clinical understanding of trauma: exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, sexual violence, or repeated exposure to aversive details of traumatic events. The repetitive trauma through generations affects production of stress hormones, showing up as “hypervigilance, heightened anxiety, and suspicion.” This helps to explain the Black body experience of being wary of anyone white, the white body “Karen” experience of scrutinizing and reporting anything a Black person does, and law enforcement’s use of preemptive violence.

Menakem approaches the trauma caused by racism by looking at how an ongoing experience of being discounted, overlooked, and/or abused can stay with a person, affecting how they participate in the world. White bodies have a long history of traumatizing each other long before the slave trade, so they see themselves “as fragile and vulnerable.” Many Black bodies “don’t feel settled around white ones” and are seen as “dangerously impervious to pain and needing to be controlled [and/or] potential sources of service and comfort.” The police, or any group in charge of another group, are “charged with controlling and subduing Black bodies by any means necessary.” These are the challenges for us to overcome both individually and collectively.

Menakem explains yet another aspect of the experience by quoting Robin DiAngelo: perceiving “whites as the norm or standard for humans, and people of color as a deviation from that norm . . . an actress becomes a black actress, and so on.” This definition can be extended to any form of discrimination including sexism, transphobia, homophobia, and ableism, which all suggest one kind of person is a deviation of the “right” type of person. He explains, “It’s the equivalent of a toxic chemical we ingest on a daily basis, Eventually, it changes our brains and the chemistry of our bodies.” Menakem focuses on the compounding nature of experiences that piggyback on one another to make our load unbearable. For oppressed groups, that compounding nature is expanded to include intergenerational trauma. The hopeful premise of the book is that if we can each figure out our own issues, then it will help to resolve racial issues in society. Once trauma has ceased and been addressed, growth and positive change become possible once again.

Menakem is a somatic therapist: he recognizes how much our body holds on to these prior experiences. For instance, after a minor accident, we might put up our hands in a defensive position when crossing the street without being aware of this change in our behaviour. Key to healing is getting better at reading our own body, naming feelings, tracing them back to their origins, noticing when we’re triggered in the present, and considering how best to change our response in the future.

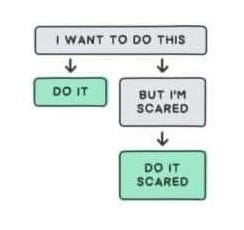

We are going to experience pain in the future, and he divides our potential experiences into dirty or clean pain: “Dirty pain” is reactive, when we’re being led by our “lizard brain” and acting without thinking. “Clean pain” is responsive, when we’re able to lead the way through the issues, conscious and conscientious. To get better at having “clean pain,” we need to practice to develop the recognition of and tolerance for discomfort in the body, the ability to soothe our body, and an understanding of the origin of our triggers so we respond to what’s in the present, not the past.

Menakem’s steps to healing are similar to other psychodynamic practitioners. He calls them the five anchors, which are to be used whenever triggered by an event:

- soothe yourself to quiet the mind and settle the body using grounding exercises

- slow down to notice sensations in body instead of reacting immediately to them

- accept discomfort instead of trying to stop it or avoid it, and notice when it changes by practising regularly

- stay present and in the body and “respond from the best parts of yourself”

- safely discharge any energy that remains through physically vigorous activity (exercise, dance, walking, sports, physical labour …) (168-172)

He clarifies that, “I didn’t wrestle or mold or manage an unsettled nervous system into a settled one. Over time, I learned to access a settledness that is always and already present. . . . Learning to settle your body and practicing wise and compassionate self-care are not about reducing stress; they’re about increasing your body’s ability to manage stress” (152-3). However, he cautions that being settled is not always the ideal response because sometimes we need our fight/flight response activated! Furthermore, we should be careful not to use body-settling skills to disengage or disassociate: a calm Zen persona could mean someone’s doing well on this or that they’re resisting any knowledge of the stuff going on with them. He explains,

“Some people learn to settle their bodies, but misuse that ability. Instead of inviting and accepting healing, they use settling in a neurotic way, to avoid healing. When they face a conflict or difficulty, they don’t settle themselves and then work through the clean pain. Instead, they flee the situation, and then partly soothe and settle their bodies with meditation, prayer, yoga, hiking, and so on. . . . Others, in an effort to avoid anxiety and hypervigilance, over-settle their bodies into a state that resembles depression” (153-154).

Also key to healing is working through tracing feelings back to earlier experiences in order to reduce the magnitude of their effect by finding someone who can listen to descriptions of pivotal events with “full attention, a calm presence, and a settled body” (177). Trauma is “attempted action that got thwarted and became stuck in the body” (178), so we need to complete the action either literally or symbolically through personal storytelling. What I really appreciate about this call to action through self-healing is that he doesn’t just advise therapy, but also gives us the tools to work together down this path.

