by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

I write this on a winter day in California. It is Mirza’s two hundred and twenty first birth anniversary. There is a nip in the air and the sunlight is filtered through my carob tree; my notes, scribbled in Nastaliq, are dappled and illuminated by sudden flashes as the branches sway. Isn’t Ghalib’s Delhi a labyrinth of dappled alleys, a dream leaping from rooftop to rooftop, getting a stealthy taste of the saffron-cream dessert known to be prepared here under a full moon and left overnight to set in winter dew— a heady mix of in-the moment-sensations that vivify memory— rising with the city’s nimble frangipani, its famed red sandstone and marble minarets, returning reliably like its homing pigeons.

Watching an Indian film that revolves around Mughalai cuisine, my husband remarks that it makes him nostalgic for a place he knows without ever having visited; the culture is in our bones, being Pakistanis whose grandparents migrated from India to Pakistan around the time of partition. As a student in Lahore, I loved viewing the silhouettes of Mughal buildings at night and in the winter fog, the contours of the poet Iqbal’s home and burial place in the glimmer of the street vendors’ lanterns deep in the walled city. On recent visits, I see mustard fields blooming in winter sunshine, my brother’s orchards and fields luxuriating in the most delectable shades of green. Only a few miles away from his farm, lies the “No Man’s Land”— not much bigger than a cricket pitch— beyond that lies India.

I have often stood by the gate of flags at the Barki border, gazing at the distant rice paddies and colorful turbans of India, reflecting on what brings the two countries together, what keeps them apart.

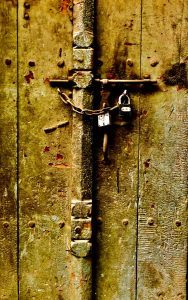

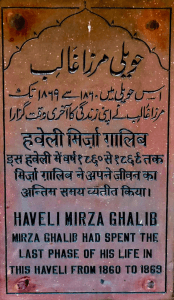

And here, now, a cup of chai beside me on an octagonal table that my mother brought me from Lahore, I’m chewing on pods of cardamom, and leaning on velvet bolster cushions as I write, the kind that Mirza must have used, reclining on his “takht” (which refers to a simple wooden cot or light bedstead). I have, before me, a set of lyrical photos of Old Delhi— taken by the illustrious Indian poet Sudeep Sen who happens to be a brilliant photographer too. These doors belong to the heart of Delhi, Mirza Ghalib’s neighborhood; these are aged thresholds that have seen many tearful departures and arrivals; eyes, old and young, have peeped through them and waited for a loved one’s footfall.

And here, now, a cup of chai beside me on an octagonal table that my mother brought me from Lahore, I’m chewing on pods of cardamom, and leaning on velvet bolster cushions as I write, the kind that Mirza must have used, reclining on his “takht” (which refers to a simple wooden cot or light bedstead). I have, before me, a set of lyrical photos of Old Delhi— taken by the illustrious Indian poet Sudeep Sen who happens to be a brilliant photographer too. These doors belong to the heart of Delhi, Mirza Ghalib’s neighborhood; these are aged thresholds that have seen many tearful departures and arrivals; eyes, old and young, have peeped through them and waited for a loved one’s footfall.

Ghalib saw Delhi suffer unspeakable calamities after the war of 1857, known as the Mutiny or the war of independence, depending on whether you’re on the side of the British Raj or the people of the Indian subcontinent. As the city fell, Ghalib wrote about it in bitterness, and bemoaned the sorrows of the city-dwellers more than the city’s physical devastations or imperial status. He had already said goodbye to its culture, but forever the Urdu poet wedded to the elusive beloved, he preserves for himself and for us the transcendental promise of love, its power and pluck:

dil hī to hai siyāsat-e-darbāñ se Dar gayā

maiñ aurjā.ūñ dar se tire bin sadā kiye

Merely a timid heart, it was frightened of the politics of the doorkeeper

Would I ever leave your door without calling out for you?

Photo Credit: Sudeep Sen