Category: Recommended Reading

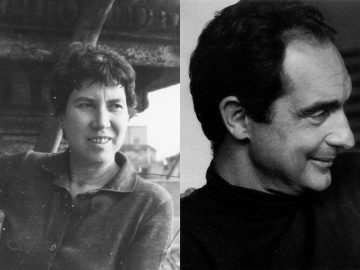

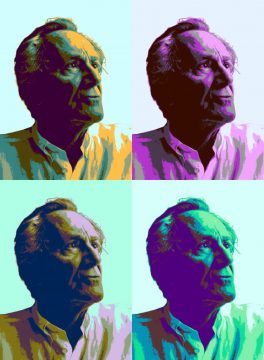

Writing Beckett’s Letters

George Craig at Music & Literature:

Between 1948 and 1952 there took place a particularly remarkable correspondence: that between Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit. In the course of his life Beckett wrote something approaching 20,000 letters. Fascinating as many of these are, they offer nothing that can match this explosion of words. But then Duthuit was not just any correspondent: he was a highly cultured and intellectually rigorous art historian and critic, with total confidence in his own judgement. For Beckett, recognising these qualities and drawn by Duthuit’s impatient refusal of cultural orthodoxies, he represented something close to an ideal interlocutor: someone to whom, in the areas that mattered, anything could be said.

Between 1948 and 1952 there took place a particularly remarkable correspondence: that between Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit. In the course of his life Beckett wrote something approaching 20,000 letters. Fascinating as many of these are, they offer nothing that can match this explosion of words. But then Duthuit was not just any correspondent: he was a highly cultured and intellectually rigorous art historian and critic, with total confidence in his own judgement. For Beckett, recognising these qualities and drawn by Duthuit’s impatient refusal of cultural orthodoxies, he represented something close to an ideal interlocutor: someone to whom, in the areas that mattered, anything could be said.

These voluminous letters are in French. Beckett’s years in France – at first in Paris before the War, then, during the Occupation, in hiding in the South, finally, after the Liberation, back in Paris – were a time during which, slowly at first but with increasing urgency, the move to writing in French took shape. The risks were huge, but by the mid-1940s the impulsion was irresistible. It issued in two bodies of writing: the early stories and Molloy; and the letters.

more here.

What Lurks Beneath Henry James’s Style

Colm Tóibín at Bookforum:

Henry James did not wish to be known by his readers. He remained oddly absent in his fiction. He did not dramatize his own opinions or offer aphorisms about life, as George Eliot, a novelist whom James followed closely, did. Instead, he worked intensely on his characters, offering their consciousness and motives a great deal of nuance and detail and ambiguity.

Henry James did not wish to be known by his readers. He remained oddly absent in his fiction. He did not dramatize his own opinions or offer aphorisms about life, as George Eliot, a novelist whom James followed closely, did. Instead, he worked intensely on his characters, offering their consciousness and motives a great deal of nuance and detail and ambiguity.

James was concerned with his privacy, burning many of the letters he received. Most of the time, he conducted his own correspondence with caution and care. But at the end of the nineteenth century and in the early years of the twentieth, when James was in his late fifties and early sixties, he began to write letters to younger men whose tone had a mixture of open affection and something that is more difficult to define.

more here.

Calvino on Ginzburg

Italo Calvino at The Paris Review:

Natalia Ginzburg is the last woman left on earth. The rest are all men—even the female forms that can be seen moving about belong, ultimately, to this man’s world. A world where men make the decisions, the choices, take action. Ginzburg, or rather the disillusioned heroines who stand in for her, is alone, on the outside. There are generations and generations of women who have done nothing but wait and obey; wait to be loved, to get married, to become mothers, to be betrayed. So it is for her heroines.

Natalia Ginzburg is the last woman left on earth. The rest are all men—even the female forms that can be seen moving about belong, ultimately, to this man’s world. A world where men make the decisions, the choices, take action. Ginzburg, or rather the disillusioned heroines who stand in for her, is alone, on the outside. There are generations and generations of women who have done nothing but wait and obey; wait to be loved, to get married, to become mothers, to be betrayed. So it is for her heroines.

