by Andrea Scrima

Sequel to the essay “Musings on Exile, Immigrants, Pre-Unification Berlin, Trauma, Naturalization, and a Native Tongue.”

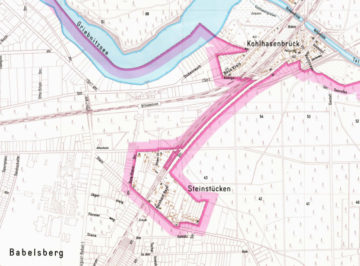

It’s disorienting when cities lose their gray zones—the undefined plots of fallow land that used to line the banks on the Brooklyn side of the East River, for instance, the nineteenth-century warehouses, docks, and quietly deteriorating, decommissioned refineries. Crumbling cement made porous by weather and weeds, the whole of it replaced now by faceless, blue-hued high-rise towers of glass and steel that sprang up like mutant mushrooms over the past decade and a half to block the path of the evening sun along the waterfront, erase the sharp glint of silvery light that once illuminated defunct railroad tracks at sundown, their perfectly parallel lines momentarily ablaze with the recollection of past importance. In Berlin, wasteland terrains could be found nearly everywhere before the Wall came down: the long stretch of a discontinued S-Bahn line that led from Monumentenstrasse and over the bridges at Yorckstrasse up to the former railway terminus Anhalter Bahnhof, now a ruin consisting of no more than a fragment of the once-massive building’s façade, where a semicircular set of overgrown train tracks opened onto the remains of a round loading dock. A decade and a half after Allied bombs had obliterated much of Germany, its division into two countries produced a haphazard border that sliced through the massive reconstruction project underway, blocking streets and cutting through buildings and canals and occasionally giving rise to little pockets of land connected to West Berlin by long roads flanked on either side by the Wall.

These are my cartographies of the past forty years, but if I go back farther, I remember that there were once empty lots and wooded areas on Staten Island, too; somewhere between New Dorp and Oakwood, an embankment path used to run alongside the borough’s one train line and led to a small candy store on Guyon Avenue, its dry packed dirt a red umber in the sunlit mental images of my childhood. My memory of these snatches of undeveloped land, long since leveled out for construction, are centered around loss: the loss of unplanned space, the loss of recollection when the locations that trigger memory no longer exist, the loss of freedom. Foundations were dug and housing settlements built and sewer systems laid in place, and the adventure these plots once promised, the respite from school and the all-pervading order of things—the type of daydreaming this world of non-rectilinear, flowing, organic space made possible—gradually disappeared.

I’d already been living in Berlin for several years when I found myself imagining random moments preceding my time there—a bus pulling away from a curb on a street where I would one day, twenty or thirty years later, live, a woman in a polka-dot dress pushing a perambulator—and then myself, four thousand miles away, at that very same moment, a girl crunching acorns under the heel of her shoe on her way home from school, with no notion of the invisible threads weaving their way toward a place I would later call home. New York had been the city of my parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, and I felt the accumulated loss of the time I hadn’t spent there. All at once everything would seem like some kind of terrible misunderstanding, and I’d have no idea why I’d stayed away so long, and for one disembodied moment I’d actually think I could change my mind and return to a point in the past in which I’d never left in the first place. But Berlin held a strange power over me, as though I were compelled to stay until I understood some part of what had happened here. The ghosts of Berlin’s past lived on in its odd cartographies, and those of us who came from elsewhere felt their presence most keenly.

I remember waking up one morning to a dark, rainy day; the lack of light in Berlin, even in spring, was something I’d grown resigned, but never really used to. The day before had been partly overcast, with wisps of cloud that rendered the light a pearly white so unlike the stark contrasts and saturated hues I’d grown up with. Today, it was as though the color had been drained from things; even the reds were flat and dull. But on these overcast, lightless days, there was one color that retained an eerie luminosity: the green of the moss growing on the trunks of trees and stone walls, which glowed even more intensely in the rain and fog, a hallucinatory green that seemed to radiate into the space around it, a magical green of fairies and elves and nymphs and dryads reveling in the one metaphysically potent color these geographic parts have to offer.

