by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Ten years have passed since I left Japan. And it has been about five years since I stepped away from professional translation. I have made little effort to retain my Japanese, and so it has hardly been surprising to find my language skills falling away. There have been times where I even took a willful enjoyment realizing just how fast all those years of hard work could fade away. Like a colorful mandala made of sand that Tibetan monks labored to create and then destroy, my ability to write in Japanese disappeared overnight.

The more passive pursuits of reading and listening have proven to be less slippery. But I no longer have that feeling of being a different person in thinking and dreaming in Japanese. It’s gone. And my son, who learned Japanese as his native language, lost his skills even faster than I did. People sometimes say to me that a person can’t lose their native language, but it’s simply not true. I have met people who lost their first tongues time and time again. My son, who left Japan at seven years old, might have Japanese in their somewhere, but it is buried deep.

Effortless to learn, it’s also easy to lose languages in childhood.

In contrast, to learn a second language as an adult is a Herculean undertaking. Neither quick nor easy, it took me a decade of serious study to feel confident in Japanese.

Last week, Claire Chambers wrote a marvelous essay in these pages called Beginning Hindi with a Beginner’s Mind. By sheer coincidence, her essay mentioned a memoir that I am currently reading called Dreaming in Hindi. Written by Katherine Russell Rich, it is about the author’s year of language study in the romantic desert city of Udaipur.

Both Chambers and Rich write of how daunting it is to learn a language later in life. To try and speak a tongue as different from English as Hindi is to become vulnerable. Childlike. There is little to hold onto, so the unfamiliar language feels slippery, even treacherous. It is endlessly humbling—sometimes even humiliating to try and make oneself understood.

Amidst the self-doubt and confusion, Chambers recalls the Japanese Zen Buddhist idea of shoshin, or the beginner’s mind and heart.

She writes:

This idea suggests that the more expert and technically skilled a person is, the less creative they may become. Immersed in a field, their mind can get institutionalized, and interesting pathways are then closed off. Becoming a newly-hatched student again entails the asking of basic but meaningful first-principle questions in a way that can be illuminating.

I wonder if there is a better way to gain critical distance from one’s pre-conceived notions and habitual ways of thinking than escaping the confines of one’s language? …For as Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

Michael Pollan, in his book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence persuasively argues that as we grow older, our minds more and more fall into mental ruts as the ego takes over completely. He says that what we refer to as the ego is a short-hand for the “default mode network” in the brain. This is something that is not developed fully in children or other animals. But in adulthood, it becomes the “boss” of our brains and is something connected to our sense of self, or ego.

Michael Pollan, in his book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence persuasively argues that as we grow older, our minds more and more fall into mental ruts as the ego takes over completely. He says that what we refer to as the ego is a short-hand for the “default mode network” in the brain. This is something that is not developed fully in children or other animals. But in adulthood, it becomes the “boss” of our brains and is something connected to our sense of self, or ego.

Reading Chambers’ essay, I wondered if the beginner’s mind of an adult language learner doesn’t somehow disrupt our default mode network in a similar way- becoming a very healthy choice—like learning to play an instrument as an adult– for exercising the mind.

The subject is not fully understood, but it does seem that we neurologically processes second languages in a different way and in a different part of the brain than we do our first language. This is why there have been cases of people only losing one language in a stroke. It is also why third and fourth languages are easier for bilinguals. You are literally re-wiring your brain. And that is why I have always felt comfortable saying I am a different person in Japanese.

2.

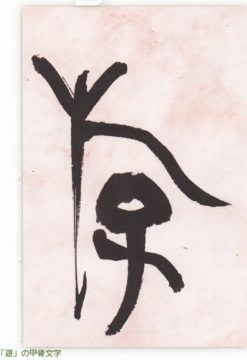

Before Japan, I studied French in high school and college, so I was not a stranger to making vocabulary lists. But Japanese would be challenging. That had been obvious on the bus ride into Tokyo from Narita Airport on my first night, seeing all the neon signs sizzling in Chinese characters. In Japan, the Chinese characters are known as kanji, which means “Han characters.” In addition to kanji, Japanese makes use of two other writing systems: hiragana and katakana. Both are phonetic-based syllabary systems.