Ginzburg comes an outsider to a world in which only the most conventional signs, tracing from an ancient era, can be deciphered. From emptiness there emerges, here and there, an identifiable object, a familiar object: buttons, or a pipe. Human beings exist only according to schematic representations of the concrete: hair, mustache, glasses. You can say the same about the emotions and behaviors; they reveal nothing. She doesn’t reveal so much as identify already-established words or situations: Ah ha, I must be in love … This feeling must be jealousy … Or, now, like in The Dry Heart, I will take this gun and kill him.

more here.

To Be More Creative, Cheer Up

Kirsten Weir in Nautilus:

I’m intrigued. Is creativity a skill I can beef up like a weak muscle? Absolutely, says Mark Runco, a cognitive psychologist who studies creativity at the University of Georgia, Athens. “Everybody has creative potential, and most of us have quite a bit of room for growth,” he says. “That doesn’t mean anybody can be Picasso or Einstein, but it does mean we can all learn to be more creative.” After all, creativity may be the key to Homo sapiens’ success. As a society, we dreamed up stone tools, the combustion engine, and all the things in the SkyMall catalog. “Our species is not fast. We’re not terribly strong. We can’t camouflage ourselves,” Puccio told me when we spoke on the phone. “What we do have is the ability to imagine and create new possibilities.” Creativity is certainly a buzzword these days. Amazon lists more than 6,000 self-help titles devoted to the subject. A handful of universities now offer master’s degrees in creativity, and a growing number of schools offer an undergraduate minor in creative thinking. “We’ve moved beyond the industrial economy and the knowledge economy. We’re now in the innovation economy,” Puccio says. “Creativity is a necessary skill to be successful in the work world. It’s not a luxury anymore to be creative. It’s an absolute necessity.”

I’m intrigued. Is creativity a skill I can beef up like a weak muscle? Absolutely, says Mark Runco, a cognitive psychologist who studies creativity at the University of Georgia, Athens. “Everybody has creative potential, and most of us have quite a bit of room for growth,” he says. “That doesn’t mean anybody can be Picasso or Einstein, but it does mean we can all learn to be more creative.” After all, creativity may be the key to Homo sapiens’ success. As a society, we dreamed up stone tools, the combustion engine, and all the things in the SkyMall catalog. “Our species is not fast. We’re not terribly strong. We can’t camouflage ourselves,” Puccio told me when we spoke on the phone. “What we do have is the ability to imagine and create new possibilities.” Creativity is certainly a buzzword these days. Amazon lists more than 6,000 self-help titles devoted to the subject. A handful of universities now offer master’s degrees in creativity, and a growing number of schools offer an undergraduate minor in creative thinking. “We’ve moved beyond the industrial economy and the knowledge economy. We’re now in the innovation economy,” Puccio says. “Creativity is a necessary skill to be successful in the work world. It’s not a luxury anymore to be creative. It’s an absolute necessity.”

But can you really teach yourself to be creative? A study published in the Creativity Research Journalin 2004 reviewed 70 studies and concluded that creativity training is effective. But it wasn’t entirely clear how it worked, or which tactics were most effective. More recent studies, however, take us inside the brain to tap the source of our creative juices, and in the process upend longstanding myths about what it takes to be Hemingway or Picasso.

Some of the earliest scientific studies of creativity focused on personality. And some evidence suggests that innovation comes easier to people with certain personality types. A 1998 review of dozens of creativity studies found that overall, creative people tend to be more driven, impulsive, and self-confident. They also tend to be less conventional and conscientious. Above all, though, two personality traits tend to show up again and again among innovative thinkers. Unsurprisingly, openness to new ideas is one. The other? Disagreeableness.

More here.