I recalled, many years ago, seeing an advertisement mural for a German company that specialized in painting building facades; it was four stories high and took up the entire side of a building. Part of the ad consisted in a sort of rainbow, the colors of which ranged from beige to mustard, rust, dull green, and brown. It was a palette of colors that appealed to a specifically German aesthetic sensibility, but it seemed to me at the time that it signified something sinister. I was hungry for color those first few years in Berlin, as though my brain were being deprived of something it required, like an essential nutrient. I was working as a freelance graphic designer, and one of my tasks was to create a series of images for the video conference service the German Federal Post (which in the mid-eighties included the telephone company) offered to corporate clients. The pictures appeared on the screen as a graphic image before the call was put through; they served to identify the location of the respective conference partner with the trademark post horn, city name, and a composite image of well-known landmarks and sites. When I presented the drafts in video conference calls that took place in a soundproof chamber inside the International Congress Center, one of the Bundespost managers complained that the palette I’d chosen—blues and reds and greens—was not subdued enough, not “dezent,” as he put it. Although I knew that the word did not mean the same as the English word “decent,” it nonetheless struck me: he found primary colors to be garish, indiscreet, I want to write “American,” but I’m not sure if my memory is playing tricks on me.

*

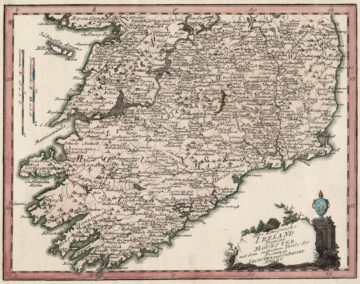

I had a book of maps with me on my first transatlantic flight, and as the plane approached land at dawn, I leafed through it, searching for the section that corresponded to the landscape creeping into view 35,000 feet below. The sun hadn’t yet appeared on the horizon, and the pre-dawn glow had transformed the waterways—all the winding rivers and tributaries and lakes—into liquid light, gleaming silvery squiggles that wound their way into the distance, like trails of mercury poured out onto the landscape. I studied one particular lineation, memorized its curves, and when I found it on the page before me, the same precise shape, a jolt of pleasure shot through my veins as I realized I was seeing Ireland for the very first time. But it was more than pleasure: it was like a kind of dissolution of boundaries between the self and the world, between the printed image and the reality on the ground. I was in unknown territory, but I had a key and could use it, and as I stared out the cabin window, the precise congruence between the image in the book on my lap and the actual topography far below—the product of centuries of surveying and mapmaking and the countless wars these efforts have been in service to—sent my mind into a spin.

I had a book of maps with me on my first transatlantic flight, and as the plane approached land at dawn, I leafed through it, searching for the section that corresponded to the landscape creeping into view 35,000 feet below. The sun hadn’t yet appeared on the horizon, and the pre-dawn glow had transformed the waterways—all the winding rivers and tributaries and lakes—into liquid light, gleaming silvery squiggles that wound their way into the distance, like trails of mercury poured out onto the landscape. I studied one particular lineation, memorized its curves, and when I found it on the page before me, the same precise shape, a jolt of pleasure shot through my veins as I realized I was seeing Ireland for the very first time. But it was more than pleasure: it was like a kind of dissolution of boundaries between the self and the world, between the printed image and the reality on the ground. I was in unknown territory, but I had a key and could use it, and as I stared out the cabin window, the precise congruence between the image in the book on my lap and the actual topography far below—the product of centuries of surveying and mapmaking and the countless wars these efforts have been in service to—sent my mind into a spin.

The notion that the smartphone has rendered paper maps, books, and diaries obsolete bears closer examination. In Rome recently, I carried an old Michelin guide around with me that I’d bought in 1986, on my first visit to the city. Of all the churches and ruins we were planning to see, I reasoned, not much will have changed in the past 33 years. The book contains a wealth of historical information far more detailed than Wikipedia, and nearly no images. But I nonetheless managed to miss the fact that we were living around the corner from Forte Bravetta, the site of hundreds of executions during the years of Italian fascism and German occupation, where the partisan priest Giuseppe Morosini blessed the firing squad preparing to kill him by not whispering, as Rossellini depicted the scene in Roma, città aperta, but crying out loud in the words of Jesus: “God forgive them: they know not what they are doing,” after which ten of the twelve soldiers shot into the air and the German commanding officer had to carry out the execution of the wounded priest himself, as his men were evidently unwilling to burden their souls with the sin of murdering a man of God.

