Damian Carrington in The Guardian:

The world is increasingly at risk of “climate apartheid”, where the rich pay to escape heat and hunger caused by the escalating climate crisis while the rest of the world suffers, a report from a UN human rights expert has said.

The world is increasingly at risk of “climate apartheid”, where the rich pay to escape heat and hunger caused by the escalating climate crisis while the rest of the world suffers, a report from a UN human rights expert has said.

Philip Alston, UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, said the impacts of global heating are likely to undermine not only basic rights to life, water, food, and housing for hundreds of millions of people, but also democracy and the rule of law.

Alston is critical of the “patently inadequate” steps taken by the UN itself, countries, NGOs and businesses, saying they are “entirely disproportionate to the urgency and magnitude of the threat”. His report to the UN human rights council (HRC) concludes: “Human rights might not survive the coming upheaval.”

The report also condemns Donald Trump for “actively silencing” climate science, and criticises the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, for promising to open up the Amazon rainforest to mining.

More here.

Placed together, the book’s two longest chapters, “Big Bad Science” and “The Medical Misinformation Mess”, lay out the charge sheet against modern scientific research in medicine. Medical research, particularly “Big Science” or “Big Data”, has always promised far more than it has delivered, and Big Science has in fact contributed little to medical advances; research and clinical trials, meanwhile, are in the midst of a “replication crisis”, where a huge percentage of trials either never are or cannot be replicated. The first issue medical research must face if it is to reform is “that the culture of contemporary medical research is so conformist that truly original thinkers can no longer prosper in such an environment, and that science selects for perseverance and sociability at the expense of intelligence and creativity”. O’Mahony quotes Bruce Charlton: “[the requirements of contemporary research are] enough to deter almost anyone with a spark of vitality or self-respect … Modern science is just too dull an activity to attract, retain or promote many of the most intelligent and creative people”. “Real scientists,” says O’Mahony, “tend to be reticent, self-effacing, publicity-shy and full of doubt and uncertainty, unlike the gurning hucksters who seem to infest medical research.”

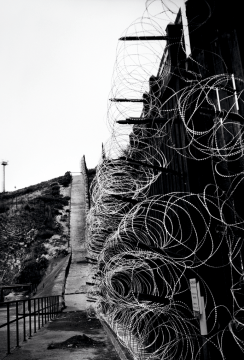

Placed together, the book’s two longest chapters, “Big Bad Science” and “The Medical Misinformation Mess”, lay out the charge sheet against modern scientific research in medicine. Medical research, particularly “Big Science” or “Big Data”, has always promised far more than it has delivered, and Big Science has in fact contributed little to medical advances; research and clinical trials, meanwhile, are in the midst of a “replication crisis”, where a huge percentage of trials either never are or cannot be replicated. The first issue medical research must face if it is to reform is “that the culture of contemporary medical research is so conformist that truly original thinkers can no longer prosper in such an environment, and that science selects for perseverance and sociability at the expense of intelligence and creativity”. O’Mahony quotes Bruce Charlton: “[the requirements of contemporary research are] enough to deter almost anyone with a spark of vitality or self-respect … Modern science is just too dull an activity to attract, retain or promote many of the most intelligent and creative people”. “Real scientists,” says O’Mahony, “tend to be reticent, self-effacing, publicity-shy and full of doubt and uncertainty, unlike the gurning hucksters who seem to infest medical research.” Let us now meet the migrants themselves. We begin with one quietly cheerful shelter for asylum seekers. Although the Methodists had started it, “We have Unitarians, we have Catholics, we have Presbyterians, Lutherans, and some people who are atheists. I even have a couple of Republicans helping out! They talk to me about the wall but are still here helping out.” In keeping with the regional mood, I was asked not to identify the place (“in the Tucson foothills”), and the co-coordinator who showed me around (she was called Diane) declined to provide her last name, because “we’re just kinda protecting our folks. We don’t want location or names or anything like that, because I worry about protesters.” No location, then, but I will say that planted in the gravel in front of the building stood a sign from that brave organization No More Deaths: humanitarian aid is never a crime—drop the charges, with a hand reaching up for a water jug somewhere between two saguaro cacti.