No Sympathy for Racists, No Matter What Their Age

Jessica Valenti in Medium:

This week, racists marched through the streets of Orlando, flashing white power symbols in advance of a Donald Trump rally; the Democratic presidential frontrunner bragged about his ability to hobnob with segregationists; Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the U.S. doesn’t need reparations because “we’ve” made up for slavery by electing a black president; and a political debate erupted over what exactly constitutes a concentration camp. And so, in the midst of what feels like pride week for bigots, I find it difficult to muster empathy for Kyle Kashuv, the Parkland-shooting-survivor-turned-conservative-activist, whose admission to Harvard was rescinded after violently racist comments he made in 2016 resurfaced. In this time of emboldened racism, we need schools, employers, clubs, and everyone else to send a clear message about what kind of behavior our society values, and what we find intolerable. The language Kashuv used is about as intolerable as it gets.

This week, racists marched through the streets of Orlando, flashing white power symbols in advance of a Donald Trump rally; the Democratic presidential frontrunner bragged about his ability to hobnob with segregationists; Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the U.S. doesn’t need reparations because “we’ve” made up for slavery by electing a black president; and a political debate erupted over what exactly constitutes a concentration camp. And so, in the midst of what feels like pride week for bigots, I find it difficult to muster empathy for Kyle Kashuv, the Parkland-shooting-survivor-turned-conservative-activist, whose admission to Harvard was rescinded after violently racist comments he made in 2016 resurfaced. In this time of emboldened racism, we need schools, employers, clubs, and everyone else to send a clear message about what kind of behavior our society values, and what we find intolerable. The language Kashuv used is about as intolerable as it gets.

Prominent conservatives have argued that Kashuv shouldn’t be punished for something he said when he was 16-years-old. (Although what is college admission if not a judgment of who you are at 16?) More disturbingly, they argued that expecting young white people to not use racial slurs is an unreasonable standard of behavior. Conservative podcast host Ben Shapiro, for example, tweeted that Harvard’s decision “sets up an insane, cruel standard that no one can possibly meet.” No one? Really?

More here.

Thursday, June 20, 2019

Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think

Arthur C. Brooks in The Atlantic:

The field of “happiness studies” has boomed over the past two decades, and a consensus has developed about well-being as we advance through life. In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s. Nothing about this pattern is set in stone, of course. But the data seem eerily consistent with my experience: My 40s and early 50s were not an especially happy period of my life, notwithstanding my professional fortunes.

The field of “happiness studies” has boomed over the past two decades, and a consensus has developed about well-being as we advance through life. In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s. Nothing about this pattern is set in stone, of course. But the data seem eerily consistent with my experience: My 40s and early 50s were not an especially happy period of my life, notwithstanding my professional fortunes.

So what can people expect after that, based on the data? The news is mixed. Almost all studies of happiness over the life span show that, in wealthier countries, most people’s contentment starts to increase again in their 50s, until age 70 or so. That is where things get less predictable, however. After 70, some people stay steady in happiness; others get happier until death. Others—men in particular—see their happiness plummet. Indeed, depression and suicide rates for men increase after age 75.

More here.

The hidden structure of the periodic system

From Phys.org:

The periodic table of elements that most chemistry books depict is only one special case. This tabular overview of the chemical elements, which goes back to Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer and the approaches of other chemists to organize the elements, involve different forms of representation of a hidden structure of the chemical elements. This is the conclusion reached by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig and the University of Leipzig in a recent paper. The mathematical approach of the Leipzig scientists is very general and can provide many different periodic systems depending on the principle of order and classification—not only for chemistry, but also for many other fields of knowledge.

The periodic table of elements that most chemistry books depict is only one special case. This tabular overview of the chemical elements, which goes back to Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer and the approaches of other chemists to organize the elements, involve different forms of representation of a hidden structure of the chemical elements. This is the conclusion reached by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig and the University of Leipzig in a recent paper. The mathematical approach of the Leipzig scientists is very general and can provide many different periodic systems depending on the principle of order and classification—not only for chemistry, but also for many other fields of knowledge.