The West German Self-Regulatory Body of the Movie Industry (Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft, or FSK) deemed the film a “rabble-rousing” danger to postwar audiences and banned it in the interest of a “European understanding among nations” until 1960, when it was allowed into cinemas—albeit with a note added to the opening credits explaining that the film was not directed against German soldiers or the German people; that the Wehrmacht had already, at the point Rome had been declared an open city, withdrawn; that the SS had, however, remained behind as an illegitimate police force and had exploited their power; and that the Roman resistance had engaged in deliberate terrorist acts of its own. It would take Germany nearly another twenty years to begin to seriously address its collective guilt and complicity in the Nazi genocide of European Jewry, a process incidentally unleashed by the West German broadcast of the American TV mini-series “Holocaust.” It was the first of its kind to exert a profound emotional impact on a large number of German viewers, who found themselves unexpectedly identifying with the acculturated German Jewish family it portrayed. The series, aired in 1979, garnered ratings as high as 41% and marked the beginning of a process of introspection known in Germany as “memory culture.” The message hit home that it was in large part ordinary Germans’ passive acceptance, in other words, that they’d done nothing to prevent the persecution of Jews, which enabled the Nazis to press on with the Final Solution. Later that year, it induced the West German parliament to lift the statute of limitations on war crimes.

By the time I arrived in Berlin—the war lay nearly forty years in the past, but it was only five years since the mini-series had run—my twenty-three-year-old American mind believed that West Germany had come to terms with its fascist legacy. As I learned the language and gradually grew acquainted with the culture, however, the war became increasingly palpable, as though it had happened in a more recent past. Indeed, it continued to claim lives: Blindgänger, undetonated bombs and ordnance from WWII, an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 tons of which still lie buried underground to this day, regularly resurfaced in construction sites and occasionally exploded, leading to casualties. I only recently listened to the speech Bundestag President Philipp Jenninger held before the West German Parliament in 1988 to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of the November Pogroms. It was a surprisingly thorough, in-depth historical and psychological analysis of German anti-Semitism, the fascist psyche, and the mindset of the German majority that had allowed the atrocities to occur. The speech drew widespread criticism and Jenninger felt compelled to resign the next day, not because the speech itself was in any way counterfactual or intrinsically reprehensible, but because the way in which it was interpreted led fifty indignant parliamentarians to storm out in protest. Jenninger’s fall from grace would stigmatize the text permanently, even though, one year later, German Jewish leader Ignatz Bubis quoted from it liberally in his own speech to general approval—without attribution, in all likelihood to test the audience’s reaction and to demonstrate the glaring contradiction between the overwhelmingly negative response to Jenninger’s sober reflections on German culpability and the public acceptance of the very same words when spoken by a Jew. The scandal of the text, it was said, lay in Jenninger’s bland rhetorical delivery, formulating the anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda in free indirect speech and asking, for instance, if the Jews hadn’t gone too far in laying claim to things they had no legitimate right to: wasn’t it time limitations were imposed on them? Hadn’t they deserved to be put in their place? And if you ignored the bombast and excess, wasn’t there a kernel of truth in all the propaganda leveled against them? Much has been written about Jenninger’s monotonous reading voice as the culprit—that, had he been able to vocalize better, the text would have been understood the way it was intended. To every outside observer, however, the real scandal was that anyone could confuse Jenninger’s own position, which he stated clearly at the beginning of and repeatedly throughout his speech, with the examples of anti-Semitic thinking the speech reflected on. Jenninger made it all too clear how perfectly in accord with the Führer much of the populace had been; that it had not been overpowered by a despot who had seized control and put into action murderous policies against their will or even against their knowledge, but that Hitler’s rise to power had led to a “spirit of optimism and self-confidence” in the German people. The prosperity Nazism brought to Germans avenged the humiliation they’d experienced after the end of WWI and Versailles and rectified the chaos of the Weimar era, which stood not only for mass inflation, unemployment, and political infighting, but for a high degree of German Jewish emancipation, assimilation, success in industry and banking, and intellectual achievement in the sciences and humanities—all of which increasingly became the target of spite and envy.