Let us now meet the migrants themselves. We begin with one quietly cheerful shelter for asylum seekers. Although the Methodists had started it, “We have Unitarians, we have Catholics, we have Presbyterians, Lutherans, and some people who are atheists. I even have a couple of Republicans helping out! They talk to me about the wall but are still here helping out.” In keeping with the regional mood, I was asked not to identify the place (“in the Tucson foothills”), and the co-coordinator who showed me around (she was called Diane) declined to provide her last name, because “we’re just kinda protecting our folks. We don’t want location or names or anything like that, because I worry about protesters.” No location, then, but I will say that planted in the gravel in front of the building stood a sign from that brave organization No More Deaths: humanitarian aid is never a crime—drop the charges, with a hand reaching up for a water jug somewhere between two saguaro cacti. Caradec’s Dictionary, newly translated into English by Chris Clarke, lists some 850 gestures that “successively address each part of the body, from top to bottom, from scalp to toe by way of the upper limbs”, and may be used as well as or instead of speech. They are numbered and ordered in a taxonomy running from 1.01 (“to nod one’s head vertically up and down, back to front, one or several times: acquiescence”) to 37.12 (“to kick an adversary in the rear end: aggression”), and accompanied by Philippe Cousin’s illustrations. The majority of them are what the psychologist David McNeill has called “imagistic”, by which parts of the body are arranged to figure an imagined object or action (such as blowing a kiss, or proffering one’s middle finger), and are “effected voluntarily by humankind in order to communicate with each other”. The emphasis designates this type of non-verbal expression – Adam Kendon calls it “visible action as utterance” in his seminal Gesture (2004) – as a sub-category of body language more broadly, which comprises both conscious (that is, learnt) and unconscious (instinctive) movements.

Caradec’s Dictionary, newly translated into English by Chris Clarke, lists some 850 gestures that “successively address each part of the body, from top to bottom, from scalp to toe by way of the upper limbs”, and may be used as well as or instead of speech. They are numbered and ordered in a taxonomy running from 1.01 (“to nod one’s head vertically up and down, back to front, one or several times: acquiescence”) to 37.12 (“to kick an adversary in the rear end: aggression”), and accompanied by Philippe Cousin’s illustrations. The majority of them are what the psychologist David McNeill has called “imagistic”, by which parts of the body are arranged to figure an imagined object or action (such as blowing a kiss, or proffering one’s middle finger), and are “effected voluntarily by humankind in order to communicate with each other”. The emphasis designates this type of non-verbal expression – Adam Kendon calls it “visible action as utterance” in his seminal Gesture (2004) – as a sub-category of body language more broadly, which comprises both conscious (that is, learnt) and unconscious (instinctive) movements. Sameer Rahim’s debut novel is a tender, pin-sharp portrait of a marriage and a community. It is a wonderful achievement; an invigorating reminder of the power fiction has to challenge lazy stereotypes, and stretch the reader’s heart. Asghar Dhalani and Zahra Amir are young west Londoners, from a tight-knit but fractious east African Muslim community. They have known each other since childhood, but their families have very different approaches to the challenge of making a life in England. The Amirs pride themselves on their refinement and open-mindedness – Zahra left home to study at Cambridge, and is fond of saying things like, “it’s textbook Orientalism, Mummy”. The Dhalanis are “the most traditional of the traditional”; 19-year-old Asghar won’t eat a cheese sandwich until he’s checked it’s halal. Everyone, not least Asghar, is surprised when Zahra accepts his proposal.

Sameer Rahim’s debut novel is a tender, pin-sharp portrait of a marriage and a community. It is a wonderful achievement; an invigorating reminder of the power fiction has to challenge lazy stereotypes, and stretch the reader’s heart. Asghar Dhalani and Zahra Amir are young west Londoners, from a tight-knit but fractious east African Muslim community. They have known each other since childhood, but their families have very different approaches to the challenge of making a life in England. The Amirs pride themselves on their refinement and open-mindedness – Zahra left home to study at Cambridge, and is fond of saying things like, “it’s textbook Orientalism, Mummy”. The Dhalanis are “the most traditional of the traditional”; 19-year-old Asghar won’t eat a cheese sandwich until he’s checked it’s halal. Everyone, not least Asghar, is surprised when Zahra accepts his proposal. As scientists record from an

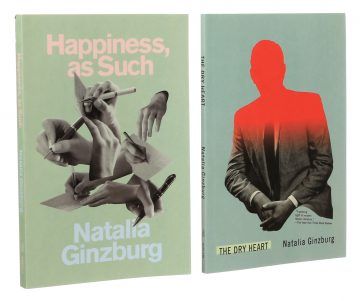

As scientists record from an  The voice is instantly, almost violently recognizable — aloof, amused and melancholy. The metaphors are sparse and ordinary; the language plain, but every word load-bearing. Short sentences detonate into scenes of shocking cruelty. Even in middling translations, it is a style that cannot be subsumed; Natalia Ginzburg can only sound like herself.

The voice is instantly, almost violently recognizable — aloof, amused and melancholy. The metaphors are sparse and ordinary; the language plain, but every word load-bearing. Short sentences detonate into scenes of shocking cruelty. Even in middling translations, it is a style that cannot be subsumed; Natalia Ginzburg can only sound like herself. When the last of a species disappears, it usually does so unnoticed, somewhere in the wild. Only later, when repeated searches come up empty, will researchers reluctantly acknowledge that the species must be extinct. But in rare cases like George’s, when people are caring for an animal’s last known representative, extinction—an often abstract concept—becomes painfully concrete. It happens on their watch, in real time. It leaves behind a body. When Sischo rang in the new year, Achatinella apexfulva existed. A day later, it did not. “It is happening right in front of our eyes,” he said.