It is an icon of natural science and hangs in most chemistry classrooms: the periodic table of elements, which is celebrating its 150th birthday this year. The tabular overview is closely linked to Dmitri Mendeleev and Lothar Meyer—two researchers who, in the 1860s, created an arrangement of elements based on their atomic masses and similarities.

More here. [Thanks to Farrukh Azfar.]

A radical legal ideology nurtured our era of economic inequality

Sanjukta Paul in Aeon:

There does economic power come from? Does it exist independently of the law? It seems obvious, even undeniable, that the answer is no. Law creates, defines and enforces property rights. Law enforces private contracts. It charters corporations and shields investors from liability. Law declares illegal certain contracts of economic cooperation between separate individuals – which it calls ‘price-fixing’ – but declares economically equivalent activity legal when it takes place within a business firm or is controlled by one.

There does economic power come from? Does it exist independently of the law? It seems obvious, even undeniable, that the answer is no. Law creates, defines and enforces property rights. Law enforces private contracts. It charters corporations and shields investors from liability. Law declares illegal certain contracts of economic cooperation between separate individuals – which it calls ‘price-fixing’ – but declares economically equivalent activity legal when it takes place within a business firm or is controlled by one.

Each one of these is a choice made by the law, on behalf of the public as a whole. Each of them creates or maintains someone’s economic power, and often undermines someone else’s. Each also plays a role in maintaining a particular distribution of economic power across society. Yet generations of lawyers and judges educated at law schools in the United States have been taught to ignore this essential role of law in creating and sustaining economic power. Instead, we are taught that the social process of economic competition results in certain outcomes that are ‘efficient’ – and that anything the law does to alter those outcomes is its only intervention.

These peculiar presumptions flow from the enormously powerful and influential ‘law and economics’ movement that dominates thinking in most areas of US law considered to be within the ‘economic’ sphere.

More here.

Is Violence Ever Justified? Steven Pinker, Tariq Ali, and Elif Sarican Debate

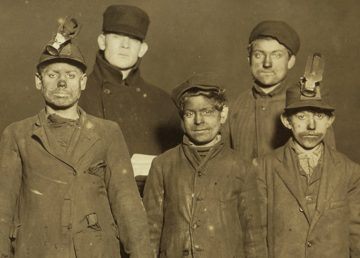

The American Beef Industry and Exploitation

Alicia Kennedy at The Baffler:

Impossible Foods seems to have created heme out of a belief that it’s the visual stimulation of blood oozing from a burger that gives it an addictive taste. What Specht’s book reveals about beef, though, is that its extraordinary success has always had little to do with its taste and everything to do with its ubiquity, increasing cheapness, and cultural status. Red Meat Republic doesn’t bring the reader up to date with innovations in plant-based beef, but it doesn’t have to. By laying down the political and economic history of beef production and culture in the United States, he demonstrates why the tech-meat industry isn’t spending time, money, or marketing dollars on chicken and goat.

Impossible Foods seems to have created heme out of a belief that it’s the visual stimulation of blood oozing from a burger that gives it an addictive taste. What Specht’s book reveals about beef, though, is that its extraordinary success has always had little to do with its taste and everything to do with its ubiquity, increasing cheapness, and cultural status. Red Meat Republic doesn’t bring the reader up to date with innovations in plant-based beef, but it doesn’t have to. By laying down the political and economic history of beef production and culture in the United States, he demonstrates why the tech-meat industry isn’t spending time, money, or marketing dollars on chicken and goat.

Beef is more American than fried chicken, apple pie, and turkey on Thanksgiving. And it has always been political, as Specht chronicles.

more here.