This was the taboo: Germany was prepared to remember and to memorialize, was prepared to claim “Never again” and to warn future generations of the dangers of fascism, but it was not prepared to admit that Hitler had enjoyed widespread and even fanatical support across the country; that the German civilians who had not taken part in the excesses of Kristallnacht had nonetheless passively allowed the crimes to occur and offered no real resistance and no help to their fellow Jewish citizens. Several days after Jenninger resigned, he remarked that there were certain things it was still not possible to say in Germany. When Michael Fürst, deputy leader of Germany’s Central Council of Jews, spoke out in full support of the speech, he was also forced to resign. The very accusation that the audience could not tell between Jenninger speaking in his own voice and speaking as one of the Nazi sympathizers of the time is telling: how could the two be confused, as Jenninger made his principles abundantly clear? Did the shock consist in a mirroring effect, an unwelcome encounter with a long-denied psychological truth? It’s one of the paradoxes of human behavior that the exposure of something shameful leads to aggression rather than an awareness or admission of guilt. The enduring taboo of the average German’s moral ambivalence might very well have echoed too closely some of the parliamentarians’ own personal experiences of the time, and it was this confrontation with the past, stripped of the pieties that had masked it, not least from those concerned, that was so unacceptable.

*

Three years ago, following another eighteen months of waiting for my application for German citizenship to be processed, the very nice Russian-German Frau I. at the Einbürgerungsamt, after having me sign various documents and filling out whatever else still needed to be filled out and stamping various pages and stapling things together, after reciting the oath in easy-to-remember portions and waiting for me to repeat each one before continuing, said, behind her mask, that the moment she handed me the certificate she was presently holding in her hands would be the moment I became a German citizen. I was surprisingly moved. Frau I. had replaced the former clerk I’d been assigned to, Herr. H., following his unexpected passing; if he’d still been alive, I don’t think he would have allowed me to attain citizenship. I’d been living in Germany for well over thirty years; I’d brought my son up here. There’d been bouts of reluctance along the way to commit to remaining in the long term, and yet I’d chosen to stay. Frau I. had an instinct for the solemnity of the occasion, and for the emotions involved, which were, she knew, likely mixed, and I was grateful that she understood and that she was giving me a moment to pause and fully absorb this little ceremony instead of simply sliding the papers across the desk and wishing me a good day.

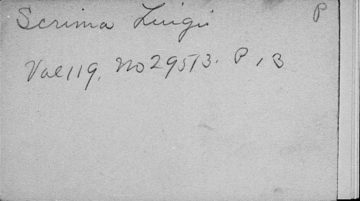

But what did I feel? I was now a German citizen, a dual national. I could come and go as I pleased, I was no longer beholden to a certificate of permanent residency glued into a passport that could be lost or stolen. But it was really EU citizenship I was after, I told myself, and it almost sounded like an excuse, as though being or becoming German were still, after all these years, something somehow dubious. How had my grandfather Luigi felt, I wondered, at becoming a naturalized American citizen; was there an unaccountable sense of disappointment, did he get cold feet, was he seized with the irrational urge to run away, flee into his past, return to his home and his native language, to Greci? What does it mean when years of cultural assimilation do nothing to quiet these inner longings?

But what did I feel? I was now a German citizen, a dual national. I could come and go as I pleased, I was no longer beholden to a certificate of permanent residency glued into a passport that could be lost or stolen. But it was really EU citizenship I was after, I told myself, and it almost sounded like an excuse, as though being or becoming German were still, after all these years, something somehow dubious. How had my grandfather Luigi felt, I wondered, at becoming a naturalized American citizen; was there an unaccountable sense of disappointment, did he get cold feet, was he seized with the irrational urge to run away, flee into his past, return to his home and his native language, to Greci? What does it mean when years of cultural assimilation do nothing to quiet these inner longings?

The large swathes of fallow land in Berlin have largely disappeared, and while traces remain, their power to evoke the past is diminishing. The endurance of ruins, of interstices in the order of things, is a visible testimony to every political order’s temporariness: this is their importance. And in these ruins, among the ivy and overgrown shrubs, live all the gnomes and gremlins and sprites and dwarves, radiating in a mossy green, the one color of the German rainbow to achieve an otherworldly luminosity.