Japan is unique in the world in utilizing three different writing systems. And it certainly made matters daunting in the beginning.

The U.S government categorizes the languages it teaches to its foreign service personnel based on the number of hours it takes to attain “professional working proficiency” –something that prioritizes speaking and reading, the more passive aspects of language learning. The most challenging for English speakers are known as Category IV languages. These are Arabic, Korean, Cantonese, Mandarin, and Japanese. Languages in this group are exceptionally difficult requiring eighty-eight weeks. In contrast, a Category I language, like Spanish, takes twenty-four weeks.

In discussing her initial challenges with Hindi, Chambers gives some examples:

It is highly gendered, like many European tongues but unlike English. In common with German, it is a Subject-Object-Verb or SOV language. Accordingly, I found myself struggling once more with (to SVO ears) the way the action seems delayed until the end of the sentence or at least the grammatical clause.

This really caught my attention since it is one of my favorite aspects of speaking Japanese. I love thinking in SOV. I could never explain why I love this except that with the action coming at the end of the sentence it always seemed to keep the punchline one step beyond. And it is easier for me to be funny in Japanese. Is it because I am happier and more at ease? Or is it just that having the verbs come at the end keeps the fun going? In Japanese, it is also grammatically permissible to move the parts of the sentence around, so while Japanese is a SOV language, you can put the subject or noun at the end for emphasis, thereby opening many more possibilities for expression.

In one of my all-time favorite books about Japanese, Making Sense of Japanese: What the Textbooks Don’t Tell You, by Haruki Murakami’s translator, the great Jay Rubin has a great example of the fun that can be had with SOV:

Some writers, such as Kabuki playwrights, have capitalized on the perverse placement of the verb at the end. The theater is charged with suspense as the retainer, center stage, slowly, tantalizingly intones the lines, “As to the question…of whether or not this severed head…is the head of my liege lord, the mighty general Kajimura Saburō Mitsumaru…known throughout the land for his brilliant military exploits…beloved by the people of his domain for his benevolence towards even the lowliest farmer…I can say, here and now, without a single doubt clouding my mind…that although the throngs gathered here before us may wish the truth to be otherwise…and the happiness of his entire family hangs in the balance…this my master’s head…is…NOT!

3.

3.

Over the years, I met fellow students who tackled the gargantuan project of studying Japanese by simply throwing aside one aspect of the language to better learn on the rest. I have met, for example, people who refuse to study kanji. This is because they want to focus on verbal communication. And maybe reading. Memorizing how to write kanji requires too much time and energy and will, it is true, suck all the oxygen out of the room. Learning to read it is infinitely easier… but as my early teachers repeatedly told me when I tried to get out of my writing practice, if I didn’t learn to write it, my reading would always be shaky.

I also met people who flat-out neglected the polite and humble forms. These are usually more bookish students who will be able to recognize them in reading but don’t want to spend the enormous amount of study required to master it in real situations.

And here we arrive at the crux of what in my opinion makes Japanese so damn hard.

Japanese has an elaborate system of honorifics called keigo (literally “respectful language”). Unlike in English, keigo goes beyond vocabulary choices involving the conjugation of verbs –and its use is mandatory in many social situations. For example, when I studied tea ceremony, I had to be careful to at least try and get it right. So much of my Japanese practice involved me listening to my Japanese husband speak. And therein lie the trouble since he used different pronouns and different verbs than I was permitted to use in the tearoom. Thoughts would pop into my head in Japanese. Buy alas, it was often in the wrong Japanese.

I have read that Arabic, another Category IV language, also has grammatically distinct high and low literary and colloquial tongues. But I never realized how complicated it was until I read Zora O’Neill’s fantastic book All Strangers Are Kin: Adventures in Arabic and the Arab World, about her brave attempt to go beyond textbook Arabic and learn the language as it is really spoken in Egypt, the Gulf, Lebanon, and Morocco.

It’s quite a ride.

Because Japanese often drops pronouns altogether and uses keigo forms to convey subject (since one would only use honorifics about other people and humble form for oneself), it is important to have a basic understanding of it, even if you are always putting your foot in your mouth when you try to use it in actual conversations.