A Portrait of Lebanon

Dominique Eddé at the NYRB:

Beirut—Lebanon is both the center of the world and a dead end. The broken little village of a planet that is sick. Chaotic, polluted, and corrupt beyond belief, this is a country where beauty and human warmth constantly find ways to break through. It is impossible to name that feeling of being assaulted and charmed at the same time. You are in the city center, you stroll down a sidewalk eighteen inches wide, assailed from all sides by the confusion of buildings and traffic, torn between the appeal of the sea and the stench of garbage, and suddenly your gaze is soothed by the play of light on a stone wall, by bougainvilleas cascading from an ancient balcony, by the balcony itself.

You continue on your way, head down. Refugee children’s eyes beg you for something to eat, your impatience gives way to sadness and guilt. You hurry into a shop to buy some reels of yarn, and it’s the beginning of a journey.

more here.

Alice Oswald’s Latest Collection of Poems

Leaf Arbuthnot at the TLS:

Formally, aesthetically, “Tithonus” is a remarkable work. But it is made even more remarkable by its language. Trapped in his decaying body as day knits itself around him, Tithonus notices all. At first, the “bleak shapes of last efforts of / the night”. A little later, “bodiless black lace woods” peopled with songbirds asking one another “is it light is it light”. Later still the “whisper of a grasshopper scraping / back and forth as if working at rust”. The features of dawn concatenate and though Tithonus has seen them all before (and will see them all again), he cannot help but testify to the beauty of breaking day, with its “peach-pale air” and its rustling solitudes. At one point, a lone snail “pokes out of sleep too feelingly / as if a heart had been tinned and / opened”. It is a weird image, ghoulish and frightful, but a moving one.

Formally, aesthetically, “Tithonus” is a remarkable work. But it is made even more remarkable by its language. Trapped in his decaying body as day knits itself around him, Tithonus notices all. At first, the “bleak shapes of last efforts of / the night”. A little later, “bodiless black lace woods” peopled with songbirds asking one another “is it light is it light”. Later still the “whisper of a grasshopper scraping / back and forth as if working at rust”. The features of dawn concatenate and though Tithonus has seen them all before (and will see them all again), he cannot help but testify to the beauty of breaking day, with its “peach-pale air” and its rustling solitudes. At one point, a lone snail “pokes out of sleep too feelingly / as if a heart had been tinned and / opened”. It is a weird image, ghoulish and frightful, but a moving one.

The two major themes that fill the “pipe-work” – in a phrase from the first poem here – of Falling Awake are classical subjects and nature. Without the buttress of a private or grammar school education readers would not necessarily know who Tithonus is or what resonance the River Hebron has (it features in the superb “Severed Head Floating Downriver”, about Orpheus being torn to pieces by Maenads).

more here.

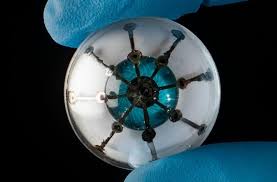

Analytics-enabled, individualized attention will not just treat disease, but increasingly, prevent it

Daniel Kraft in Nautilus:

The innovations I describe here—many of which are still in early stages—are impressive in their own right. But I also appreciate them for enabling the shift away from our traditional compartmentalized health care toward a model of “connected health.” We have the opportunity now to connect the dots—to move beyond institutions delivering episodic and reactive care, primarily after disease has developed, into an era of continuous and proactive care designed to get ahead of disease. Think of it: ever present, analytics-enabled, real-time, individualized attention to our health and well-being. Not just to treat disease, but increasingly, to prevent it.

The innovations I describe here—many of which are still in early stages—are impressive in their own right. But I also appreciate them for enabling the shift away from our traditional compartmentalized health care toward a model of “connected health.” We have the opportunity now to connect the dots—to move beyond institutions delivering episodic and reactive care, primarily after disease has developed, into an era of continuous and proactive care designed to get ahead of disease. Think of it: ever present, analytics-enabled, real-time, individualized attention to our health and well-being. Not just to treat disease, but increasingly, to prevent it.