The exercises throughout the book have us practice experiencing how our body feels when thinking through vivid scenarios so we can be better prepared to understand our physical experiences when faced with a real conflict, calm ourselves, and respond instead of reacting. There are roots in Stoic premeditatio malorum or negative meditations in this practice: We should start each day imagining things that could go wrong and mentally consider ways to act with integrity to meet any difficulty we can fabricate. Seneca advised, “We should project our thoughts ahead of us at every turn and have in mind every possible eventuality instead of only the usual course of events.” Epictetus was more specific about how difficult it can be to be around other people:

“When you set about any action, remind yourself of what nature the action is. If you are going to bathe, represent to yourself the incidents usual in the bath—some persons pouring out, others pushing in, others scolding, others pilfering. And thus you will more safely go about this action if you say to yourself, ‘I will now go to bathe and keep my own will in harmony with nature.’ And so with regard to every other action. For thus, if any impediment arises in bathing, you will be able to say, ‘It was not only to bathe that I desired, but to keep my will in harmony with nature; and I shall not keep it thus if I am out of humor at things that happen.'”

We need to do the work of practicing developing our mental cultivation and attitudes and approaches regularly in order to change how we think, feel, and act with one another in the moment.

This is an important book, and I highly recommend it; however, some of the ideas and terms used don’t fit with current research on neuroscience. I understand that using neuroscience to validate psychotherapy can give it an air of authority and certainty, but used in questionable or contentious ways, it just ends up detracting from the rest of the message.

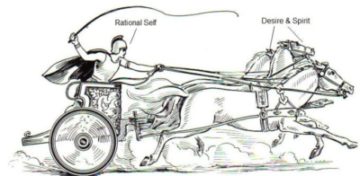

The discussion of the “lizard” part of our brain is from the triune brain theory from the 1950s which has been largely discredited for assuming “a unidirectional flow of information from lower to higher brain systems” and for failing to recognize that,

“Basic neural regions are shared among all vertebrates. Where they differ is in proportion and extent. . . . Second, brain structures do not function independently of one another. . . . Additionally, emotion and cognition are not independent events; rather, they are interrelated functions working in concert. . . . The brain is continuously evaluating our internal and external environments based on previous experience, predicting what is likely to occur, and then determining the best course of action based upon this available data.”

I’m not sure it matters that there is no lizard brain part of our anatomy. It’s an excellent metaphor that helps us understand the ideas. It harkens back to Freud’s id, ego, superego, and Plato’s description of the tripartite soul of wisdom attempting to harness our spirit and appetite as one horse pulls in the direction of desire for physical gratification and the other for reputation and honour. Our wisdom has the task of keeping our chariot out of the ditch. These aren’t physical parts of the brain but drives or automatic reactions that we try to overcome to be better people. The idea of “lizard brain” is part of the vernacular now, used to explain the feeling when our emotions have control, and we’re on autopilot. Nonetheless, it would be preferable to make that clear.

Menakem’s explanation of the vagus nerve, which he calls the “soul nerve” is also disputable. He speaks glowingly of it:

“It is the largest organ in your body’s autonomic nervous system, which regulates all of your body’s basic functions. . . . When your heart sinks; when your spirit soars; or when your stomach turns in nausea–all of these involve your soul nerve. . . . In fact, one of the main purposes of your soul nerve is to receive flight, flee, or freeze messages from your lizard brain and spread them to the rest of your body. Another purpose is precisely the opposite: to receive and spread the message of it’s okay; you’re safe right now; you can relax. . . . Your soul nerve tells most of the muscles in your body when to constrict, when to release, when to move, and when to relax and settle” (138-140).

Polyvagal theory is highly contentious on its own (see here, here, and here), but this goes ever further to attribute a questionable amount to the workings of the vagus nerve. Again, the important takeaway is that our mind is not just in our skull, but significantly in our body.

Reading Menakem is like reading Epicurus, who sometimes gets close to our current understanding of atoms but isn’t quite there, but it doesn’t matter. What matters is that Epicurus’s understanding of the body being made of the smallest perceptible things that disperse after death, removing the possibility of an afterlife, aligns with his theory of death as inconsequential to our lives because we won’t be alive when it happens! We can work backwards from this conclusion about death to understand his thinking, but it’s not necessary to believe in his understanding of atoms to agree with him. Similarly, we can understand and agree with the theory Menakem ascribes to, that the body affects the mind, without the dubious ins and outs of how that might work.

The important part that makes perfect sense: “With practice, you can begin to consciously and deliberately relax your muscles, settle your body, and soothe yourself during difficult or high-stress situations. This will help you avoid reflexively sliding into a fight, flee, or freeze response in situations where such a response is unnecessary” (140). There are studies that show that simply exhaling for longer than inhaling for a few minutes each day can alleviate anxiety. But this is also the kind of message told to us as children when we were exploding with rage and mum or dad or a favourite teacher had us take a breath, count to ten, and try again.

We still need to be reminded to stop and think.

It’s frustratingly difficult to produce evidence of the efficacy of a therapeutic technique with so many variables to control for; however, when presented with the choice of allowing ourselves to be triggered and reactive in ways that haven’t been working for us or using these exercises to slow down and to think and respond to one another, this theory is clearly the better way if we hope to develop any social cohesion as we work through the looming difficulties ahead.