As Jay Rubin explained, when Japanese people say,

Honjitsu wa yasumasete itadakimasu. (Today, humbly receiving the day off), the best translation for that is: Gone Fishin’

Two verbs. No subjects, no objects, no agents, nobody. And the honjitsu wa tells us only that these two incredible verbs are happening “today.”

Sound like the twilight zone?

4.

4.

Compared to the above, I always thought the writing system was straight-forward. At most, it was only an initial challenge.

One of the most interesting parts of Rich’s book about Hindi was her discussion with experts about the way writing and speaking are so different for language learners. While attaining native ability of a language is impossible after a certain age, writing a different script is not as age-sensitive. Non-natives can become very good at writing characters.

Experts told Rich that a person can be dyslexic in one language but not another.

In one of the symposiums she attends in Canada, she is told that a research team has uncovered a Chinese region in the brain, “an area in the left middle frontal gyrus that lights up when people read Chinese but not English—and gets lit even when someone’s grasp of Chinese is limited to a few weeks’ lessons.”

It is true that when I read in Japanese—especially in kanji-rich texts—I am not reading as much as looking. You can understand meaning without sounding out the words and processing the meaning. Being more pictorial, the general idea can sometimes be grasped instantaneously. For me, it made reading in Japanese tremendously enjoyable. According to the experts Rich talked to, while English engages mostly the left side of the brain, with Chinese both hemispheres are activated.

Somehow the Japanese language, maddeningly simple in structure but complex in meaning, light and lovely in the ear and mouth, with it’s beautiful characters and rich seasonal vocabulary, reflects the people’s appreciation for the beauty and poetry of everyday life, the deeply observed passing of the seasons, and the variety and solace found in the natural world. Of course, it is possible to do all of the above in English, as it is possible in any language, but speaking in Japanese lent itself perfectly to these things.

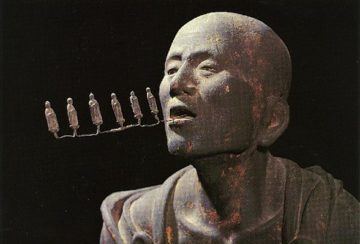

In Chambers’ next essay, she is planning to discuss the ways in which language shapes her thoughts and alters her worldview in Hindi and in Urdu. In classical Chinese translator David Hinton’s book Hunger Mountain, he writes:

I’ve been translating classical Chinese poetry for many years and slowly over those years I’ve come to realize that in translation, I’ve stumbled upon a way to think outside the limitations not just of the mainstream Western intellectual tradition, but also of my own identity, a way to speak in the voice of ancient China’s sage masters, and for them to speak in mine.

What a wonderful dialogue across time and space.

What a wonderful dialogue across time and space.

In Zen literature, there is a recurring motif of an empty-mirror mind. As David Hinton says in his new book, China Root, “When thought stops, that moment of awakening, we are wholly present in life as moment-by-moment experience of incandescent perceptual immediacy.” This is something related to the Zen Beginner’s Mind. To stand fully present in the moment looking out at the world with mirror-deep eyes. Now that is clarity to strive for!

In the same way that the Japanese worldview was embedded in the language itself, I imagine the languages of cultures long past would open more archaic and timeless ways of being in the world. Think of all the metaphysical vocabulary in Sanskrit or the way Ann Patty in her memoir, Living with a Dead Language: My Romance with Latin describes reading ancient Roman poetry with its concepts of empire and paganism. Like learning a stringed instrument, the older one gets the more challenging language learning becomes, and Ann Patty decides to stay mentally fit by taking up Latin at the age of 57. Language learning, she concedes, is an activity for young people with their more plastic minds….. and yet, the allure of this idea of the existence, in various languages, of different versions of ourselves, remains strong.

For Claire

+++

For more about Japan, please visit my Dreaming in Japanese Substack

To read

Claire Chambers’ Beginning Hindi With A Beginner’s Mind

Katherine Russell Rich’s Dreaming in Hindi

Zora O’Neill’s All Strangers Are Kin: Adventures in Arabic and the Arab World

Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence

Ann Patty’s Living with a Dead Language: My Romance with Latin