Just a decade after the first Fitbit launched the “wearables” revolution, health tracking devices are ubiquitous. Most are used to measure and document fitness activities. In the future these sensing technologies will be central to disease prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. They’ll measure health objectively, detect changes that may indicate a developing condition, and relay patients’ data to their clinicians. Flexible, electronic medical tattoos and stick-on sensors can take an electrocardiogram, measure respiratory rate, check blood sugar, and transmit results seamlessly via Bluetooth. It’s mobile vital sign tracking, but at a level once found only in an intensive care unit. Hearing aids or earbuds with embedded sensors will not only amplify sound but also track heart rate and movement. Such smart earpieces also could be integrated with a digital coach to cheer on a runner, or a guide to lend assistance to dementia patients. Smart contact lenses in the future will be packed with thousands of biosensors, and engineered to pick up early indicators of cancer and other conditions. Lenses now in development may someday measure blood sugar values in tears, to help diabetics manage diet and medications.

More here.

Wednesday, June 19, 2019

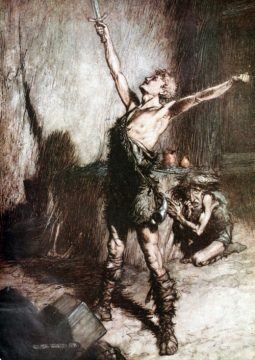

Siegfried’s Bloodline

Antonio Muñoz Molina at The Hudson Review:

Music can have a decisive influence in a person’s life and in a nation’s history. Were it not for a brief passage in the second volume of Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler, I would never have learned of the direct connection between Wagner’s Siegfried and the first crucial victory of Franco’s army during the uprising that set off the Spanish Civil War. On July 25, 1936, as Kershaw recounts, Adolf Hitler attended a production of Siegfried in Bayreuth, which brought him to the state of exaltation that Wagner’s music had always caused in him from early youth. From the age of 17, to be precise, when he first heard Rienzi in Linz—as August Kubizek, friend, countryman and companion during his early years in his native city and then in Vienna, would reverently record years later. On that day in 1906, a young Hitler left the opera house in a fevered state of musical and patriotic excitement, rapt in a sense of kinship with the figure of the Roman tribune who in the fourteenth century tried to revive the glories of imperial Rome, only to meet, in Wagner’s opera, an heroic, glorious end at the hands of his betrayers. In June of 1936, exactly thirty years later, Hitler’s deranged dream was being fulfilled.

Music can have a decisive influence in a person’s life and in a nation’s history. Were it not for a brief passage in the second volume of Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler, I would never have learned of the direct connection between Wagner’s Siegfried and the first crucial victory of Franco’s army during the uprising that set off the Spanish Civil War. On July 25, 1936, as Kershaw recounts, Adolf Hitler attended a production of Siegfried in Bayreuth, which brought him to the state of exaltation that Wagner’s music had always caused in him from early youth. From the age of 17, to be precise, when he first heard Rienzi in Linz—as August Kubizek, friend, countryman and companion during his early years in his native city and then in Vienna, would reverently record years later. On that day in 1906, a young Hitler left the opera house in a fevered state of musical and patriotic excitement, rapt in a sense of kinship with the figure of the Roman tribune who in the fourteenth century tried to revive the glories of imperial Rome, only to meet, in Wagner’s opera, an heroic, glorious end at the hands of his betrayers. In June of 1936, exactly thirty years later, Hitler’s deranged dream was being fulfilled.

more here.

Ten contributors reflect on the continuing relevance — or irrelevance — of postmodernism to the academy and the larger culture

From the Chronicle of Higher Education:

Justin E.H. Smith: All things come to an end, not least the coming-to-an-end of things. And so it had to be with the end of modernism, and the couple of decades of reflection and debate on what was to come next. For me, postmodernism is the copy of Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition, which I bought in English translation in 1993. It’s sitting in a cardboard box, its pages slowly yellowing and its cover design receding into something recognizably vintage, in my old mother’s suburban California garage. I stowed it there when I moved to Paris, in 2013. And in the past six years I have seen only fossil traces of the old beast said to have roamed here in earlier times, eating up grand narratives and truth claims like they were nests full of unprotected eggs.