When the last of a species disappears, it usually does so unnoticed, somewhere in the wild. Only later, when repeated searches come up empty, will researchers reluctantly acknowledge that the species must be extinct. But in rare cases like George’s, when people are caring for an animal’s last known representative, extinction—an often abstract concept—becomes painfully concrete. It happens on their watch, in real time. It leaves behind a body. When Sischo rang in the new year, Achatinella apexfulva existed. A day later, it did not. “It is happening right in front of our eyes,” he said. Human beings are the type of animal that depend upon the diversity and plenitude of other life to sustain us. It’s no coincidence that our presence arrived concomitant with the richest biota the earth has ever developed. This wealth of life created the complex and flexible niche that we’ve come to fill, not only passively, as our food source, but even actively, as symbionts living on our skin and

Human beings are the type of animal that depend upon the diversity and plenitude of other life to sustain us. It’s no coincidence that our presence arrived concomitant with the richest biota the earth has ever developed. This wealth of life created the complex and flexible niche that we’ve come to fill, not only passively, as our food source, but even actively, as symbionts living on our skin and  P

P Liu’s tomes—they tend to be tomes—have been translated into more than twenty languages, and the trilogy has sold some eight million copies worldwide. He has won China’s highest honor for science-fiction writing, the Galaxy Award, nine times, and in 2015 he became the first Asian writer to win the Hugo Award, the most prestigious international science-fiction prize. In China, one of his stories has been a set text in the gao kao—the notoriously competitive college-entrance exams that determine the fate of ten million pupils annually; another has appeared in the national seventh-grade-curriculum textbook. When a reporter recently challenged Liu to answer the middle-school questions about the “meaning” and the “central themes” of his story, he didn’t get a single one right. “I’m a writer,” he told me, with a shrug. “I don’t begin with some conceit in mind. I’m just trying to tell a good story.”

Liu’s tomes—they tend to be tomes—have been translated into more than twenty languages, and the trilogy has sold some eight million copies worldwide. He has won China’s highest honor for science-fiction writing, the Galaxy Award, nine times, and in 2015 he became the first Asian writer to win the Hugo Award, the most prestigious international science-fiction prize. In China, one of his stories has been a set text in the gao kao—the notoriously competitive college-entrance exams that determine the fate of ten million pupils annually; another has appeared in the national seventh-grade-curriculum textbook. When a reporter recently challenged Liu to answer the middle-school questions about the “meaning” and the “central themes” of his story, he didn’t get a single one right. “I’m a writer,” he told me, with a shrug. “I don’t begin with some conceit in mind. I’m just trying to tell a good story.” I first came across the work of Nabarun Bhattacharya (1948–2014) about a decade ago in Calcutta, after a long afternoon of wandering conversation of the kind that Bengalis call adda, a session that no doubt included numerous cups of tea, many cigarettes, much talk about books, films, and politics before peaking, in the evening, with kebabs and cheap Indian rum. These freewheeling hours of aimless mental flaneurie that make no concessions to modernity’s iron cage of productivity and self-improvement have their own usefulness. Somewhere in the course of that day, from the recommendations of my companions, I ended up buying a copy of Harbart.

I first came across the work of Nabarun Bhattacharya (1948–2014) about a decade ago in Calcutta, after a long afternoon of wandering conversation of the kind that Bengalis call adda, a session that no doubt included numerous cups of tea, many cigarettes, much talk about books, films, and politics before peaking, in the evening, with kebabs and cheap Indian rum. These freewheeling hours of aimless mental flaneurie that make no concessions to modernity’s iron cage of productivity and self-improvement have their own usefulness. Somewhere in the course of that day, from the recommendations of my companions, I ended up buying a copy of Harbart.

How do we structure our moving, changing thoughts and how do we structure the world we design and move and act in?

How do we structure our moving, changing thoughts and how do we structure the world we design and move and act in? As animals explore their environment, they learn to master it. By discovering what sounds tend to precede predatorial attack, for example, or what smells predict dinner, they develop a kind of biological clairvoyance—a way to anticipate what’s coming next, based on what has already transpired. Now, Rockefeller scientists have found that an animal’s education relies not only on what experiences it acquires, but also on when it acquires them. Studying

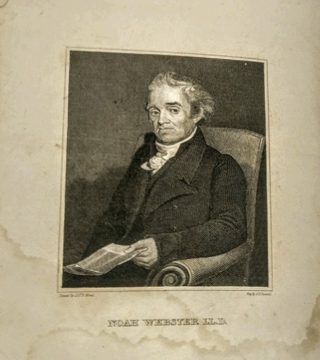

As animals explore their environment, they learn to master it. By discovering what sounds tend to precede predatorial attack, for example, or what smells predict dinner, they develop a kind of biological clairvoyance—a way to anticipate what’s coming next, based on what has already transpired. Now, Rockefeller scientists have found that an animal’s education relies not only on what experiences it acquires, but also on when it acquires them. Studying  In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.

In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.