A few living fossils, coelacanth-like, survived from French philosophy’s âge d’or and could still fill lecture halls. But the survivors were mostly known for their non-representativity, in part because they loudly proclaimed it. Alain Badiou, for example, talked about the transcendental forms of love and beauty. Bruno Latour, not long after 2001, began regretting what his own brand of truth-wariness had done to stoke the “truther” conspiracy theories that had quickly spread to the villagers who worked his family’s vineyards, in Bourgogne.

More here.

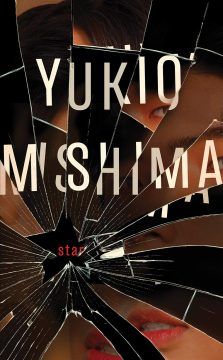

On Yukio Mishima’s “Star”

Jan Wilm at the LARB:

IT SEEMS BOTH the great comedy and the great tragedy of Yukio Mishima’s life that hardly any of his work’s plots live up to his death. While anything but a wallflower, Mishima didn’t have the topsy-turvy life of a Daniel Defoe or a Herman Melville — he was neither jailed and pilloried nor on the hunt for roly-poly whales. But when it comes to spectacular deaths among the writers of the world, Mishima is top tier.

IT SEEMS BOTH the great comedy and the great tragedy of Yukio Mishima’s life that hardly any of his work’s plots live up to his death. While anything but a wallflower, Mishima didn’t have the topsy-turvy life of a Daniel Defoe or a Herman Melville — he was neither jailed and pilloried nor on the hunt for roly-poly whales. But when it comes to spectacular deaths among the writers of the world, Mishima is top tier.

The story goes that he didn’t wait for the ink to dry on his final entry in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy, The Decay of the Angel(published posthumously in 1971), until he made plans for his suicide, in public and full view of the world, when he killed himself after a failed putsch that might never have been wholly political and always a private death masquerading as a public spectacle.

more here.

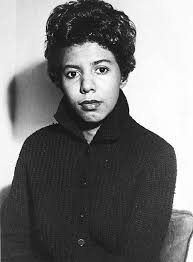

Why We’re Still Looking for Lorraine Hansberry

Daniel A. Jackson at The Point:

When Lorraine Vivian Hansberry died on January 12, 1965, her play The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window was at the end of a three-month run at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre. It was the second play written by a black woman to appear on Broadway. The first was her groundbreaking drama A Raisin in the Sun. Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf, the third, opened in 1976. Remembrances of Shange published last year, after her death, called for colored girls “the second play by an African American woman” to have a Broadway run. In writing my own remembrance of Shange, I nearly made the same mistake. We are prone to myopia when we remember, and it can make inconvenient details difficult to decipher. Jewell Handy Gresham-Nemiroff, in charge of Hansberry’s estate for fourteen years, wrote that Hansberry is “not really credited, to the extent deserved, with being Mother of the modern black drama.” The scholar Margaret Wilkerson called Hansberry one of the “major literary catalysts” of the Black Arts Movement. Both are true, yet The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which Hansberry worked on feverishly during hospital stays at the end of her life, is not a black drama.

When Lorraine Vivian Hansberry died on January 12, 1965, her play The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window was at the end of a three-month run at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre. It was the second play written by a black woman to appear on Broadway. The first was her groundbreaking drama A Raisin in the Sun. Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf, the third, opened in 1976. Remembrances of Shange published last year, after her death, called for colored girls “the second play by an African American woman” to have a Broadway run. In writing my own remembrance of Shange, I nearly made the same mistake. We are prone to myopia when we remember, and it can make inconvenient details difficult to decipher. Jewell Handy Gresham-Nemiroff, in charge of Hansberry’s estate for fourteen years, wrote that Hansberry is “not really credited, to the extent deserved, with being Mother of the modern black drama.” The scholar Margaret Wilkerson called Hansberry one of the “major literary catalysts” of the Black Arts Movement. Both are true, yet The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which Hansberry worked on feverishly during hospital stays at the end of her life, is not a black drama.

more here.

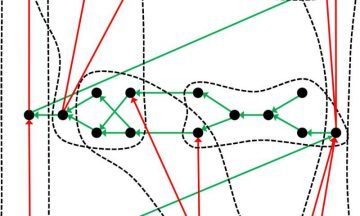

A 53-Year-Old Network Coloring Conjecture Is Disproved

Erica Klarreich in Quanta:

A paper posted online last month has disproved a 53-year-old conjecture about the best way to assign colors to the nodes of a network. The paper shows, in a mere three pages, that there are better ways to color certain networks than many mathematicians had supposed possible.

A paper posted online last month has disproved a 53-year-old conjecture about the best way to assign colors to the nodes of a network. The paper shows, in a mere three pages, that there are better ways to color certain networks than many mathematicians had supposed possible.

Network coloring problems, which were inspired by the question of how to color maps so that adjoining countries are different colors, have been a focus of study among mathematicians for nearly 200 years. The goal is to figure out how to color the nodes of some network (or graph, as mathematicians call them) so that no two connected nodes share the same color. Depending on the context, such a coloring can provide an effective way to seat guests at a wedding, schedule factory tasks for different time slots, or even solve a sudoku puzzle.

Graph coloring problems tend to be simple to state, but they are often enormously hard to solve. Even the question that launched the field — Do four colors suffice to color any map? — took more than a century to answer (the answer is yes, in case you were wondering).

More here.

What Orville Wright can teach us about solving our clean energy problem

William Budinger in Democracy:

Thinking about the risk-reward of air travel can help us think about how to solve the most perplexing problem of our time—the clean energy dilemma. All the known solutions to producing clean power have risks. So how do we evaluate the risk/reward of each possibility? How do we decide which ones to pursue? Being human, our evaluation of risk is hampered by our tendency to focus on the sensational single event instead of the broader picture. When looking at accidents or “disasters,” we also tend to ignore the reward we were getting from whatever it was that failed. For example, if one were to focus only on crashes, deaths, and disasters, we would quickly conclude that air travel is deadly and must be seriously curtailed. Yet in spite of the danger, people clearly think the reward of air travel is worth taking the risk. Moreover, if one steps back, looks at the full picture, and evaluates the danger of air travel compared to other methods, it becomes clear that putting a halt to air travel would result in more, not fewer, deaths. The relative risk of air travel is lower than other travel options.

Thinking about the risk-reward of air travel can help us think about how to solve the most perplexing problem of our time—the clean energy dilemma. All the known solutions to producing clean power have risks. So how do we evaluate the risk/reward of each possibility? How do we decide which ones to pursue? Being human, our evaluation of risk is hampered by our tendency to focus on the sensational single event instead of the broader picture. When looking at accidents or “disasters,” we also tend to ignore the reward we were getting from whatever it was that failed. For example, if one were to focus only on crashes, deaths, and disasters, we would quickly conclude that air travel is deadly and must be seriously curtailed. Yet in spite of the danger, people clearly think the reward of air travel is worth taking the risk. Moreover, if one steps back, looks at the full picture, and evaluates the danger of air travel compared to other methods, it becomes clear that putting a halt to air travel would result in more, not fewer, deaths. The relative risk of air travel is lower than other travel options.

The various options available to clean up our energy emissions must be similarly evaluated. In terms of risk, any and all of the commonly available options for generating clean electricity are much less dangerous than the climate disaster we’ll face if we fail to reverse global warming. To effectively tackle climate change, all serious experts agree that we must get as close to zero carbon as possible, and do so as quickly as possible. So our selection standard should be which technologies, when considered in view of their rewards, will get us there fastest with no more risk than is manageable. The good news is that all of the available low-carbon options—all of them—have risk levels much lower than those we tolerate daily with our existing fossil plants, chemical plants, refineries, and even airplanes.

More here.